Back in Hong Kong home from where Japanese took his father for execution, British scientist is ‘very emotional’

Dr Jim Flegg, ornithologist who was guest of honour at recent eco-education event, steps inside his former Hong Kong home for the first time since he was a child and wartime evacuation to Australia heralded a life steeped in nature

His wide-ranging scientific expertise made Dr Jim Flegg the ideal guest of honour at November’s Tai Tam BioBlitz. A prolific writer, broadcaster, speaker and television personality, and the recipient of an OBE in 1997 for his services to horticulture (although it could equally have been for his work as an ornithologist), it would have been hard to find a better fit for the event, in which teams work together to discover and identify as many species of plants, animals, microbes and fungi as they can.

For the British octogenarian, a compelling personal connection made this a special event: it was literally a homecoming, to a place where he had spent the first three years of his life.

Jim’s father, Jack Sydney Flegg, was the engineer in charge of the pumping station that drew water from the Tai Tam reservoir, up beside the road between the city of Hong Kong and what was then the tiny village of Stanley. Accommodation in the Tai Tam Tuk senior staff quarters came with the job, which was to manage the sizeable crews involved in operating and maintaining the reservoirs, dams, aqueducts and tunnels. Despite the grand sounding name, the quarters, completed in 1905, comprised a two-storey, box-shaped cottage constructed on a platform perched above Tai Tam Bay, east of the main pumping house.

One of the few recollections Flegg has of his early years is of floating in a breeches buoy just off the stony beach immediately below the house while visitors swam around his father’s yacht, High Heels. He remembers a police launch coming into the bay on patrol and he recalls stuffing leaves into the muzzle of Teddy, the family’s long-suffering pet Chow. He has no memory of tumbling down the steps between the main entrance to the house and the path leading to the pumping station. In later years, Flegg’s mother would narrate this horrifying episode along with descriptions of the family car, a 1933 Austin 7 Ruby saloon, the slimmest vehicle available and virtually the only one able to negotiate the narrow road to Stanley where it ran along the top of the Tai Tam dam.

Among a handful of precious photographs, Flegg has a picture of himself with his amah. He says he was aware of speaking Chinese although nothing has stayed with him beyond the Cantonese for “aeroplane”, “windscreen wiper” and “hurry up!”

“Cantonese was probably my first language in those days as the cook, my amah and various junior engineers, stokers and mechanics were all Chinese,” he says, when we meet in the Excelsior Hotel coffee shop, in Causeway Bay.

Both sets of Flegg’s grandparents lived in Hong Kong from the 1920s, as civil servants attached to the Admiralty.

“My father arrived in 1920, at the age of 13, and my mother arrived with her parents in 1926, when she was aged 16. My mother taught herself shorthand and typing and worked as PA to the executive secretary of the Hong Kong Jockey Club, based at Happy Valley.

“Both families lived in Nathan Road and they enjoyed the typical expatriate social lifestyle: a hectic round of horse racing, tennis and swimming parties. My parents met in Hong Kong in 1928 and got engaged in November 1929; they were married in 1933, in Gillingham, Kent.”

I have no horrific memories of the occasion – but I do recall ‘God bless Daddy’ in my bedtime prayers each evening

Flegg’s maternal grandparents had retired to Gillingham in 1930, and his father’s parents returned to England in 1932, on the P&O liner Rawalpindi.

Jim Flegg was born on April 23, 1937, at the British Military Hospital, on Bowen Road. A few weeks after his birth he was baptised James John Maitland Flegg in St John’s Cathedral.

One of Flegg’s earliest recollections is of “creating an awful fuss at having to wear a toddler’s gas mask (piggy face)” when the family went on leave to Britain, probably in 1939. War was approaching and the Fleggs were soon back at sea, en route to Hong Kong. And little Jim and his mother would soon be on the move again, as part of the evacuation of women and children ahead of the anticipated Japanese invasion.

It would be another 77 years before he stayed again in the cottage at Tai Tam Tuk.

The first port of call for the evacuees from Hong Kong was Manila, where they were transferred to Baguio for a short stay in the cooler hills before embarking for the onward journey to Sydney, Australia. In the Philippines, Jim was diagnosed with suspected pneumonia and sent to Manila’s American Military Hospital.

“According to my mother, the nurses were far keener to care for military men than children, and I was given a supply of sulfa drugs (then the latest medicine available to American soldiers) and packed off back to the ship. We continued to sail south, making landfall in daylight in Sydney Harbour, where I remember sailing under the spectacular bridge. We were then dispersed in groups to temporary accommodation.”

