Mainland censorship: authors cut their losses

When writing about China for a mainland readership, overseas authors face a dilemma: appease the censors or refuse to publish. Dinah Gardner talks to writers who have had to make that choice

Next to the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Tibet, is the city's main post office. Buried under postcards of yaks, tacky tourist maps, guidebooks and Buddhist paperbacks in the post office's dusty and tumbledown bookshop is a copy of , the autobiography of Tashi Tsering. The Tibetan nationalist lived through the cruelties of pre-1950 Tibet and the madness and injustices of the Cultural Revolution. He spent six years in a Chinese jail accused of being a counter-revolutionary.

The book is a Chinese translation of , first published in the United States in 1997. Not only is it extraordinary that a Chinese version was published at all - Tibet ranks top in terms of sensitive topics in the mainland - it also seems remarkable that such a politically charged book should turn up here, in Lhasa, one of China's most tense and heavily policed cities.

Remarkable, that is, until you realise that the version released by the China Tibetology Publishing House was carefully censored. According to a study at Columbia University, in the US, a number of changes were made, the most notable being the deletion of Tashi Tsering's meetings with the 14th Dalai Lama.

Since 2006, when came out, the mainland market for translated works has been growing steadily. In 2010, the mainland's 580 state-owned publishers (the only ones permitted to publish and distribute books nationally) acquired 13,724 titles from abroad, according to the organisers of the Frankfurt Book Fair. Two years later, Harry Potter creator J.K. Rowling earned US$2.4 million for her simplified Chinese version of , making her royalties the fourth largest in the country in 2012, reported the .

However - and this is especially true for books about China - authors must be able to stomach the obligatory censorship if they are to be published in the mainland. While the attractions of the Chinese market - more money and the chance to engage with a new readership - grow, the costs to a writer's reputation and to the truth may turn out to be far greater than the rewards.

The cuts would have not only distorted his narrative about the country, Osnos says, but they would also have betrayed the very people he was writing about - people who are trying to make China a better place.

"Chinese citizens such as the filmmaker Feng Xiaogang are speaking publicly about the problem of censorship," Osnos tells . "I felt that the least I can do is not make a choice that undermines those efforts by pretending censorship is not a problem."

Last year, Feng made an impassioned speech against censorship as he was accepting an award in Beijing. The televised event censored out the word "censorship".

"I have a responsibility to ensure that Chinese readers are not given an altered view of the events I described," says Osnos. "Chinese readers want to know what the world thinks about their country's extraordinary rise - that's why they buy these books - and we, as writers, have a responsibility to offer an answer."

Osnos' principled stand has earned him support from Western writers on China, commentators and even both editors and readers in the mainland. They see censorship as an insult to the author and the people being written about; at best it gives a distorted picture of the truth and, at worst, credence to official falsehoods and propaganda.

A Shanghai-based book editor, who wishes to remain anonymous, says, "A censored version absolutely hurts the integrity of a work, and violates the right to a free press. As an editor, I'm supposed to prejudge how much of the content will be cut and how much will be kept. If the censorship hurts the integrity badly, I will give up the project."

Chen Chunhua, a Chinese graduate student of political science now living in the US, says she reads Western books about China because she wants a "new perspective" on her country. Osnos made the right decision not to publish, she says, because "what makes the book worth reading would be exactly that censored 25 per cent".

Censorship "contributes to this persistent non-stop tweaking of recorded reality that happens in China", says Jeremy Goldkorn, a South African based in Beijing, who founded media research company Danwei. "It contributes to China's ongoing incomprehension of how the rest of the world looks at them. I think that is a harmful thing for China in the long run."

While it is no secret to the Chinese readership that books are censored, it is not always clear where excisions have been made. Uncensored versions are often published in Taiwan and Hong Kong and these are available unofficially in the mainland from websites such as Taobao, but the numbers sold this way are relatively small.

"The black market in books is tolerated, but the moment someone started publishing books with sensitive content, that tolerance would likely evaporate," says Eric Abrahamsen, an American publishing consultant and literary translator based in Beijing.

Some enthusiasts post breakdowns on the internet of what has been censored from mainland editions but, again, few people are likely to be accessing these sites.

"Websites highlighting mainland censorship would have small readerships, otherwise they would get censored themselves," says Goldkorn.

