The Nanking massacre: why Hong Kong and world downplayed atrocity, distracted by New Year’s Eve partying and a minor incident

Few in the colony or elsewhere knew or cared about the horrors being unleashed on civilians in the former Chinese capital by Japanese troops; only decades later did the true scale of the atrocities receive widespread publicity

This weekend, the Nanking massacre memorial complex, in the western suburbs of the former Chinese capital now called Nanjing, will be even more crowded than usual, as tens of thousands of people descend on the site to mark the 80th anniversary of the bloody tragedy that occurred over a seven-week period during the winter of 1937-38.

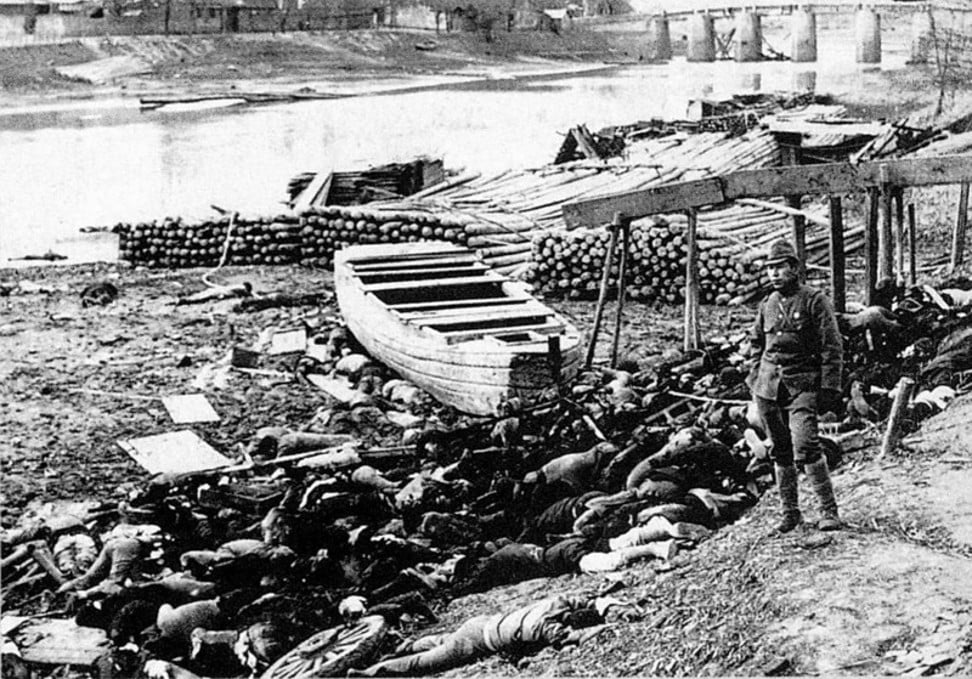

With the possible exception of the Nazi holocaust and the detonation of two atomic bombs over Japan, the sacking of Nanking was perhaps the most egregious human atrocity of the second world war; yet 80 years ago, few people outside the devastated city were aware of its horrific scale.

“There was a general feeling that what had happened was bad, but the event was very far from having the iconic stature that it has attained in recent decades,” says Peter Harmsen, author of Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City (2015).

There is a core of inexplicable horror attached to events such as the Nanjing massacre

By New Year’s Eve, the Westerners who administrated the International Safety Zone (or refugee zone), a 3.86 square kilometre area centred on the US embassy that included 25 camps for civilians, were shocked and drained. They estimated that about 200,000 terrified people were sheltering inside this small district by the end of 1937.

“I could go on for pages telling of cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief,” wrote Dr Robert Wilson in a letter to his wife, on December 15.