Flegg and his mother were soon transferred south, to Melbourne, where they lived with other Hong Kong evacuees in a flat block on Queens Road. Funds from Hong Kong ceased soon after the colony fell to the Japanese on Christmas Day, 1941, so the British government provided money for the evacuees.

“It must have been while we were at Queens Road that the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour [on December 7, 1941]. Australians were extremely anxious about an invasion, with all the able-bodied menfolk away fighting and just six fighter aircraft for defence. Darwin was bombed by Japanese warplanes,” Flegg says. “This much we knew from radio bulletins, but what we were not to know until about nine months later were any details of the attack on Hong Kong or of any casualties.”

Flegg’s father was a staff sergeant in the Royal Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Force, in charge of a detachment of elderly armoured cars.

When Japanese soldiers swarmed across Hong Kong Island, so far as Arthur Clarke (Flegg’s godfather and a pre-war family friend who would become financial secretary of Hong Kong in the 1950s) was able to piece the story together after the war, Flegg’s father and those staff at Tai Tam who remained loyal were taken more or less immediately to the beach below the house and shot.

The Yarra was shallow and sluggish, and even kids could catch the crayfish [yabbies], though we never cooked any. The beach at St Kilda could be idyllic or very rough, when the sand blew and stung

“Though the news of the fall of Hong Kong on Christmas Day was known worldwide soon after the event, it was not until some eight or nine months later that the Red Cross obtained details of casualties and of those interned in prison camps in Hong Kong. In our group of evacuees, my father was the only fatality,” Flegg says. “It is a tribute to my mother, and to the others around us that, although I must have been told, it was done in such a way that I have no horrific memories of the occasion – but I do recall ‘God bless Daddy’ in my bedtime prayers each evening. At that age, I have no doubt that memories dimmed swiftly to be replaced by the urgencies, changes and excitements of daily life.”

The evacuee groups began to separate although they remained in touch. Flegg’s mother became residential housekeeper to a family named White, who ran a laundry in Melbourne.

“The business was run by the wife while the husband was away fighting. They had a friendly teenage son, Roy, who occasionally took me to the laundry with its huge boilers, masses of suds and ironing boards. Soon after, the threat to Australian cities was perceived as intensifying, and many residents moved out to the surrounding and less threatened townships. Mother and I, and [fellow evacuees] Mary Wilson and John, moved to Bendigo, but only for a short while.

“I have two abiding memories of Bendigo,” Flegg says, of the town in central Victoria. “The first is of my mother and Auntie Mary digging with crowbar, pickaxe and spade an air raid shelter, a few feet long and deep, roofed with corrugated iron sheets – fortunately never called into use. The second was of a conical, very green hill in the distance at the bottom of our road, to which we once walked to have a picnic. Sadly, when we got there, the grass was nothing like as green, and the ‘hill’ turned out to be a mining spoil heap of very knobbly rubble. Such was life!”

The Fleggs returned to Melbourne, to the suburb of West Malvern, where his mother became resident housekeeper to another family. Flegg has fond memories of the 100-year-old family homestead, a rambling timber-framed, timber-clad bungalow surrounded by a large veranda.

“It was an absolutely wonderful place for a moderately free-range youngster, with tree camps and ample opportunity, with local friends, to get lifts [by truck or more often by horse-drawn cart] into the surrounding countryside, which quickly became bush. Most of the time we wore only sandals and shorts; shirts rarely. The ‘fridge’ was an ice chest, chilled by a huge block of ice in a zinc tank, which was replenished every so often from a horse-drawn ice cart. Milk also came by horse-drawn cart; the horse wore rubber shoes for quietness. The milkman allowed me to ‘drive’ [hold the reins] along our road.”

At the age of five, Flegg was enrolled in primary school in Melbourne, to which he travelled, often unaccompanied, by tram. He remembers struggling with his letters using a slate and recalls that “geography focused on seas and sharks, the Great Barrier Reef, and the terrors of bush fires in the huge arid interior. History ran from the colonisation of Botany Bay, and thus Sydney, by settlers and convicts, and totally ignored the Aborigine tribes, which were considered (a) primitive and (b) untrustworthy, even dangerous, in isolated areas. After that, it was the exploration of the arid interior in the 1800s and particularly the south-north crossing to what is now Darwin.”

He played in gardens and took trips to the park by the Yarra River in central Melbourne or to the beach at St Kilda.

“The Yarra was shallow and sluggish, and even kids could catch the crayfish [yabbies], though we never cooked any. The beach at St Kilda could be idyllic or very rough, when the sand blew and stung. There were occasional shark alerts, usually grey nurse it was said, but whatever, it put the fear of God into kids. Throughout our years in Australia there were occasional excursions, long weekends to nature reserves like Ferntree Gully, where I can remember my first wild orchids and torrential rain, and Sherbrooke Forest, where we tracked down my first lyrebird – which turned out to be life-changing in what it triggered.”

