Hong Kong’s refusal to order 2016 riot inquiry, and what it means for the city

Public inquiries into major incidents – to establish what went wrong and lessons learned – have been routine; the failure to order one after Mong Kok violence shows officials don’t want to hear answers to honest questions

At various times in Hong Kong’s past, when typhoons, floods or landslides occurred, an official commission of inquiry was immediately ordered. The same response followed ferry disasters, tunnel collapses and other calamities, especially when they involved significant injury or loss of life, and where quantifiable human error might have been responsible.

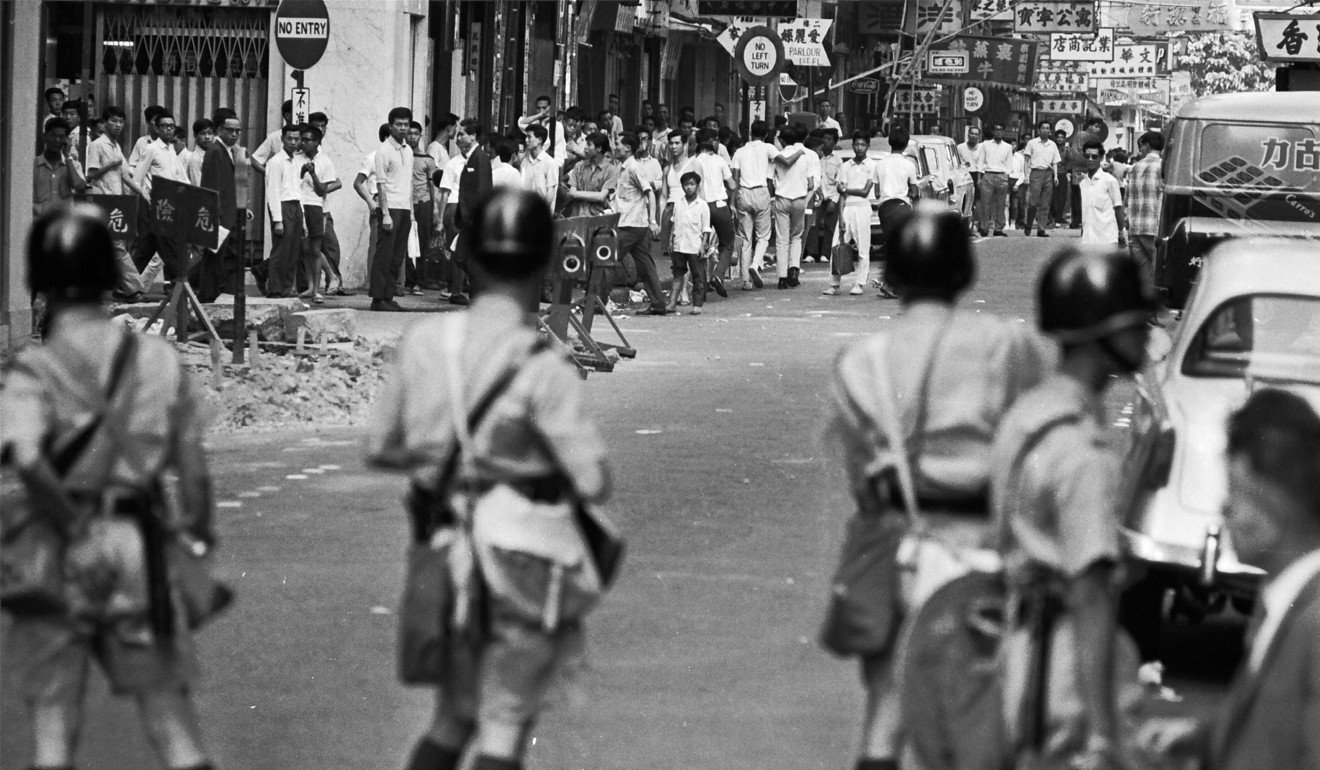

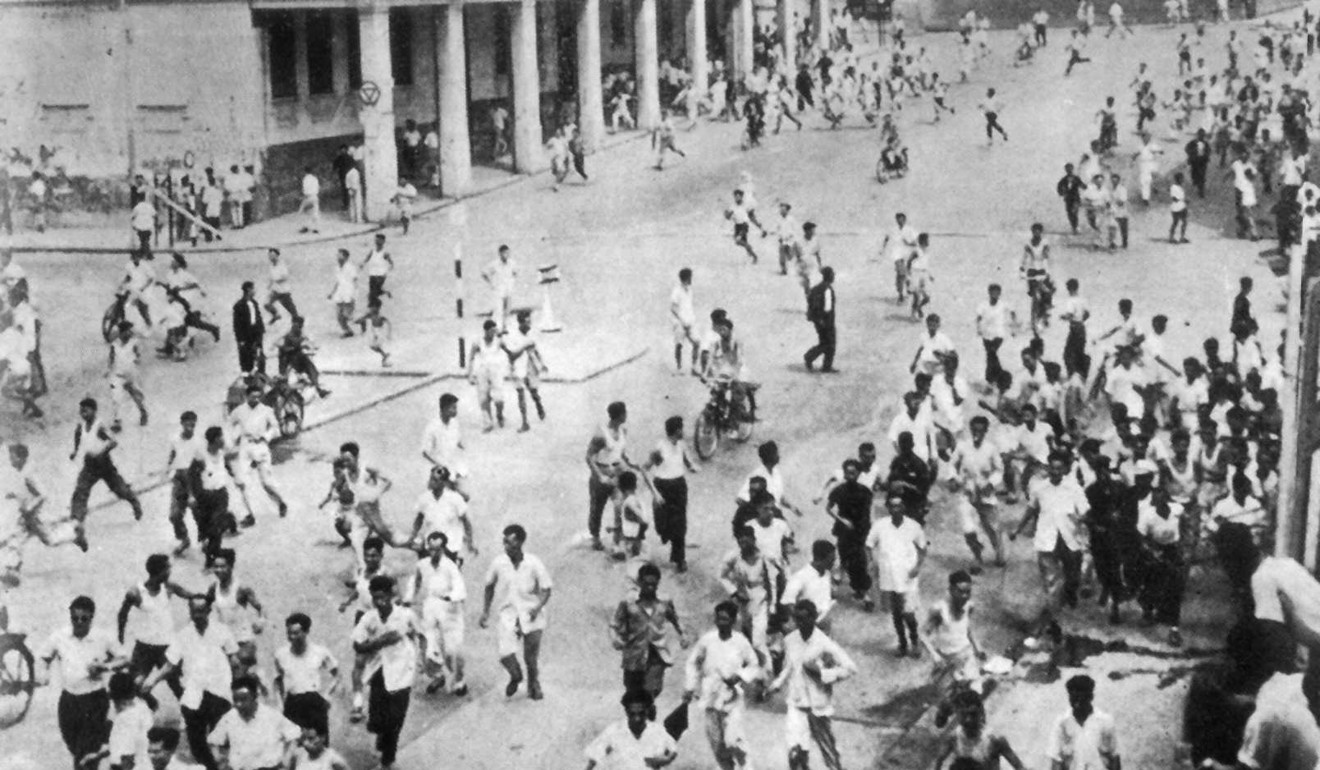

A similar approach was followed when long-simmering socio-economic or political unrest boiled over into street violence. A commission of inquiry, with members selected to be – at least superficially – impartial and objective, was swiftly convened, with orders to get to the bottom of what had happened.