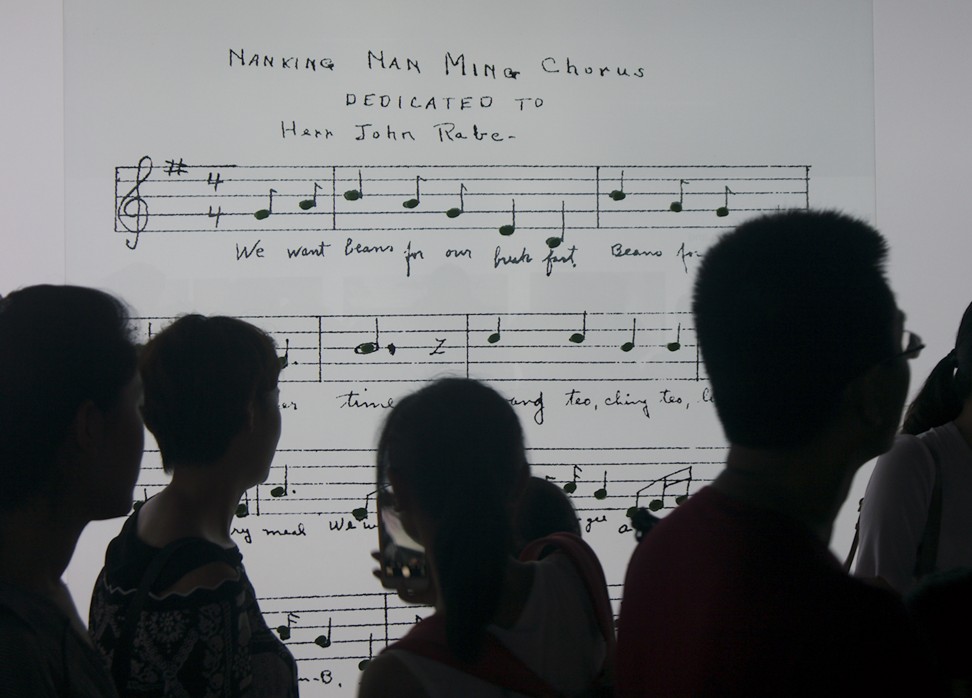

“All 27 Westerners [including three journalists who would soon leave] in the city at that time and our Chinese population were totally surprised by the reign of robbery, raping and killing initiated by your soldiers on the 14th,” John Rabe, a German businessman, declared in a letter to the Japanese embassy on December 17.

“They kept a record, without which we could not write the history of the massacre with as much detail as we can today,” says Timothy Brook, professor of Chinese history at the University of British Columbia and author of Documents on the Rape of Nanking (1999), a chilling compilation of evidence describing the atrocity.

“The old year was swamped under the maddest and merriest reception a New Year has ever received,” gushed the front-page of the Hong Kong Daily Press on January 1, 1938, and it is unlikely that events in Nanking formed any part of the desultory chit chat enjoyed by the “joyous crowd” at parties across the colony.

