Chinese filmmaker stuns Cannes Film Festival with documentary revealing horrors of Mao’s gulags

Eight-hour film Dead Souls the result of painstaking search for the few survivors of ‘re-education’ hard labour camp in 1950s

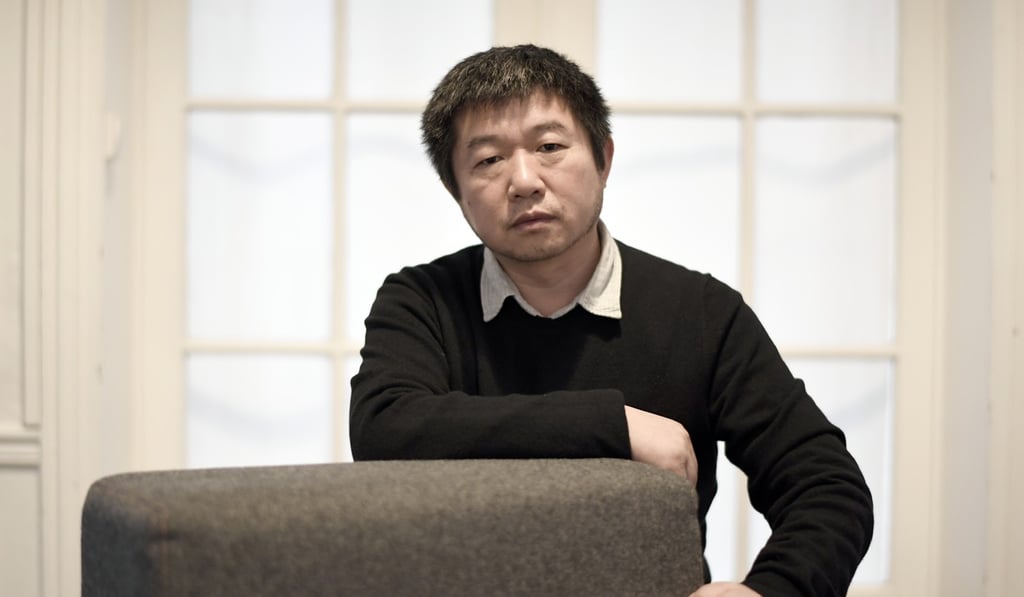

Clocking in at more than eight hours, Wang Bing’s latest outing, Dead Souls, is probably one of the longest films to have taken a bow at the Cannes Film Festival, where it premiered on Wednesday, in two parts, with an hour-long intermission in between. The work’s length is, in a way, a reflection of Wang’s own odyssey in completing the documentary.

Based on interviews and footage he gathered over 13 years, Dead Souls reconstructs the pain and suffering of those condemned to “re-education” – a euphemism for hard labour – in a gulag in northwestern China at the start of Mao Zedong’s Anti-Rightist Campaign, in 1957.

“The filming of Dead Souls began around the same time as the preparations for my fictional feature The Ditch,” says Wang, referring to the 2010 film about Jiabiangou, a labour camp in Gansu province. “I got to know a few people who made it out of the camp alive, and filmed in-depth conversations with them. After that, I thought I should search for all the survivors and conduct thorough interviews with them.