Netflix series Beef: Ali Wong and Steven Yeun in a story of murder, sex, kidnapping and Asian-American family values

- Ali Wong plays a successful entrepreneur and Steven Yeun a struggling contractor, both living in Los Angeles but leading totally different lives

- Each is trying, unsuccessfully, to impress their Asian-American parents or in-laws; fate, and an unlikely series of events, push them closer together

Actions have consequences. Some are unintended: those of, for example, a road-rage tiff, which escalates into murder, kidnapping, ransom demands, arson, extramarital sex, divorce, potential suicide and rice cookers stuffed with cash.

Ultimately, all this seems to happen in Beef (Netflix) because of a nagging, subconscious desire among Asian-Americans to please grouchy, disapproving parents unsure of how to ensure the best for their children in a culture that they – the parents – can’t or won’t understand.

But don’t let any of that put you off this riotous, 10-part, irony-laden, black-comedy drama, starring Ali Wong and Steven Yeun as residents of Los Angeles, who live galaxies apart economically and socially.

Wong plays successful “lifestyle entrepreneur” and fancy flower shop owner Amy, soon to come into considerable wealth. Yeun is struggling contractor Danny, long-term motel occupant, guardian of younger brother and video-game addict Paul (Young Mazino) and reluctant partner in potential crime of violently unhinged cousin Isaac (David Choe).

Danny, desperate for their approval, wants to build his sceptical parents a house in the hills. Amy, patron of her sculptor husband, who creates expensive, tacky vases, unfailingly appals her terminally dissatisfied mother-in-law. Thus, Amy and Danny both flounder frequently on the roiling seas of Chinese, Korean or Japanese family disapproval.

Beef also skewers the cod philosophies of wealthy Angelenos who live in houses big enough to contain museums; whose children attend “organic gardening playgroups”; who pay actual money for bad-art blobs; and who think haute cuisine mushroom foam is an essential food. (For balance, burger-joint devotees are also roasted.)

10 reasons why Evil Dead Rise is the best film in the horror franchise

As it careers towards a resolution of everyone’s problems, it does, however, sacrifice some credibility, an increasingly unlikely series of events pushing Amy and Danny towards redemption or catastrophe. Such is the cul-de-sac into which road rage may lead. Never mind driving safely – drive courteously.

Busting crime part-time

Detectives are so ineffectual at their jobs that they need help from amateur sleuths. This is a television rule, so it must be true. (Even Poirot was in semi-retirement when he worked many of his wonders.)

But that doesn’t mean just anybody can turn their hand to a bit of crime-busting, even if they, too, are retiring and don’t fancy a prolonged spot of gardening. On the evidence of eight-part series Harry Wild (BBC First), ex-professors of literature should think twice before swapping chapter and verse for mean streets and worse.

