China’s newest film festival a hit in provincial Pingyao, with cinemas packed, young directors championed, John Woo mobbed

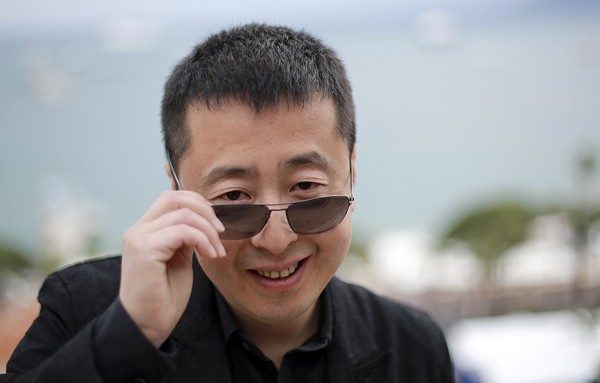

Filmmaker Jia Zhangke’s dream of launching festival in his home province of Shanxi comes true, with warm reception for cutting-edge Chinese directors, recent Cannes debutants and old hands like John Woo in Unesco heritage city

A t the world premiere of Depi last month , 15 minutes before the film was due to start, the cinema was almost full. By the time the movie began, young people were clogging the aisles, leaning against walls and sprawled on the floor, much like the youthful Godards and Truffauts who crammed into the Cinémathèque Française every evening in the 1950s, watching anything and everything that unspooled before them.

But the Depi screening was not held at so hallowed an institution as the Cinémathèque, nor in a cosmopolitan metropolis such as Paris. It took place in a former diesel-engine factory in the city of Pingyao, in Shanxi province in northern China, a place best known among travellers for its walled old town.

The premiere of Hu Yichuan’s film – a relationship drama set in a Shanxi village – took place during the Pingyao Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon International Film Festival, the first gathering of its kind to be held in the Unesco heritage-listed ancient city.

Depi served as curtain-raiser on a programme section dedicated to young talent and local stories. And young locals really were everywhere inside the Pingyao Cinema Palace, a vast, modern complex of cinemas, exhibition space and cafes. The crush for Depi was a mild affair compared with the long lines (and last-minute scrum) at the auditorium hosting a masterclass by Hong Kong’s John Woo Yu-sum (A Better Tomorrow [1986]; Hard Boiled [1992]), and the cafes burst with youthful customers nursing coffees between screenings.

“At every screening I went to, at least half the audience was local; maybe not all of them from Pingyao, but from cities in Shanxi,” says Marco Müller, the festival’s Mandarin-speaking artistic director. The Italian first came to China as a postgraduate student, in the mid-1970s, and helped introduce Chinese cinema to Europe during spells heading up festivals in Locarno, Rotterdam and Venice, before heading back East to work on similar events in Beijing, Fuzhou, Macau and now Pingyao.

Müller says he doesn’t possess a “mandate” to educate people, but believes the festival should be responsible for “raising cultural awareness” of films beyond the commercial mainstream and contribute to the growth of China’s young, so-called “art house” demographic.

Citing such luminaries as Jia Zhangke, the award-winning filmmaker who originally proposed the festival, Müller says China will have an art house audience of 40 to 50 million people in three years’ time. Pingyao was chosen as the festival venue to help redress the lack of arts and culture experiences outside major conurbations and provincial cities.

Having grown up in the Shanxi city of Fenyang, this was especially important to 47-year-old Jia.

The director shot his breakthrough film, Platform (2000), in Pingyao, and had long planned to host a festival locally to help residents understand and appreciate the endeavours of young filmmakers. Having established a company for that purpose, Jia invited Müller to join him as the festival’s artistic director two years ago.

With his own contacts and expertise, and that of the eight programmers on his team, Müller secured a number of high-profile and acclaimed films that recently premiered elsewhere on the festival circuit. These included Cannes hits such as Andrey Zvyagintsev’s Loveless, Valeska Grisebach’s Western and Pedro Pinho’s The Nothing Factory, as well as autumn-festival debutants: Elizaveta Stishova’s Suleiman Mountain, Aida Begic’s Never Leave Me and Ruth Mader’s Life Guidance.

Showcasing work by young Chinese filmmakers is central to the Pingyao gathering, says Müller, and these included both films by overseas-educated filmmakers such as Chloé Zhao (The Rider) and Qiu Yang (award-winning short A Gentle Night), and domestically made films that have secured exposure and praise internationally (Zhou Quan’s End of Summer; Pengfei’s The Taste of Rice Flower).

Rookie Chinese filmmakers enjoy the opportunity to present their work to the army of foreign journalists, critics and programmers that the festival brings to town. As well as Depi, home-grown titles this year included Sun Liang’s Kill the Shadow, Han Dong’s One Night on the Wharf (produced by Jia) and Li Jiaxi’s However, a rite-of-passage drama that received only limited release in Shanxi in July.

Müller aims to make the festival sustainable by building bridges not just between filmmakers and investors, but also between distributors and audiences. Expanding the Beijing and Shanghai festivals would only lead to the featured films competing against each other for attention, he says; “boutique” events like Pingyao allow more space for each title to flex its artistic muscles.

Staying on the right side of authorities will be important to the festival’s future, but Müller is confident in that respect, saying that Shanxi’s officials were “incredibly helpful” in the run-up to the event, and that the province’s censors – who were charged with examining foreign films for the first time – required only “slight edits” to three films: for nudity in Arnaud Desplechin’s Ismael’s Ghosts, to sex scenes in Loveless, and to jokes about China in Anurag Kashyap’s The Brawler.

“We have to imbibe ourselves with self-censorship,” Müller says, recalling how he and his team selected films for the festival. “It’s the only way. The festival was happening right after the 19th congress [of the Communist Party] – we would not have had a chance. It’s quite obtuse to test censors’ limits anyway.”