Drawing ire

When freedom of expression is repressed, a picture can say a lot more than a thousand words. Chris Luo speaks with some mainland cartoonists who are going online to get their message across to a vast and ever more enlightened audience

One of the first things political cartoonist Wang Liming did last month after being released from almost 20 hours of detention and questioning by Beijing police was to post a message online to his followers. "I am out," he wrote on mainland microblogging site Sina Weibo, before thanking his 300,000 fans for their support. "I have seen and heard many interesting things in the police station overnight," he continued, promising to share his experiences.

Within 24 hours, Wang had posted a series of pencil sketches that showed in detail how he had been questioned for "spreading rumours online and stirring trouble". His drawings depicted the cushioned walls and uncomfortable steel chair in the police interrogation room; the small, spartan cell in which he spent the night; his fear of being sexually molested by other inmates; and an SMS conversation a chatty policeman had shown him of an argument with his wife, who was threatening to divorce him for never being at home.

Fortunately, Wang told his followers, the police let him go with just a warning for reposting unverified messages on social media about unreported deaths of flood victims in typhoon-hit Zhejiang province.

This was not Wang's first brush with the law. He told Post Magazine in a telephone interview just three days before his latest detention that he had been "invited to tea" - a common euphemism for being detained, warned or threatened by the police or state security agents - on several occasions for his defiant speech and online artwork.

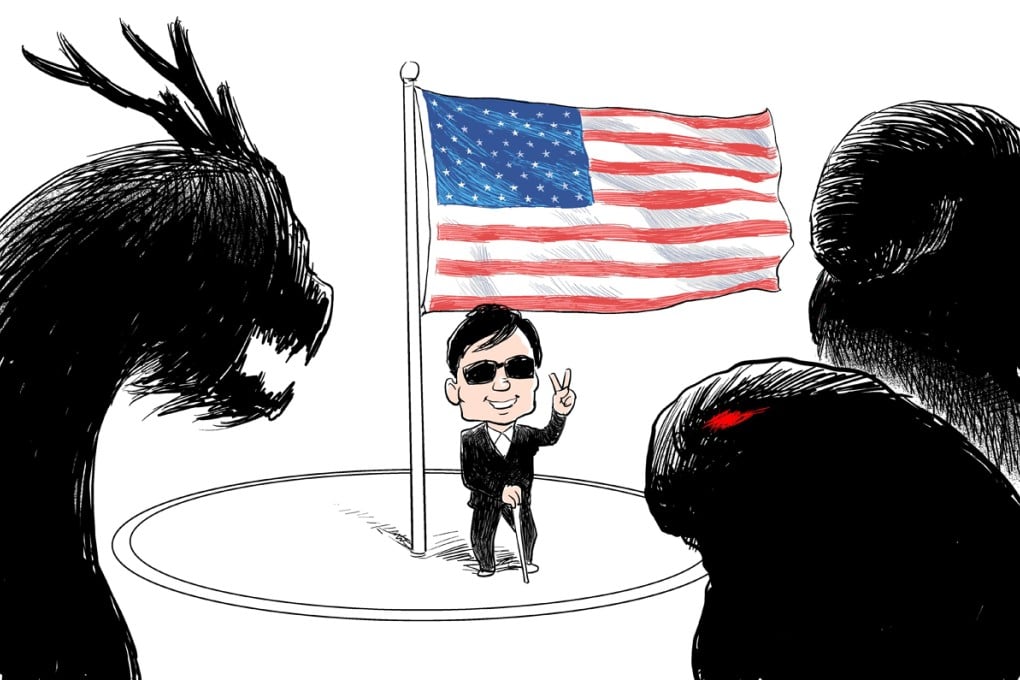

Better known by the alias "Rebel Pepper" and for his signature self-portrait - a flamboyant red chilli pepper with a sarcastic smile - 40-year-old Wang is a leading figure among an emerging group of political cartoonists who have established their voices and found increasing popularity on the mainland's social media networks, despite an intensifying campaign launched by the government this year to suppress dissent in cyberspace.

"They [the police] tried very hard to find out if my unruly comments online were propelled by a certain overseas anti-China force," Wang says. "But the expressions were made only out of my impulse to comment on current affairs."