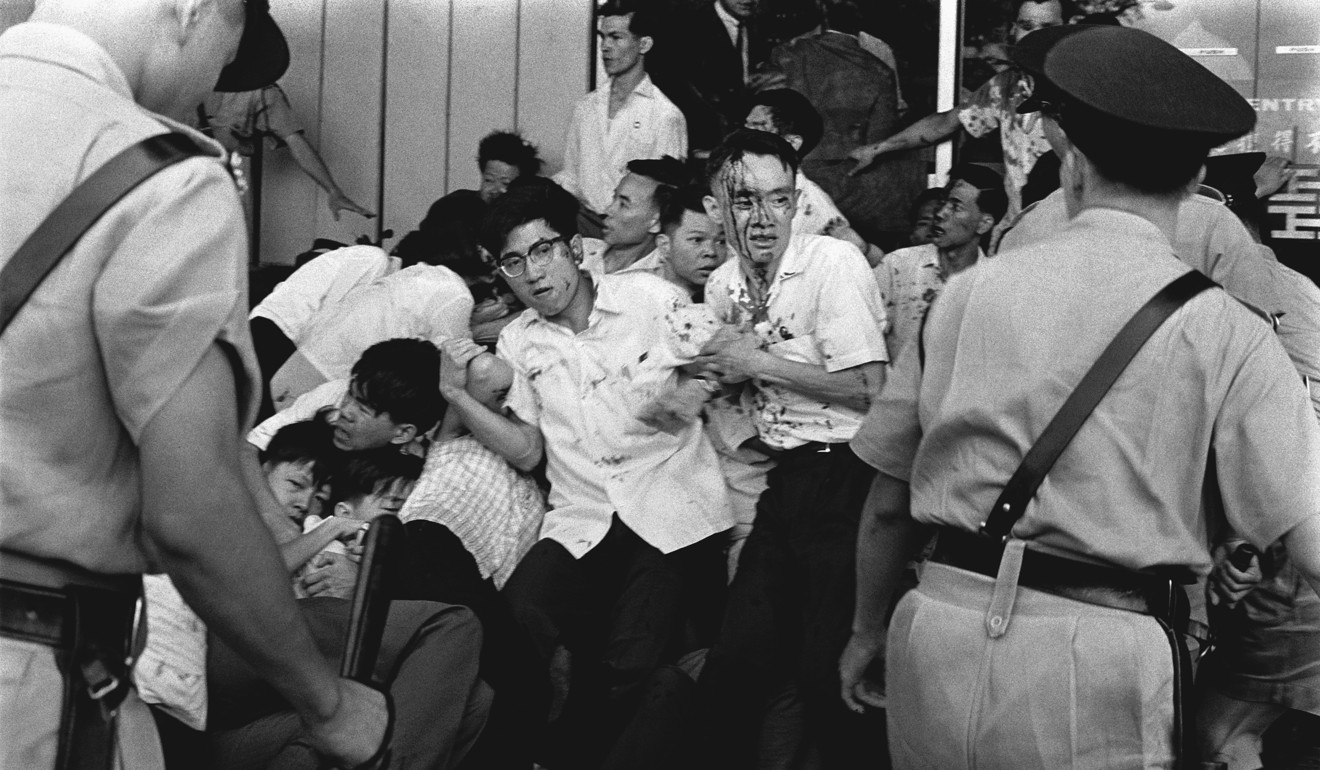

This sequence of events repeated with each of the three significant outbreaks of politically fomented violence that occurred in Hong Kong after the second world war; the Nationalist-caused 1956 Kowloon disturbances, the 1966 Star Ferry fracas and, most significantly, the 1967 Communist-orchestrated mayhem that left more than 50 people dead and hundreds injured, through street violence, bombings and arson.

Outwardly, the main functions of these inquiries were to dispassionately document and evaluate the immediate and more general causes of the unrest, and the strengths and shortcomings of the official response to them. The aim was to determine what could be done better, or differently, should similar circumstances arise in the future.

Eventual opening up to public scrutiny of official files in Hong Kong, Britain and elsewhere, and additional revelations in interviews, memoirs and other first-hand accounts, afford a different historical perspective to what, over time, has become generally “understood” to have happened.

‘An inquiry into the Mong Kok riot would only create a new battleground’

Newly released archival material makes it obvious that an unstated objective for past commissions of inquiry was to deflect blame from certain groups or individuals, and pin the principal burden of responsibility in the public eye – fairly or not – on others. Festering socio-economic or political issues were swept under the rug in the hope that these factors would, somehow, magically resolve themselves over time, without further official examination or intervention.

If they had occurred during the first decade or so after the handover, in 1997, when Hong Kong retained at least the facade of a local government with reasonable autonomy over internal affairs, a commission of inquiry into the public disturbances in Mong Kok on February 8, 2016, following a crackdown on illegal street food hawkers, would almost certainly have been convened.

Lunar New Year clashes in Mong Kok did not amount to riot, court told

Whether anything substantial would have been achieved by this is another matter; but at the very least, a more-or-less creditable game of public accountability charades would have been orchestrated.

In the immediate aftermath of the events in Mong Kok, then chief executive Leung Chun-ying – in lockstep with other senior officials – labelled the fracas a “riot”, and the term has since been universally used in government pronouncements about the civil unrest.

Deploying such a serious label for what occurred would appear to justify an equally conscientious examination of the causes. Instead it serves only as a wholesale, unevaluated, un-nuanced condemnation of the unfortunate events that unfolded on that February night.

The current government’s disappointing, yet thoroughly predictable, blanket refusal to establish a formally constituted inquiry into the “fishball fracas”, more than two years after it happened, sets an unwelcome precedent for official responses to similar future occurrences. The underlying message is clear; if you don’t want to hear – and then have to deal with – the likely answers that asking honest questions in public will elicit, then it is safer not to ask them.