Hong Kong's darkest hour: Sars and the suicide of an icon

In April 2003, Hong Kong was reeling from disease, war and the death of actor and singer Leslie Cheung. The fallout from these events changed the SAR forever, perhaps even more than the handover six years previously

One August morning in 2000, a Hong Kong boy called Yu Man-hon ran away from his mother at Yau Ma Tei MTR station, travelled up to Lo Wu and darted across the border. He was 15 but autistic; his mental age was that of a two-year-old.

The authorities on the Shenzhen side caught him and returned him to Hong Kong, where he was questioned by immigration officials. Man-hon cried, threw food around, urinated, couldn't speak coherently. Assuming that he was a peasant mainlander, the Hong Kong officials sent him back across the border. In those days, you could do that; three years after the handover, the special administrative region was determined to keep itself inviolate, a state within a state.

Man-hon's mother began searching for him in Guangdong. I interviewed her that Christmas in her Lok Fu flat, and the following spring I spent a few days with her at the Railway Station Hotel in Shenzhen, where she'd based herself. Every day, she handed out hundreds of her son's photographs to passers-by and dealt with the endless phone calls (begging, blackmailing, abusive) that resulted. She'd told me she wouldn't stop until she found out what had happened to her son and she kept looking, commuting back and forwards across the border, until early in 2003.

She didn't tell me this until months later, when it was over, but I often think of her fearful expectancy while the rest of us continued in ignorance of what was going to happen. And what happened, initially, was – nothing. February 2003 was a month when two superpowers simultaneously played propaganda games with the rest of the world. The United States insisted there was a global threat where none existed; and China did the opposite. On February 6, Colin Powell, then US secretary of state, told the United Nations in New York "the facts, and Iraq's behaviour, show that Saddam Hussein and his regime are concealing their efforts to produce more weapons of mass destruction".

On February 11, Dr Yeoh Eng-kiong, Hong Kong's secretary for health, welfare and food, who'd been asked by a reporter the previous day about a problem the mainland seemed to be having with pneumonia, said, "We have been in contact with the Ministry of Health in China and we understand that there have been about 300 cases of which there are five fatalities. But many of the infections have been mild and there is no need for people to worry and panic."

The point about that Hong Kong spring a decade ago, that near-apocalyptic season of war and disease, is you couldn't believe a word uttered by anyone in authority.

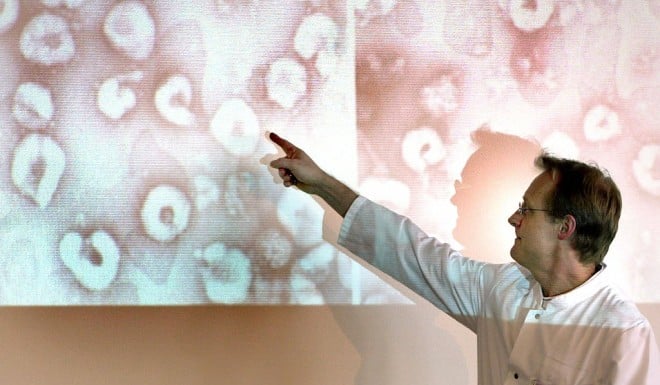

Occasionally, in the intervening years, I've heard doctors complain that the media got it out of proportion. But when medical workers began falling sick in Sha Tin's Prince of Wales Hospital at the end of the first week of March, it was doctors who forecast dire consequences. Two of them gave vivid warnings on the same day in the . One was Dr David Anderson's letter recommending the immediate cancellation of the Rugby Sevens (which went ahead without incident) and the other was a front-page interview with Professor Sydney Chung Sheung-chee, dean of medicine at Chinese University, in which he said of Sars, "It is a holocaust. It is a war with an unknown enemy. My hands have shaken for two nights. It is the worst medical disaster I have ever seen."

