Review | A murder in Toronto and the dark side of the Asian immigrant dream

Jennifer Pan appeared to be the successful child of Chinese-Vietnamese refugee parents but when her gilded story began to unravel she hired hitmen to kill them. Jeremy Grimaldi investigates how seemingly decent people can do dreadful things

A Daughter’s Deadly Deception

by Jeremy Grimaldi

Dundurn

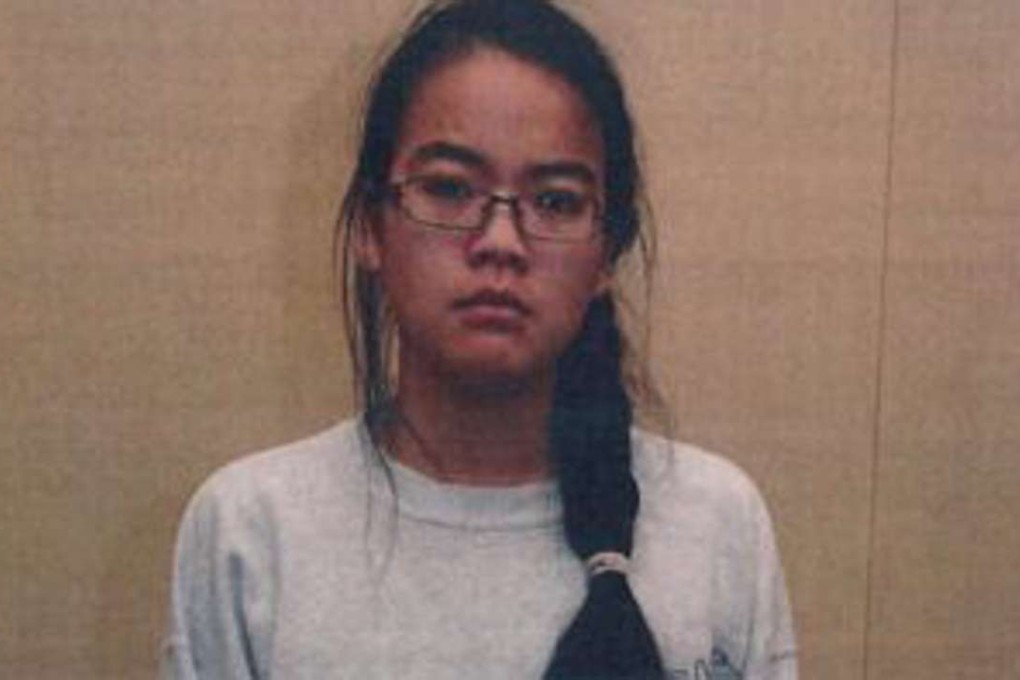

In 2010, a young Canadian woman named Jennifer Pan hired hitmen to fake a break-in at her family home and shoot her parents.

Her father, Huei Hann, saved himself by dragging his bleeding body onto the front lawn. Her mother, Bich Ha, died on the spot, but not before begging for her daughter to be spared. Little did she know that Jennifer was sitting upstairs, listening to the screams as the crime she had masterminded unfolded.

Many readers who pick up A Daughter’s Deadly Deception, by Canadian journalist Jeremy Grimaldi, will be aware of the high-profile case on which the book is based. News of the murder sent shockwaves across Canada and the Asian diaspora, in large part because the assault seemed so unlikely. The crime took place in the comfortable Toronto suburb of Markham, which has a large Asian population. The victims were hardworking ethnic Chinese immigrants from Vietnam, relaxing at home on a quiet Monday night.

The main suspect turned out to be their polite, bespectacled, 24-year-old daughter – an accomplished student, athlete and musician who blamed her mental breakdown on years of extreme parental pressure.