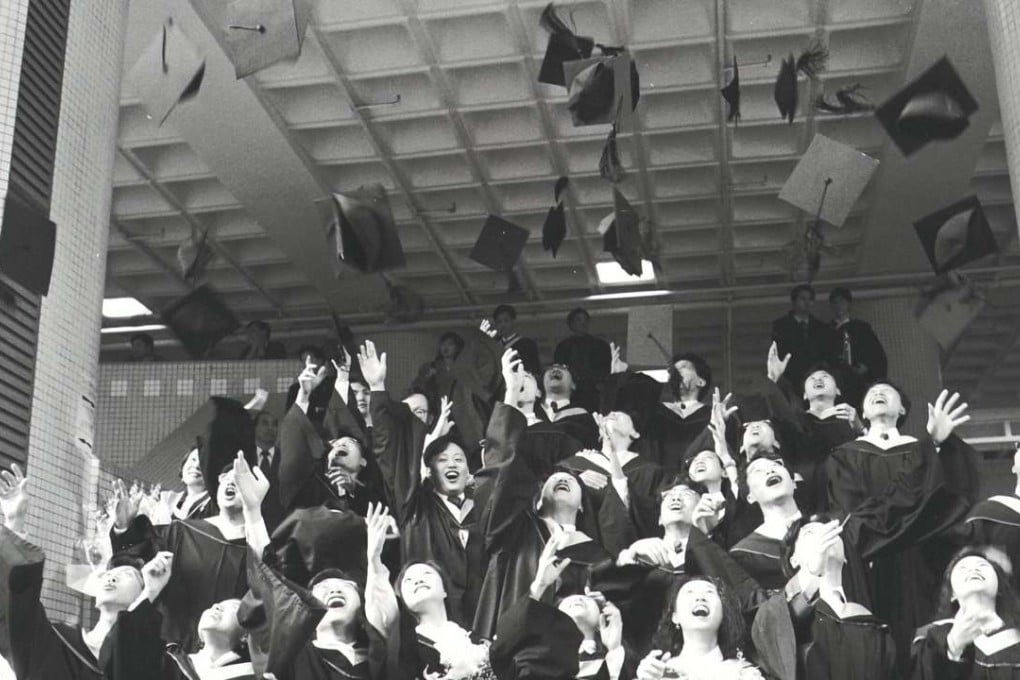

Then & Now | College degree – worthwhile or just a piece of paper?

Unlike in the past, higher qualifications don’t necessarily translate into higher paying jobs these days

Mass inflation’s headlong “race to the bottom” occurs when – seemingly without warning – the general public realises that the over-issued, poorly backed currency they possess is, ultimately, just coloured paper.

Recent news reports that local associate degree holders earn – after two years of self-funded study – about the same as secondary-school leavers have caused academic soul-searching. A senior official from one leading institutional provider of these courses opined – with unintended irony – that Hong Kong’s employment market has readjusted itself to the large number of sub-degree graduates.

Let’s face it, everyone involved in Hong Kong’s higher education sector is complicit; students know when course materials, lecturers and examinations are unchallenging; academics wilfully look the other way at collapsing standards; administrators remain obsessed with expanding their particular college’s league table rankings; and institutional bean-counters nickel-and-dime everything in sight. As ever, nothing makes people less likely to “know” something than when their jobs and promotions depend on not knowing it. And so it is with this particular local Ponzi scheme.

Historically, social mobility in Chinese society devolved from education; the literate seldom starved, which was why poor families readily sacrificed themselves to provide educational opportunities. In modern times, qualifications could be readily monetised. Primary level was required for all but the most menial jobs by the 1970s while secondary graduates were paid more depending on whether they had achieved Form One, Form Three or Form Six standard. Specific technical qualifications added extra pay; post-graduates earned more than undergraduate-degree holders, and so it went on.

Individuals, therefore, can track quite closely what they feel they should earn from their alleged educational attainments. When this particular currency becomes widely devalued, youth unrest is an inevitable consequence. And when the job interview question “Did you go to university?” becomes “Which university did you go to?”, grade inflation problems are starkly apparent. Britain, Australia and the United States have similar problems.

But what about the other end of Hong Kong’s academic spectrum – the taught master’s degrees that are among the tertiary education industry’s biggest money-spinners? A breathtaking array of speciality courses – which all lead to a degree, of sorts – appear every autumn, and new products constantly enter the market. While the Hong Kong mania for collecting pieces of paper offers a key motivation, widespread anecdotal evidence indicates that women – and, to a lesser extent, men – of a certain age become serial master’s-degree candidates in the hope that their “classmate circle” might eventually provide a hard-to-find partner.