We were about to disappear into a muffled, sanitised world. My Kennedy Town flat was (and still is) rented from the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, and it proved useful to have a medical landlord, with plague in the offing. While the Hong Kong government procrastinated, Tung Wah introduced a swabbing protocol in which the building's common areas were disinfected every three hours. A cleaning lady moved into the lifts: for weeks, I literally never saw her do anything else except tend to their surfaces. She was a pioneer. Soon every lift, every ATM machine, every keypad into Hong Kong buildings would be sheathed in plastic; it would be months before we'd touch naked buttons again.

Does it sound ridiculous to say that, until the end of March, none of it felt real? When the government tardily announced new measures under the Quarantine and Prevention of Disease Ordinance, when people started to flee, when – exactly 10 years ago today – there was a residents' round-up raid on Amoy Gardens, as sensationally directed as a B-movie, it still had the flavour of make-believe. The advance on Baghdad was dominating the news and if America was putting on an apparently polished performance in its theatre of war, we were an uncertain drama bumbling about in the wings.

Then April began, and the phoney war ended. On April 1, the US government issued a directive authorising the paid departure of non-emergency employees from the consulate here – not quite helicopters on a roof in Saigon but not an encouraging message to the local populace. On the same day, a 14-year-old schoolboy placed an announcement, under 's masthead, on his website. It said that Hong Kong had been declared an infected port, the airport was closing, the Hang Seng Index had collapsed and chief executive Tung Chee-hwa had resigned. People panicked. The police had to be called when fights broke out in packed shops between customers grabbing rice, bleach, cooking oil; the supermarkets had to spend all night restocking; the government had to hold an emergency press conference.

And when – having nipped out to buy milk, seen the crowds, given up baffled, returned home, slipped on a disinfected corridor, wondered if bleach would kill me quicker than Sars – on the evening of that chaotic day, I heard Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing had killed himself, I thought that was the April Fool's Day prank. I wasn't a particular fan, I'd only seen a few of his films, but his death, the manner of it amidst the mounting mortality statistics, was a lightning conductor for the city's fear. (I remember thinking, illogically but insistently: did he know something? And weeks later, sitting in a taxi while the masked driver swore furiously at the mention of Cheung's name, and asked how he could have done that to us, I knew what he meant.)

The following day, April 2, the World Health Organisation (WHO) issued its travel advisory; and everything went into freefall.

At the end of the first week of April, I went over to Tsim Sha Tsui to say goodbye to an American friend in the hotel industry who'd been told, like many others, to take extended leave. By then, airline crews were refusing to stay here overnight, flights were being suspended and tourism had ceased to exist. Expats – especially wives and children – were returning to their own countries. Some of them never came back (and one of them, Nancy Kissel, would return reluctantly, having had an affair, and murder her husband).

I'd been in Hong Kong for exactly 10 years and it had been considerably kinder to me than Northern Ireland, where I'd spent a decade of childhood. I still measured threat on an irrational scale that found an unattended bag, or an erratically parked car, more scary than an invisible virus. But I hadn't realised how much I'd rooted in this city until I was urged to leave it. ("Though it's easy for you," friends said, taking what they thought might be the last planes out, "you don't have children.")

On the Star Ferry, that Sunday night, the spring fog hung so low you could hardly see Hong Kong Island. Anything could be incubating in such a shroud. I walked to Cheung's memorial, which had sprung up at the Mandarin Oriental hotel, near the spot where he'd plummeted to earth from the 24th floor. There were so many white flowers it was as if a bank of snow had been swept against a corner of Ice House Street. , read the notes on the pale bouquets: Big Brother.

Mourners stood in clusters by the almost-empty hotel. Behind their damp face masks, I knew they were crying but they weren't uttering a sound, and such frozen silence was so alien within Hong Kong's landscape, it tore at the heart like a scythe. I thought, "What will become of us?" , as any Western expat knows, is supposed to mean "ghost man". But we were all ghosts now, and we were all in this together.

