China’s one-child policy has a legacy of bereaved parents facing humiliation and despair

A generation burdened with hunger, a lack of education and enforced family planning must now also face the plight of those who lost their only offspring and the emotional, social and financial consequences that entails

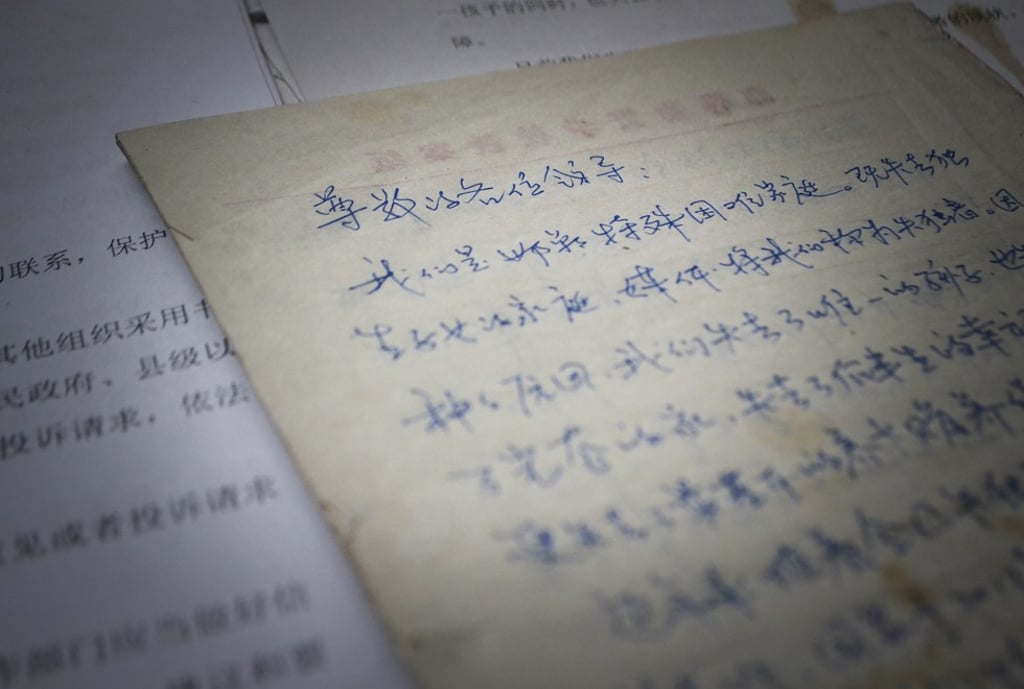

“Both my husband and I were youths in Mao Zedong’s era,” says 63-year-old Wang Aiying. “We abided by the Party’s words, answered the Party’s call of duty and supported the Party’s policy.” Among other things, that meant adhering to the one-child ruling, an act of obedience that would, in 2015, leave Wang in deep despair. After her son died, she became a shidu fumu, one of a growing number of bereaved Chinese entering their twilight years without the emotional and financial support of a child.

Her son, Chang Jia, was nearly not born at all. In 1980, having been pregnant for just a few weeks, Wang, who had previously suffered a miscarriage and wasn’t taking any chances this time around, was in hospital when managers from her place of work came to visit. She had not been given approval by her employer, the Yu Opera House, in Handan, Hebei province, to have a child, they said. “They told me that it wasn’t my turn,” says Wang. “‘What?’ I said. ‘What do you think this is? That I can return the goods?’”

Wang, 26 at the time, successfully argued for the right to have her baby, but after the birth of her son, she was asked by her employer not to have a second child. She agreed and received a certificate for having just one child. “I felt honoured back then, because I listened to the words of the Party,” says Wang. Having five siblings herself, she accepted that the one-child policy was for the greater good and that young people should follow its guidelines.

In 2012, Chang was diagnosed with liver cancer. He did not respond to treatment and, two years ago, he died, at the age of 35. Wang was distraught and she is now childless. She and her husband, who were both laid off before retirement age, were suddenly facing old age without support from the next generation.

Shortly after her son died, Wang applied for the 3,000 yuan retirement subsidy available to one-child parents but she encountered many obstacles. Because she had been laid off, in 2003, she was told she was not qualified for the retirement subsidy. “I don’t have money, nor do I have my son,” says Wang, weeping. “Why did I need to go here and there for all kinds of approvals to get the subsidy?”