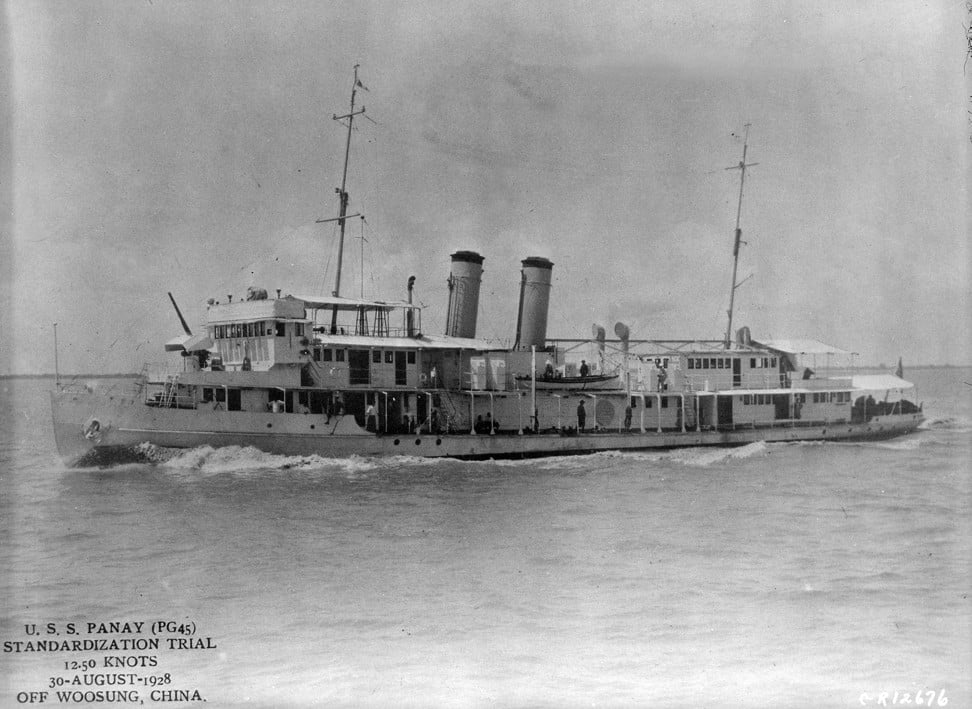

Instead, it was the Panay Incident that captured public attention in Hong Kong.

The USS Panay was a shallow-draft American Yangtze river patrol vessel under the command of Lieutenant Commander James J. Hughes. The ship’s company of 54 was engaged in rescuing embassy staff and expatriate civilians, including several journalists, evacuating Nanking. On December 12, as the vessel sailed upstream escorting three Standard Oil tankers, Japanese planes were spotted overhead by lookouts.

After some 50 minutes, the ship’s company were forced to abandon their crippled vessel and witness it sink in the shallow, murky waters from the shelter of a small reedy island. Storekeeper First Class Charles L. Ensminger and Italian reporter Sandro Sandri were killed in the attack, and coxswain Edgar C. Hulsebus died later that night. Forty three sailors and five civilians were wounded.

The sinking of the Panay caused more of an uproar in the US than all the wholesale rape and slaughter in Nanking combined

The film caused public outrage when it was released in the US and president Franklin D. Roosevelt requested the cutting of the most outrageous scenes, to reduce the risk of his country being dragged into war with Japan, four years before Pearl Harbor.

“The sinking of the Panay caused more of an uproar in the US than all the wholesale rape and slaughter in Nanking combined,” writes the late Iris Chang in her seminal book, The Rape of Nanking (1997), and the reaction in English-speaking Hong Kong was comparable.

Despite the three American journalists who left the city on December 15 filing their accounts, by the end of 1937 the world had little idea of the scale of the atrocities. “The news got out, and was picked up by Western newspapers,” says Brook, but the stories were often dismissed or ignored.

The Panay Incident and Japanese propaganda dominated reports from Nanking well into January. On January 13, a report in the Post told of a collection taken in Tokyo for the Panay survivors being refused by the US ambassador, Joseph Grew. On January 19, it was reported that Italian Luigi Barzini, another journalist on board the Panay when it sank, had given his account of the incident to a packed audience at the Hong Kong Rotary Club.

And Hong Kong had more cultural and commercial connections with Shanghai, which had its own humanitarian disasters to contend with. On January 17, the Post published a story under the headline “Ugly Incidents in Shanghai – Japanese involved”. In Hong Kong, as elsewhere, the greatest atrocity in modern Chinese history was lost in the noise of war.