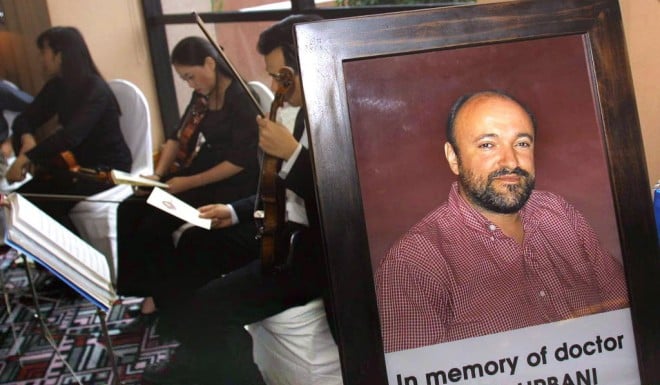

When Carlo Urbani of the WHO called the new disease (which would soon kill him) severe acute respiratory syndrome, the SAR administration asked that it be renamed. It seemed an unfair coincidence that Hong Kong should be linguistically, as well as geographically, linked with an illness for which it wasn't responsible. Atypical pneumonia, the government's English-language press releases firmly called it; but Sars and the SAR were forever co-joined.

It lasted 100 days. "My dearest imprisoned daughter," my mother wrote to me, when other countries started banning Hong Kong residents from entry (for it turned out that we, not Saddam, were the biological hazard), and she enclosed a cure from Ireland – specially blessed salt someone had sourced in Sars-free Donegal. It was no dafter than the many other remedies of that time. I kept a file of them, including a photograph of a man in Beijing who strolled about carrying a large picture of Chairman Mao as a prophylactic.

And I re-read Daniel Defoe's published in 1722, and set in 1665 London. In 2003 Hong Kong it wasn't some fusty literary classic, it was a prediction of tomorrow's headlines. The use of vinegar, the deaths of doctors, the shutting up of houses, the departure of the wealthy, the orders for cleansing the streets: it was all there.

In Defoe's London, bills of mortality were posted to keep people informed of the tally of dead in each parish. In Hong Kong, the government issued the daily numbers of dead and infected and, later, the buildings where those who'd contracted Sars lived. I'd listen to those lists, late at night, on RTHK, in between the triumphant reports from Mosul, Tikrit, Ramadi. There had been a "hot war" in 1665, too, the English against the Dutch; and it, too, had been a second war, a continuation of an earlier, unresolved one.

Defoe hadn't known how plague was transmitted. That global mystery would be solved in a bamboo shed, in Kennedy Town, by a Swiss man called Alexandre Yersin during a plague outbreak in 1894 that killed 2,500 people.

As the weather grew warmer, I used to walk around Kennedy Town, with its street names that could have come from 17th-century London (Smithfield, Cadogan, Belcher's), and along Kennedy Town Praya, where everyone came out after dusk to breathe the sea air - salty as a Donegal cure - through their masks. And I'd marvel at the repetition of history and at the stoicism of human nature and our ability to adapt.

In the end, like the London plague, Sars went away. It was a coronavirus, a virus shaped like a crown, that began its reign in a hospital named after a British prince; and was like the final gasp of the colonial era. Every day of that spring, I'd looked at the front pages of the newspapers, English and Chinese, in which the World Health Organisation was constantly quoted, and what I saw was a single word in capitals: WHO, WHO, WHO, like someone shouting a question about identity. It seemed Sars was the story overseas journalists had expected to write back in 1997, when they were half-hoping newsworthy death would cross the Chinese border. Sars was when the handover really took place.

Southern China has a tradition of double burial, which is still observed in Hong Kong. There's the temporary flesh-burial in the earth; then, after six years, there's the disinterment, the scraping off of flesh and the repackaging of the bones. Six years after the clamour and ballyhoo of 1997, we were permanently placed in our niche within China. The PRC's stringent restrictions on its citizens travelling here were lifted because no one else would come; and the repercussions of that have changed Hong Kong far more than the actual sickness itself.

Man-hon was never found. I often think of him, the Hong Kong boy swallowed up by the mainland when Hong Kong was determined to keep the mainland at bay.

It seems a long time ago.