When packaging in Hong Kong meant sago or rattan, before plastic bag nightmare began

Long before the era of plastic packaging that, when carelessly discarded, fouls our seas, reusable sago and rattan, or old newspapers, were used to wrap fragile goods and food items

Home-grown consumerist nonsense aside, reliable packing material has been an essential component of any well-developed market economy for millennia; without dependable packaging, spoilage of fresh products, and damage of fragile items, would make many traded goods uneconomical. For centuries, packing materials were imported into China to enable high-value items to be exported with minimal breakages.

Probably the most surprising packing material used in earlier times, when seen from today’s perspective, was sago. This tropical starch remains best known – especially among those unfortunates who don’t know how to cook it properly – as a glutinous, milky-grey, horror-story pudding served up in the refectories of second-rate British boarding schools. But from the early 18th century onwards, sago (and its counterpart, pearl tapioca) was imported into China from Southeast Asia in massive quantities as packing for porcelain.

Crockery that was wrapped in straw paper, surrounded by sago, and packed tight in wooden kegs, could survive rough transit by sea and land to markets in Europe and North America. Sago was, in essence, the polystyrene packaging of its day. But unlike polystyrene, sago didn’t end up poisoning landfills and seas; as an edible starch, it was sold off cheaply at the final destination, evolving into an inexpensive, European-style milk-pudding base or soup thickener.

Rattan was another Southeast Asian material imported to facilitate exports. Tea chests were lashed together in the holds of ships using this flexible, non-aromatic vine. Rattan ensured there was no contamination of tea cargoes by resins from pine, camphor or other timbers. It was also light, which reduced the ship’s payload.

And like sago, rattan had a practical alternative use; it could be used for furniture manufacture. Cultivation of various species of calamus, a genus of rattan palm, was introduced into south China in the 19th century, and these trailing, prickly plants can still be seen in various corners of Hong Kong – the Colonial Cemetery, in Happy Valley, contains rattan clumps on remote hillsides.

Most other market purchases, such as vegetables, were tied up with sea-grass twine – a profitable cottage industry in isolated, otherwise impoverished coastal villages. Even after they’d carried the shopping home, newspapers had a final domestic destiny; either they were crumpled up and used to start the kitchen fire or deployed for a last, basic flourish before being flushed down the lavatory.

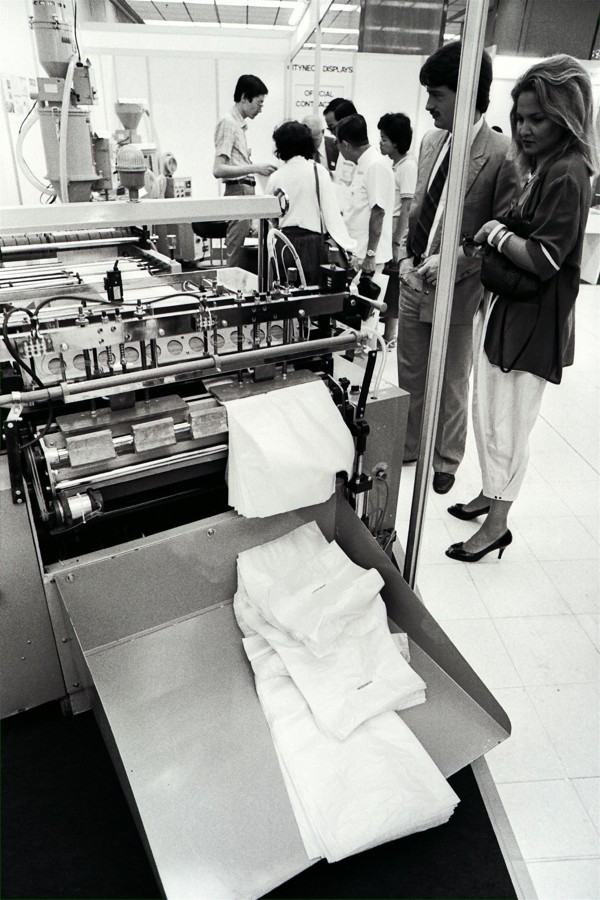

Hong Kong’s plastic-bag nightmare started in the ’60s, as a by-product of the local plastics industry. Remnants from other plastic manufacturing – anything from misshapen doll’s heads to trimmings from extruded plastic kitchenware – were gathered up, melted down and rolled out as carrier bags. As plastic bags took over from old newspapers (and kerosene, gas or electric cooking fires and cheap manufactured toilet paper superseded their other functions), the land and marine pollution these non-biodegradable items generate also steadily proliferated.