Internet whizz Yat Siu on programming at 13 and landing a job at Atari as a schoolboy

The online pioneer talks about growing up in Austria, launching Hong Kong’s first internet provider and why the education system is failing to prepare students for the age of robots and artificial intelligence

HOME COMPUTING I was born and raised in Austria. English is the language I use for business but German is my mother tongue. My father came from Hong Kong and my mother’s family was from Taiwan, although she was born in Lisbon, Portugal. My parents both studied music in Vienna. I had rigorous classical music training growing up and piano is my main instrument.

My parents were always fascinated with new technology and really attuned to whatever gadgets were available at the time. They would come to Hong Kong and fly back to Vienna with the latest watches and electric toys. We were not wealthy but my parents insisted on having satellite television before anyone else in the neighbourhood, so they could get news from all over the world. I grew up absorbing global culture.

My parents have been divorced for a long time and my mother toured regularly as a professional singer. I was pretty free to do anything I liked outside school and my home became the social centre of the area – all the kids would come over to play. Around 1980, I received my first computer. It was by Texas Instruments. I learned how to programme in Basic and ended up putting a lot of stuff online. Back then it was via bulletin boards and shared through FidoNet. I was 13 or 14 years old.

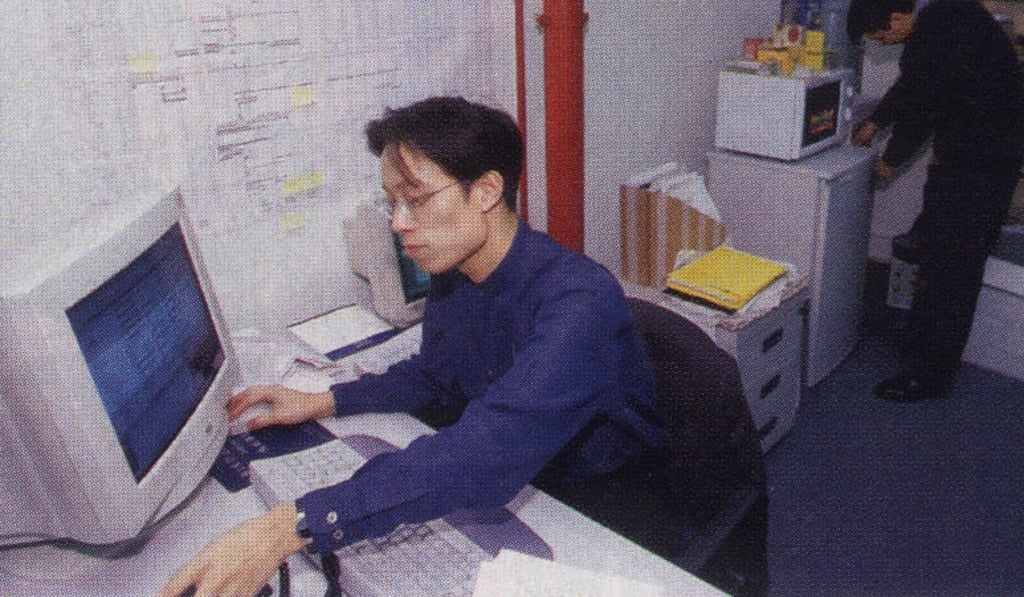

STARTING UP YOUNG Back in the 1980s, there were hardly any programmers so I got a job with Atari (the early arcade and computer games company), which had an office in Vienna. I was still at school. Then, they sent me to the United States, to get some proper computing training. I went to Worcester Polytechnic Institute initially and, later, Boston University. Halfway through my studies Atari went bankrupt, so a bunch of us ex-Atari guys started a business to service and upgrade Atari computers for the brand’s die-hard fans. With the same group of people I later designed graphics software for Silicon Graphics (SGI), which eventually took over our company and hired me as a trainer for their Asia operations.

PUTTING HONG KONG ONLINE By 1995, I had decided I wanted to try something new. I was sent to Hong Kong by SGI and discovered I couldn’t access any internet service. So I quit my job and started the city’s first internet service provider, called HKOnline. I lived in Tin Shui Wai and my rent was something like HK$2,500 a month. The office was in the Hong Kong Industrial Centre, in Cheung Sha Wan, a rabbit warren of fashion outlets that was basic but cheap, and close to the Sham Shui Po computer centre, where we bought all our equipment.