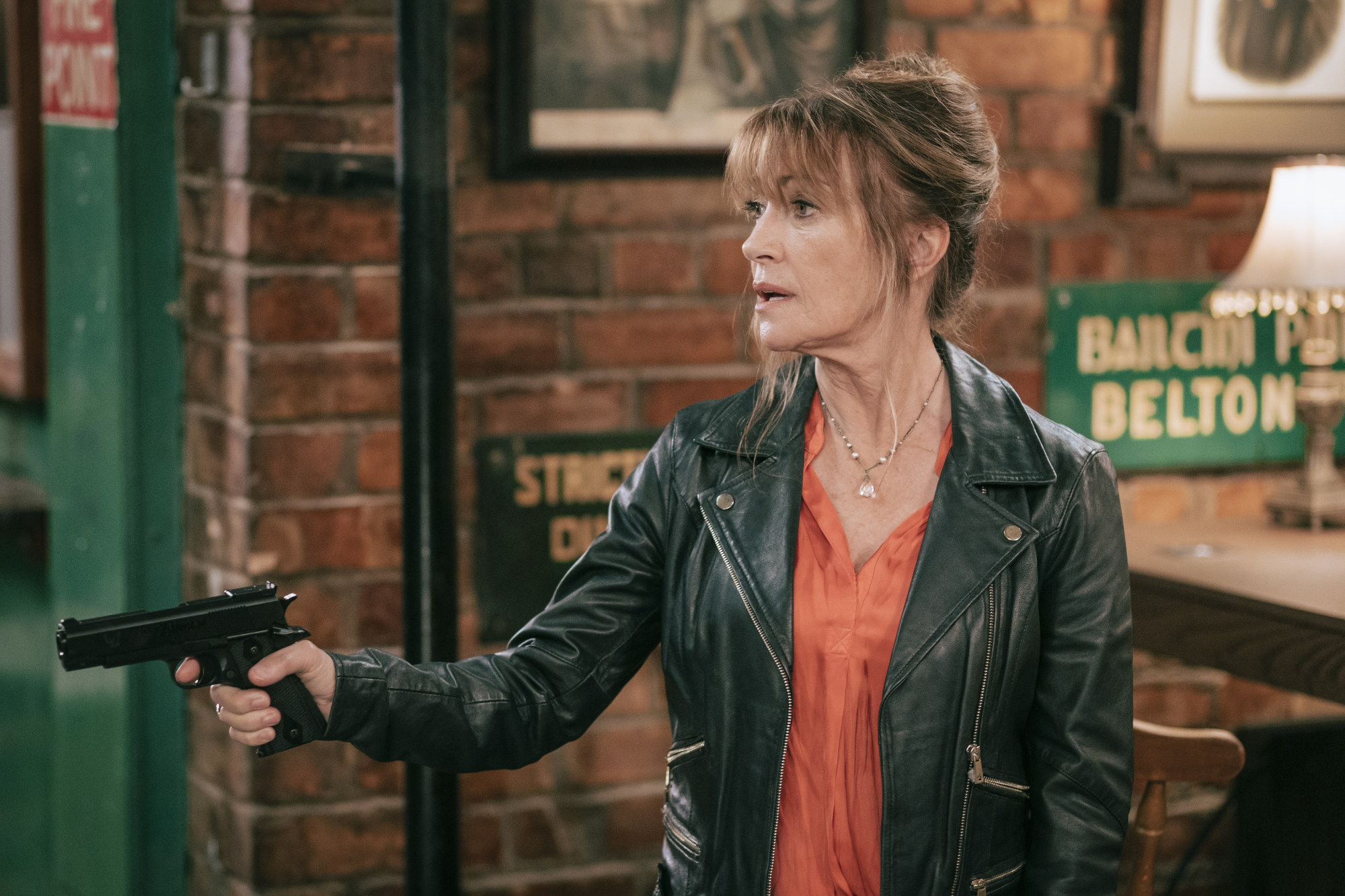

Wild by name and wild by nature, Dublin-based Harriet “Harry” Wild (Jane Seymour), aimless since leaving her job, is mugged. Recovering at the home of her detective son Charlie (Kevin Ryan), the acerbic, confrontational Wild starts meddling in cases and offering the unimpressed Charlie her help.

Suspension of viewer disbelief now becomes paramount. Where the police and their considerable resources fail, Wild steps in to identify unlikely leads, provide suspects and solve cases … based on her reading of books featuring vaguely similar crimes.

Ritual murder, serial killers, even echoes of the fiendish tests in Squid Game can’t compete with Wild’s enthusiasm for her accidental hobby – irritating though it is to those around her.

Equally unbelievably, she finds herself in cahoots with a strange confrère, namely her young attacker, Fergus (Rohan Nedd), whose potential for smart detective work she encourages, rather than his potential for juvenile detention.

Nedd is an accomplished scene stealer, as is Paul Tylak as daydreaming fantasist Glenn, ever ready to puncture pomposity with his tangential, philosophical observations on the quotidian. And frankly, Seymour needs both: the series may have been written for her, but it’s too heavy a tome for the ex-Bond girl to carry alone.