Language Matters | Where English took the words ‘tycoon’ and ‘honcho’ from – you may be surprised

Though one sounds Chinese, and the other Basque, these two terms for powerful people both entered the lexicon from Japan; one was subsequently used as a nickname for Abraham Lincoln

Many Japanese words used in English began as cultural borrowings to introduce new concepts. There are words from traditional Japanese culture, such as geisha, tatami, karate and onsen; words used in the appreciation of nature (sakura, bonsai); and to describe delectable cuisine (sashimi, sushi, sukiyaki, sake). Even the fifth taste – unami – is Japanese.

In contemporary culture there are manga, karaoke and kawaii. Anime is clipped from animashon (Japanese for “animation”, and borrowed back into English to describe Japanese cartoons). Karaoke comprises kara (“empty”) and oke, clipped from okesutora, the Japanese for “orchestra”. But some words are not so obviously from Japan. Hong Kong is home to many “tycoons” – isn’t that derived from Chinese? And head “honcho” must be Basque, right?

Let’s lay those two myths to rest: both words come from Japan, a result of contact between America and the Land of the Rising Sun, initially with diplomatic and military contexts.

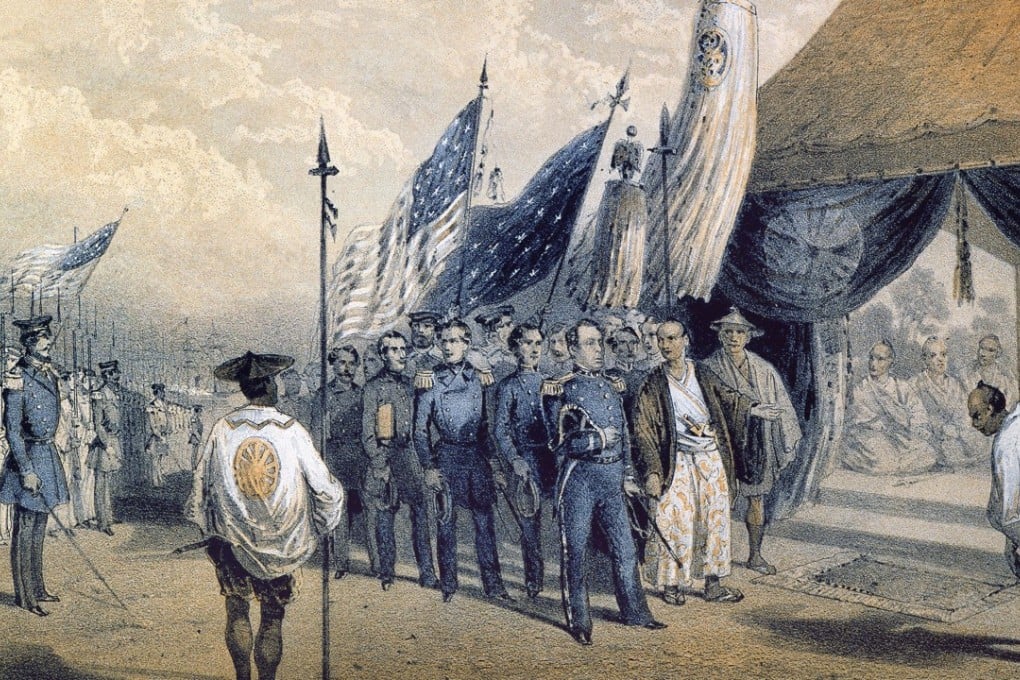

The story of “tycoon” begins in feudal Japan, which had been closed to external trade for two centuries when American naval officer Commodore Matthew Perry, aiming to open commercial relations, arrived in 1853.

Perry carried a letter from the United States president, insisting on negotiating with the highest-ranked Japanese dignitary. The ruling Tokugawa shogun (hereditary commander-in-chief, with de facto absolute power) required a title for diplomatic communications that conveyed more grandeur than “supreme military commander”, yet not using “emperor” or “king”. Thus came into being taikun, or “great lord” or “prince” (from the Chinese ta kiun).