Remember the shrewd gold-toothed amahs? Dentistry in Hong Kong has come a long way since then

Japanese dentists were popular in pre-war Hong Kong for their workmanship, and refugee dentists from China thrived in the Kowloon Walled City in the post-war years, until a shortage of professionally qualified local ones eased

Throughout human history, one unavoidable fact of ageing has been the gradual loss of one’s teeth. While dietary, heredity and environmental factors all either hastened or delayed the inevitable, having a mouth with more gaps in it than teeth was eventually “just one of those things”.

By the mid-19th century, dentistry practices had evolved, bringing the manufacture of orally inserted plates of false teeth. Early dental plates held human teeth (mostly sourced from unclaimed corpses) but, as time went on, porcelain versions became available.

As good dentistry became widespread, the habit of filling carious teeth with gold grew popular. Period memoirs from across the Far East, including Hong Kong, have as a stock figure the gold-toothed domestic amah who shrewdly kept a portion of her savings tucked away in gold fillings.

Aesthetics aside, the reasons for this were eminently practical. If a person needed to flee from flood, famine, warlords, foreign invaders or some other calamity, then what could be more secure than an immediately realisable asset anchored in one’s mouth?

From the early 20th century onwards, Hong Kong’s more popular dentists were expatriate Japanese.

One reason for the influx of Japanese dentists, who established thriving practices in cities across the Far East, was the large number of Japanese sex workers then resident in port cities. An otherwise pretty prostitute with nasty rotting teeth, and correspondingly foul breath, would naturally lose customers and income.

Getting them fixed, therefore, was an investment that both the woman and her employers considered worthwhile. Prices were reasonable, and Japanese workmanship was good – especially for the dental plates then coming into vogue, which employed high-quality, naturally tinted Japanese porcelain for artificial teeth.

And more than a few were eventually proven to be so; post-war memoirs recount stories of long-established Japanese residents who had quietly vanished by late 1941, as war became imminent, and reappeared a few months later, after successive Allied surrenders across Asia, in military uniform and with a more fluent command of English, Dutch, French and other languages than they had hitherto shown.