When Ezra F. Vogel, professor emeritus at Harvard University, in the US, published a censored mainland version of his last year, he told , "I thought it was better to have 90 per cent of the book available here than zero." He defended his decision on the Harvard University Press website, saying it was the first time a book had been published in the mainland that talked about the Tiananmen Square incident and "many Chinese academics were appreciative that my book had expanded the range of freedom, allowing them to discuss more topics than had been possible before the book was published".

But Vogel's book is a record of history and accepting those cuts, some argue, turned his book into a lie.

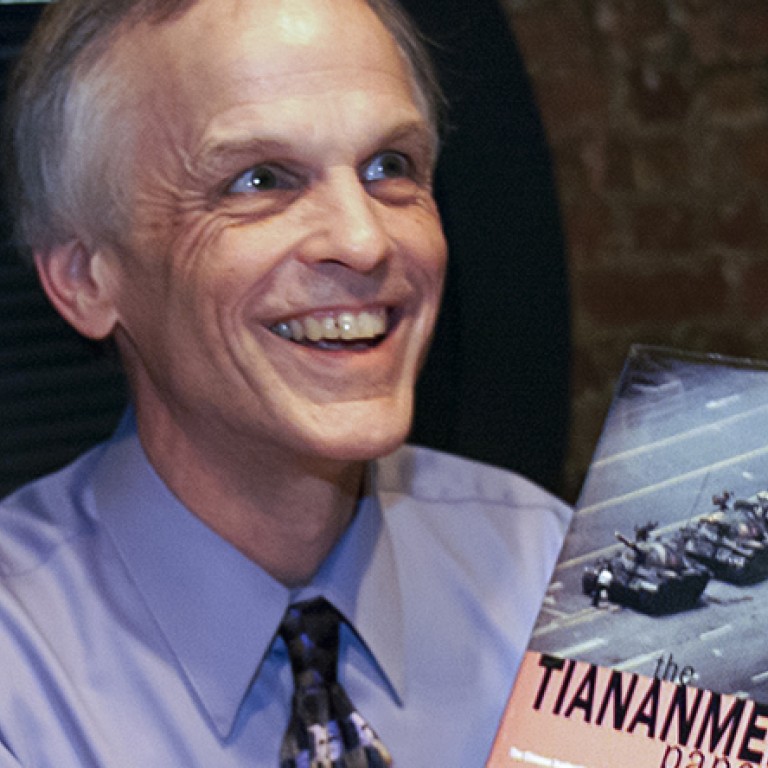

Perry Link, professor emeritus of East Asian studies at US university Princeton, co-editor of and the writer who coined the phrase "the anaconda in the chandelier" to describe the mainland's censorship machine believes Vogel's edited version has ended up pandering to Beijing.

"The 10 per cent that is omitted from Ezra's book is not a random 10 per cent," he tells . "It is a 10 per cent that distorts the reader's overall impression of the whole - i.e., the other 90 per cent as well. Ezra's book is very favourable to the regime. If 10 per cent is omitted, it reads like a flat-out, all-out endorsement by a Harvard professor of Chinese Communist Party authoritarian rule."

Peter Hessler, Osnos' predecessor at , argues that writers bear a moral responsibility to be accountable to the people they are writing about, which must be weighed against the cost of censorship.

"An absolutist stand can be a way of disengaging or not thinking hard about a situation," he says. "It's an unhealthy dynamic that is common all over the developing world - the foreign correspondent often feels like he's exporting stories. He doesn't receive local feedback and there's a risk that he isn't fully accountable to his subjects."

Hessler has published two books in the mainland - and . The cuts inflicted "did not strike at the core" of either book, he says: came out minus 4½ of its more than 400 original pages and fared slightly better, having two pages shaved off out of more than 440. Since Hessler tends to focus on local communities rather than political leaders (such as Vogel's ) or dissidents (like Osnos' ) his work is much less sensitive. Publishing was "a compromise, and one that doesn't make me completely happy, but I believe it's worth it", says Hessler.

He didn't bother looking for a Chinese publisher for his third book, however. In part, follows the fate of Polat, a Uygur man strongly critical of the government. Hessler knew the censors would have had a field day. "It would be an insult to Polat if I gave the Party control over his story."

Like Hessler, American author Michael Meyer focuses on local lives as a way to explain the wider changes happening in China. He also agreed to minor cuts because of a moral duty to the people he wrote about. His , which details his daily life in a dilapidated courtyard house south of Tiananmen Square, was released in the mainland last year, with one of its 400 pages missing.

