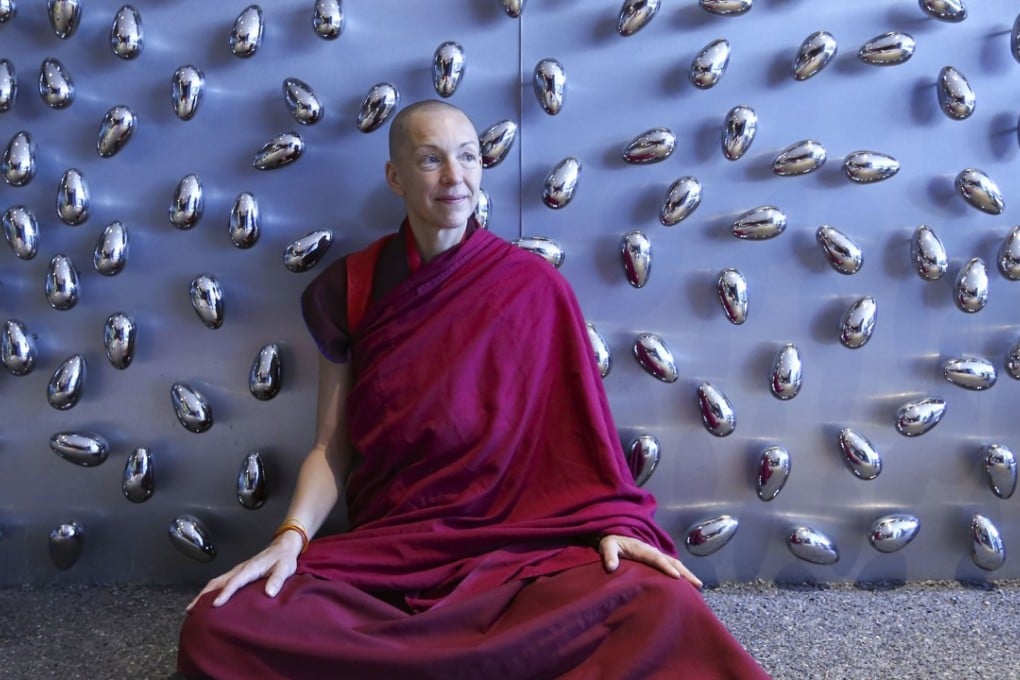

Hong Kong banker turned Buddhist nun on how being held at gunpoint in Indonesia changed her life

Emma Slade, who splits her time between Britain and Bhutan, recalls the trauma of being held hostage in a Jakarta hotel room and reveals how, having spent five years in robes, she balances motherhood and monastic practice

From Kent to college I was born in Whitstable (southeast England) in 1966, the eldest of three. My childhood was quite traditional: Dad earned the money; Mum stayed home and cooked the fish fingers. It wasn’t demonstrative or emotionally verbal. I’m always telling my son, Oscar, 11, I love him and that he’s fantastic.

By the age of nine I was very tall so always felt slightly odd; socially, I wasn’t very confident. At 16, I changed to a boarding school. The teachers thought I should aim for Oxford or Cambridge and I got offered a place at Cambridge to study English. (Slade switched courses, then dropped out, worked in a supermarket, then returned to complete a foundation course in art.) I then got a place on a fine art degree course at Goldsmiths college, in London. Towards the end of my three-year course, Mum told me Dad had been diagnosed with lung cancer.

I expected to hate Hong Kong but I didn’t; it has extraordinary energy

The road to Hong Kong I’ve had trauma, I’ve overcome trauma, and it’s been incredibly helpful for me to go through that. The first real shock was the death of my father when I was 26. When I was 10 or 11, my Dad had said he could see me going into investment banking. Until his illness I imagined I would be an artist or a curator. But, with his death, I could not continue with that plan. I needed to make sure I could make a living and not lean on Mum.

I first arrived in Hong Kong in 1995 as part of the graduate programme of a global bank. I expected to hate Hong Kong but I didn’t; it has extraordinary energy and doesn’t procrastinate.

It had a start when I opened the door to him, and then there was the (three hours) in the room with him. Then it had a finish when I decided I was going to run. It was ghastly, but it had a start, middle and end. But the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) arose without me realising and just got worse.