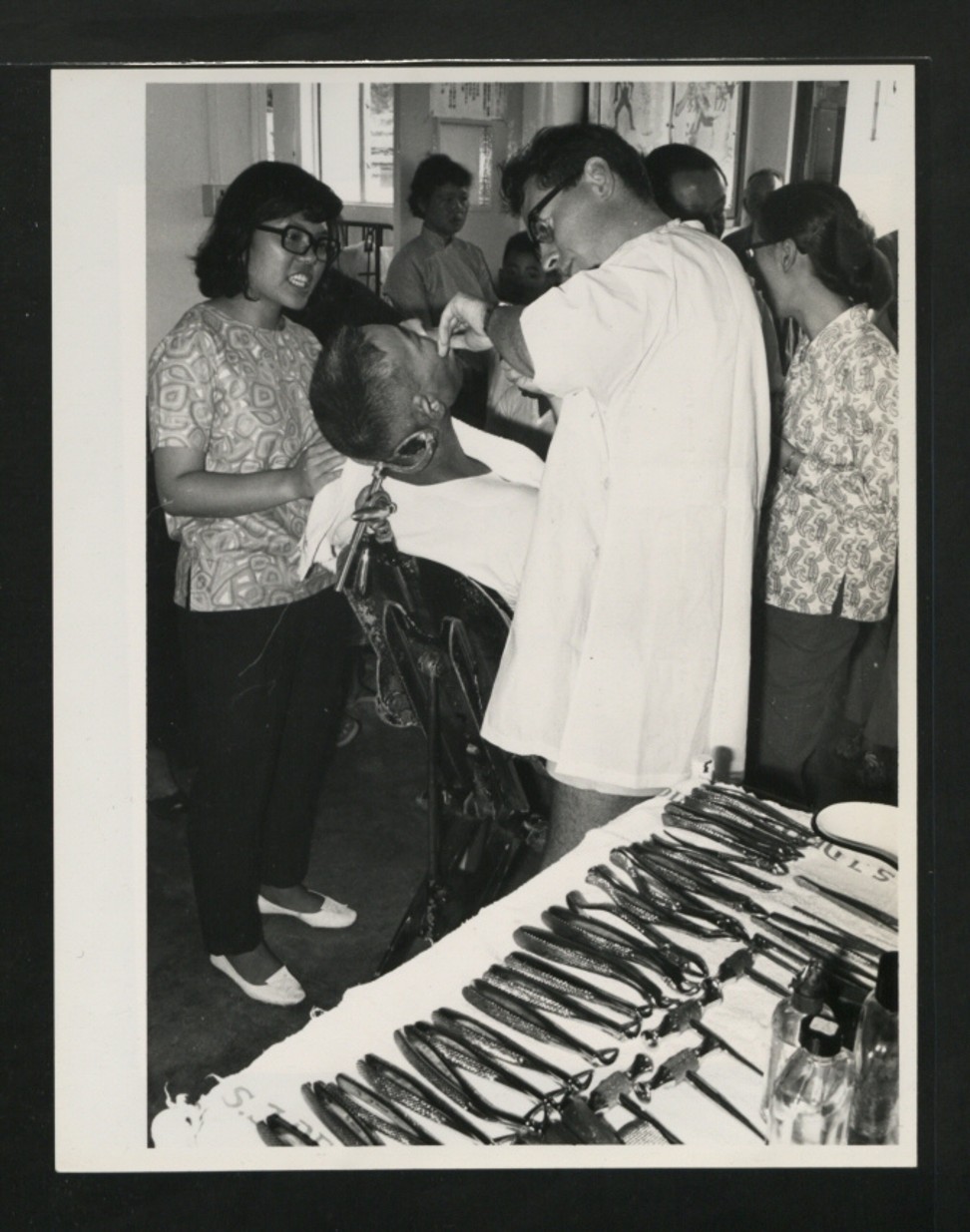

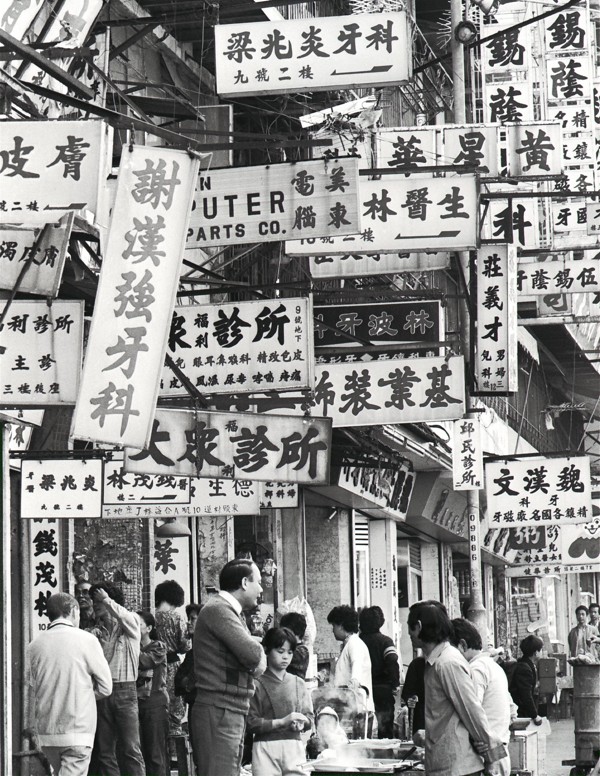

In the post-war years, numerous refugee doctors and dentists from China, who were unable to get professional accreditation locally, due mostly to “closed shop” trade union practices, established businesses in the jurisdictional grey area of Kowloon Walled City.

Standards and fees were reasonable, and open-fronted dentist’s shops remained a local feature until the area was cleared and finally demolished in the early 1990s.

Advertising was vitally important; “before and after” photographs of ghastly crooked fangs transformed into gleaming pearly smiles of the sort usually seen in American toothpaste advertisements were a staple of these now vanished backstreet establishments.

Prince Philip Dental Hospital, in Sai Ying Pun, was opened in 1981 in partial response to a deficit of properly trained dentists. This facility comes under the Faculty of Dentistry at the University of Hong Kong, and two-thirds of all dentists who now practise in the territory received all or part of their professional training there.