"Western journalists rarely raise this point: we are writing about Chinese people in English, and the work is read by Westerners. I spent three years living in a shared courtyard heat and plumbing, sharing the house with several Chinese families, and volunteering in the local elementary school. I care a great deal about them and the neighbourhood, and so, of course, I wanted them - and the people making decisions about the neighbourhood's fate - to read the research and their stories."

However, Meyer won't be looking for a mainland publisher for his new book, , due out at the end of this year.

"There is so much banned history - in particular around the events of the second world war and the Chinese civil war - that I think too much will be deemed too sensitive to publish on the mainland. I will not agree to those cuts, or anything about the lives of the villagers with whom I lived."

When the censorship is deemed too damaging, there is a middle way.

James McGregor is a Beijing-based American journalist who focuses on business in China. A year after his bestseller came out in 2005, publishers sounded McGregor out about doing a local version.

"They were proposing cutting so much out that the book would have been a thick brochure," explains McGregor. "Instead, a young man approached me and asked if he could translate it and put it on the internet. I let him do so and now many, many people I meet in government, business and the media have read the internet version. That's fine with me."

The online version is free and faithful to his original, says McGregor.

point out how brave they are for either publishing in China or not, but no one talks about the Chinese publishers who are taking these risks, trying to show Chinese readers a wider view of their country," says Meyer.

"There's nothing heroic about a foreigner publishing in China, just as there's nothing heroic about a foreigner not publishing in China," says Hessler. "But some of the Chinese who work in this field take risks and they can be punished for what they do."

Vogel expresses gratitude to his publisher, Sanlian, whom, he writes, "was creative in thinking about ways that would permit controversial parts to remain".

Local editors are caught in a system not of their making. Outspoken Chinese journalist Chang Ping, who now lives in Germany, says, "The market in China for foreign books is indeed an extremely large market. While money is the first consideration for the [publishing companies], I believe that the majority of editors are disgusted with censorship and try their hardest not to censor."

A Shanghai-based publisher, who asks to remain anonymous, explains that books are either looked at by an in-house censor or, if it is a very sensitive title, the work is sent to a government department. The latter course of action usually results in extensive cuts.

"In my experience, it makes the censorship less damaging if the censors are your chief editor or proprietor," the publisher says. "Although they are always communists, they are more flexible and market-oriented. Sometimes you can make an argument face to face and change their mind. The worst thing is being censored by the government. You don't even know who the censor is. Everything is out of your control and you are able to do nothing except wait for a final judgment."

The rules of censorship are never explicitly stated and change according to the political climate. There are certain constants - Tibet, Taiwan, top leaders and Tiananmen Square are always among the most sensitive topics - but other issues fall in and out of favour.

Meyer says that five years ago there was no way he could have published a mainland version of .

"Statistics on the razing of historic neighbourhoods, on the amount developers illegally pocketed … the discussion over what constitutes heritage" were all issues that were too sensitive, he says. Yet last year his book was published virtually unscathed.

"I have no idea about the ban at all," he says. "I guess, perhaps, I have been a problematic figure to the government and have been on some kind of list. The publisher couldn't say for sure."

Ha Jin's tales are often set amid sensitive events such as the Cultural Revolution, the Korean war or the Tiananmen Square crackdown.

"Because of the severe censorship in China, I do not care about publishing the simplified Chinese version of my books any more," says Ha Jin.

Osnos has decided not to publish on the mainland as the reach of the country's censorship machine is extending. Foreign filmmakers, news organisations, internet companies and scholars have all made concessions to censorship in recent years to gain access to mainland markets. Most recently Bloomberg was accused of quashing a story about the wealth of top leaders because it was worried Beijing would punish the American news agency if it published the piece.

"I'd say academia and filmmaking are two areas where China really is exporting censorship," says Abrahamsen. "In both cases, it's a matter of access: people are willing to accede to government demands in exchange for continued access to information or markets. As Chinese society comes into greater contact with other societies and governments, I expect that these sorts of collisions will become more and more common."

If foreign writers increasingly make concessions to publish in the mainland, the danger is that censorship will become the accepted norm.

"As more news organisations, internet companies and others look for a larger presence in China, they will make decisions about the terms of their involvement," says Osnos. "There are many ways to be in China, and not all of them are created equal."