Retirement is for wimps

Japan's willing elderly workers are defusing the country's pension time bomb, writes Kanoko Matsuyama

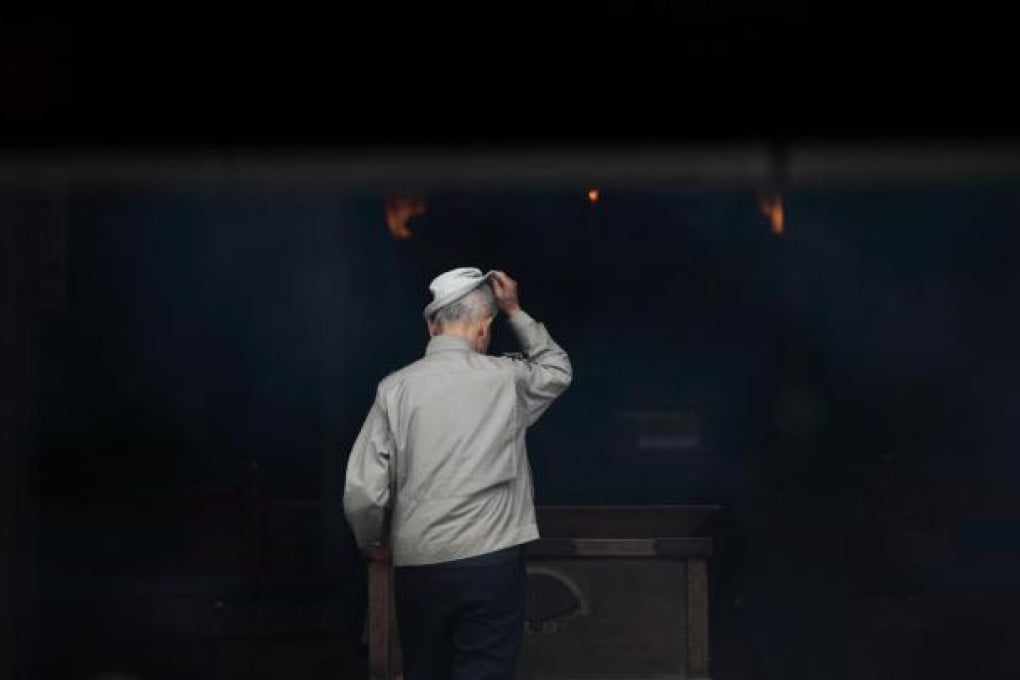

The thought of retiring after more than four decades made Hirofumi Mishima anxious. Instead of looking forward to ending his three-hour daily commute, Mishima wanted to work, even if it meant another hour on the train.

"Keeping a regular job is the most stimulating thing for me," says Mishima, 69, who spent six months trawling the vacancy boards at a Tokyo employment centre after retiring from his US$77,000-a-year job as an industrial gas analyst in 2009. "If I was at home all day, I'd get out of shape and my wife would fret about all the extra chores she'd have to do."

Mishima is one of 5.7 million Japanese older than 65 still in the workforce for money, health or to seek friends - the highest proportion of employed seniors in the developed world. While European governments struggle to convince their voters to sign up for longer work lives, Japan faces the opposite issue: how to meet the wishes of an army of willing elderly workers.

Japan's lower house passed legislation this month that would give private sector employees the right to keep working for another five years, up to 65. With the world's longest life expectancy, largest public debt and below-replacement birth rate, curbing spiralling welfare costs by keeping people in jobs longer may help defuse a pension time bomb that threatens to overturn or bankrupt governments in the developed world.

"The raising of the retirement age, it's a good thing, and more importantly, we have no alternatives," said Michael Hodin, a researcher at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York specialising in health policies and ageing populations. Current concepts of retirement don't make sense in the context of 21st-century demographics, and governments are looking to reframe the social contract, he said.