A filmmaker remakes a classic documentary about a homeless woman – without the male bias

- Constanze Ruhm’s version of ‘Anna’ gives a voice to the protagonist of the original film

- In doing so, she highlights the way that women have long been exploited by the film industry

When Austrian filmmaker Constanze Ruhm signed up to Living Archive, a project in which artists are encouraged to appropriate and rework the films and footage stored in the vaults of the Berlin cinematheque Arsenal, one title caught her eye. Having spent her career exploring representations of women in cinema, she was drawn to Anna, a 1975 documentary about a fragile teenager in Rome, Italy.

While Ruhm considers Alberto Grifi and Massimo Sarchielli’s documentary a masterful work of art, she also acknowledges the problematic nature of its genesis.At the time, Grifi was famed for barrier-breaking shorts about Hollywood ( Verification Uncertain, 1964) and maverick psychiatrist Wilhelm Reich (Long Live the Orgonauts!, 1970), and critics lauded Anna as an explosive piece of cinema verité.

While Anna has long been deemed a classic, it is flawed. Ruhm considers the film a mix of “empathy, detached observation and exploitation”. Even Grifi said as much about his film in the 1990s, when he described his protagonist as a “guinea pig” in an exercise driven by “poorly concealed sadism”.

All this begs the question of what to do with these tainted “classics”: the #MeToo era has brought this into sharper focus as critics debate how one should view Last Tango in Paris (1972), or all the films Roman Polanski made alluding to his self-proclaimed victimhood amid “mass hysteria”. Some call for a boycott, others try to separate the aesthetics from the approach. Ruhm opted for a third way: confronted by the controversial complexities of Anna, she produced a new film that sought to update and “repair” the story.

Making its debut last month in the Berlin Film Festival’s Forum section, The Notes of Anna Azzori / A Mirror that Travels through Time not only gives voice to the young woman in the original documentary – the title reveals her full name for the first time – but also to others who have been oppressed and marginalised in a predominantly male-driven film industry and society.

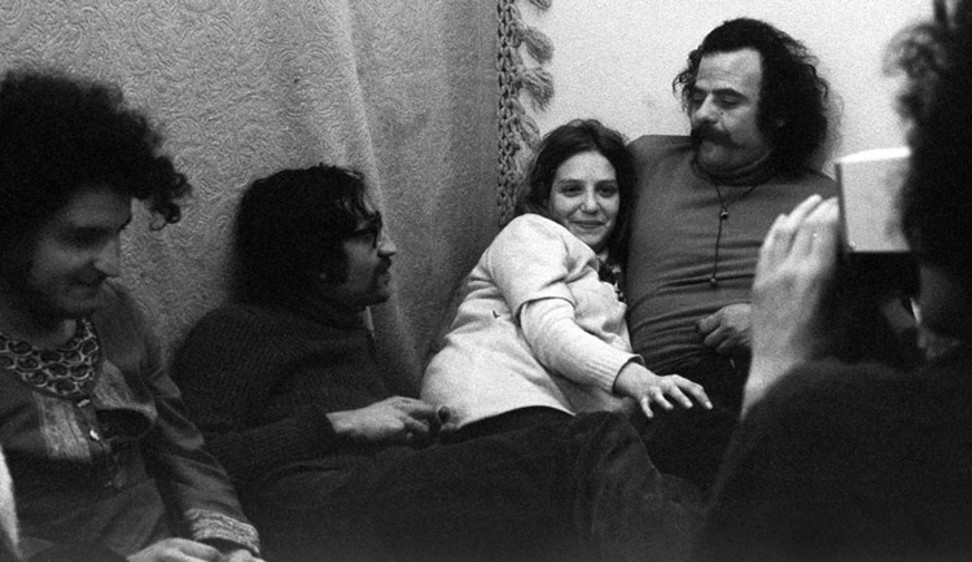

The original Anna began in February 1972, when Sarchielli met a homeless, heavily pregnant and drugged-up 16-year-old in Rome’s Piazza Navona. The actor-director took the teenager home and offered her food and shelter; in exchange, he and Grifi filmed her up close for a year with the intention of producing a film about her and the social circumstances that shaped her existence.

At the instigation of the directors, she strips herself bare for them and their camera both literally and psychologically. Flaunting wrists with barely healed scars from suicide attempts, she recalls the abuse she received in various rehabilitation institutions. She engages with the filmmakers in ways that sometimes seem disturbingly intimate. In one scene, she shoots milk from her breast onto Sarchielli’s gleeful face.

Watching the film now, it is hard not to cringe at the way Grifi and Sarchielli grapple with their subject. From the start, they freely admit to wanting to “save” Anna from herself; that it would be up to them to make her “aware of her existence”. In the same conversation, Grifi says they would make a film based on Anna’s notes. Then he chuckles and corrects himself: “Sorry, notes taken by Massimo about Anna …”

Four decades later, Ruhm is not letting Grifi get away with that. Replaying this scene in her film, when Grifi implies Anna couldn’t write anything as intellectually consuming as “notes”, a voice-over asks, “Why are they laughing?” It’s the first of many instances in which Ruhm questions the way male filmmakers have marginalised women. The Notes of Anna Azzorialso adds to the original footage. Ruhm constructed a free-flowing essay around an army of actors auditioning for her updated version of Anna. While they pose for screen tests, a voice-over gives details of each actor’s background, views about the world and what cinema means, and perhaps most importantly, reaction to the original documentary.

This is a rebuttal of Grifi’s own comments in his film about his saviour-like role in granting Anna some meaning in her life. Ruhm is stating strongly and clearly that her actors come with their own personalities and views: they don’t need powerful directors – especially male ones – to provide enlightenment for them.

Ruhm’s film includes images of feminist demonstrations in Rome and specifically in Piazza Navona, where the directors “found” Anna. Spliced into this footage is a scene from Antonio Pietrangeli’s comedy I Knew Her Well (1965), in which a young, provincial woman (Stefania Sandrelli) is ushered into a shoot for photographers to take pictures of her feet in fetishised boots.

The scene illustrates perfectly the objectification of women in the razzle-dazzle of high-society Rome. But perhaps Ruhm also has in mind one of that film’s most important twists, when the young woman discovers her writer-lover is using her as source material for his latest novel.

Ruhm’s message is that such exploitation has to stop. “We’re the protagonists of our story,” says one on-screen text. In another scene, Ruhm’s “Anna” steps behind the camera and composes a shot through the viewfinder, subtitled: “Changing the frame.”