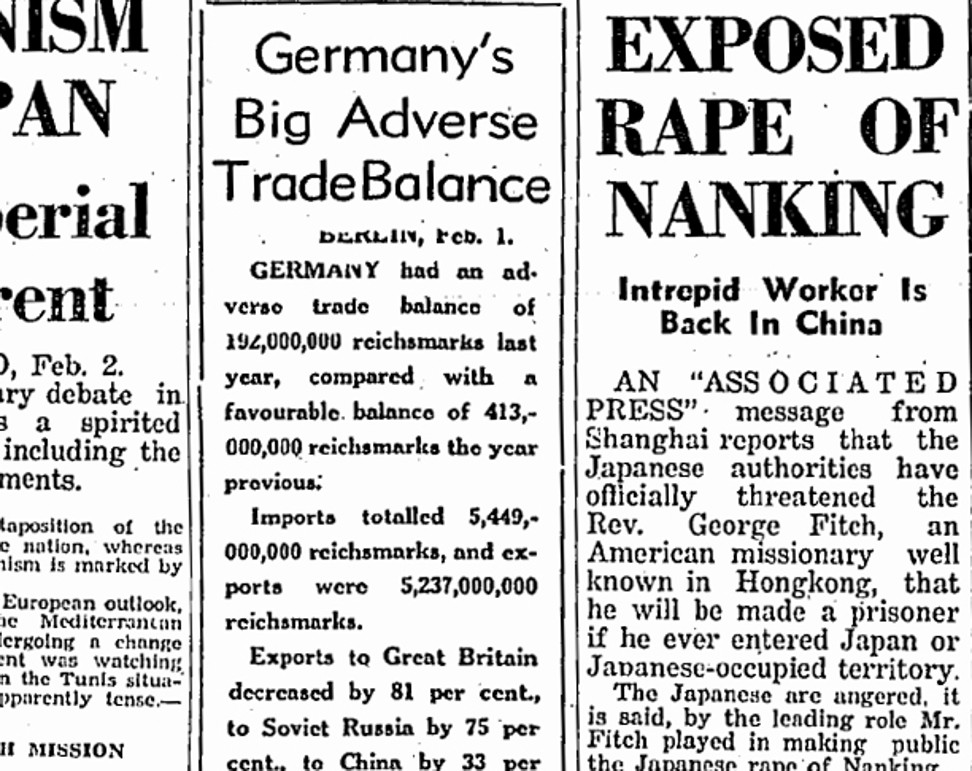

It was on January 28 that the China Mail ran the headline “Rape of Nanking”, the first time the phrase had been used in Hong Kong. It was probably coined by one of the three American journalists who left Nanking for Shanghai on December 15, or by the Manchester Guardian reporter Harold J. Timperley, who is credited with running one of the first accurate portrayals of events in Nanking. But, even as more news leaked out, the story failed to make the proper impact and Chiang Kai-shek did not use the events as a propaganda tool to win more support from the West.

It wasn’t until 1939 that Chinese political scientist Hsu Shuhsi compiled the documents of the Westerners of the International Rescue Zone Committee, and only after the war that newsreel footage taken inside the city walls and photographic evidence was made widely available. Yet even then the Nanking massacre didn’t attain anything like the profile of other major wartime catastrophes. People in Asia were weary of conflict and the interminable stories of torture and brutality, and those in China were immediately engaged in a bitter civil war.

Chang points out that after 1949, both Taiwan and the new People’s Republic of China had to compete for the favour of Japan as a trading partner to rebuild their ruined economies. The West was anxious to embrace Japan as an ally in the developing cold war. And “the communist regime after 1949 seized on the Nanking massacre as an example where arch rival Chiang Kai-shek had failed as leader, abandoning tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians to a sinister fate”, Brook says.

It was in no one’s interest to make a big fuss about the massacre or confront Japan over its continued denial of events.

“All of which reminds us that, for official China, history is a game you play in order to prove that you were right all along, which makes for poor history,” Brook says.

It may have been widely ignored at the time in Hong Kong and exploited and denied over the years, but thanks to the efforts of those few Westerners who remained, the awful truth cannot be buried.

“There is a core of inexplicable horror attached to events such as the Nanjing massacre,” says Harmsen, “which says something deep and sinister about human nature and about our propensity to inflict pain on fellow human beings because we can and because we like it.”