As the war in Europe was coming to a close and, in the Pacific, the Japanese were struggling for survival, the conditions were deemed appropriate to repatriate the evacuees. Those who, like the Fleggs, elected to return to Britain left first, the Hong Kong-bound group having to wait until the colony had been liberated.

Around his eighth birthday, in 1945, Flegg and his mother boarded the SS Akaroa; as before, they were restricted to only one cabin trunk and one suitcase. The voyage had an exciting start as, for the first few days out of Melbourne, the vessel steamed due west across the Great Australian Bight, famously rough year-round and especially so at the start of the (southern) winter.

“The Akaroa was not large, and was cutting obliquely across the massive South Pacific rollers: in consequence, almost everybody was confined to their bunks – we had a cabin but no en suite in those days – until the seasickness passed and ‘sea legs’ were found, usually children first.

“After the Bight, we took a lights-off zigzag course across the southern Indian Ocean towards Cape Town, in South Africa. The zigzags were designed to help avoid torpedoes, as there were still thought to be active Japanese submarines in the area, but these manoeuvres only exacerbated the sudden violent lurches as the Akaroa and rollers came into conflict. This made meals entertaining, as plates, food and cutlery slid across the tables very noisily. There were also regular lifeboat drills and trial firings of the Akaroa’s Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns.

“The mothers organised games and a period of schooling every day, and when we were about on deck, we could see porpoises, whales, sharks and albatrosses. There were also various gulls and terns, and small dark fluttery birds that I now know were petrels, and one black-and-white one sticks firmly enough in my memory for me to be positive that – as the crew told me – they were [the type known as] ‘Mother Carey’s Chickens’.

Departing Cape Town, we headed for St Helena, an isolated colony in the middle of the South Atlantic – the first passenger ship since before the war to do so

“Suddenly, well across the Indian Ocean, the Akaroa ceased to tack and held a straight course – VJ [Victory over Japan] Day had happened after the atom-bombing of Japan. We headed for port lit up at night, the first ship post-war to enter Cape Town with her lights ablaze. From the ship we could see Table Mountain; time did not allow an ascent – we went to the amazing Botanic Gardens instead.

“Departing Cape Town, we headed for St Helena, an isolated colony in the middle of the South Atlantic – the first passenger ship since before the war to do so. St Helena is a small, steep and rocky island, subject to continuous Atlantic swells. Landing was exciting as there was no breakwater, and one of the Akaroa’s boats took us as close to the landing steps as it dared. In a lull in the surf, we jumped ashore and scampered up the steps. I don’t remember life jackets! If we were not quick enough, there were overhead cables and dangling ropes which you grabbed and pulled your knees up to your chest. Most of us children delighted in getting wet.

“Jamestown, the capital, was tiny and on two levels. From the landing, you could trek up the hairpin bends of the road or you could, as we did, go up ‘Jacob’s Ladder’, a very steep flight of several hundred concrete steps. While the ship unloaded its freight from Cape Town, we went on an island tour in an antiquated hearse, suitably modified with more seats. The target was the isolated villa in which Napoleon was incarcerated in exile, and where he died.

“Departing St Helena, we steamed (coal-fired, of course – the kids had a noisy tour of the engine room on the way) northwards for Tilbury Docks. Landfall here would have been ideal for us – just a ferry across the Thames and a short bus or train home to the grandparents in Gillingham. In worsening weather, cold and rainy, we had the news that a dock strike at Tilbury – a regular occurrence in those days – had closed the Port of London and we would land instead at Avonmouth, near Bristol.

“Six or seven weeks after leaving Australia, my first real sight of England was early on a grey morning, nearing Avonmouth, when looking out of our porthole I saw bright green fields and trees, having been used to Australian grey-greens and browns. We disembarked and endured a chilly wait for passport and [intensive] customs clearance, before crossing the quay to a waiting steam train for London, Paddington. We had bought a bag of oranges in Cape Town, which we placed on the luggage rack, attracting disbelieving eyes from fellow passengers” who were still subject to wartime rationing.

Flegg and his mother weathered the two coldest British winters on record and he continued his education at Gillingham Grammar School, leading to his enrolment at Imperial College, London, where he obtained a BSc and a PhD. He started his career as a soil zoologist for East Malling Research Station, where he remained for most of his working life, with the exception of seven years as director of the British Trust for Ornithology.

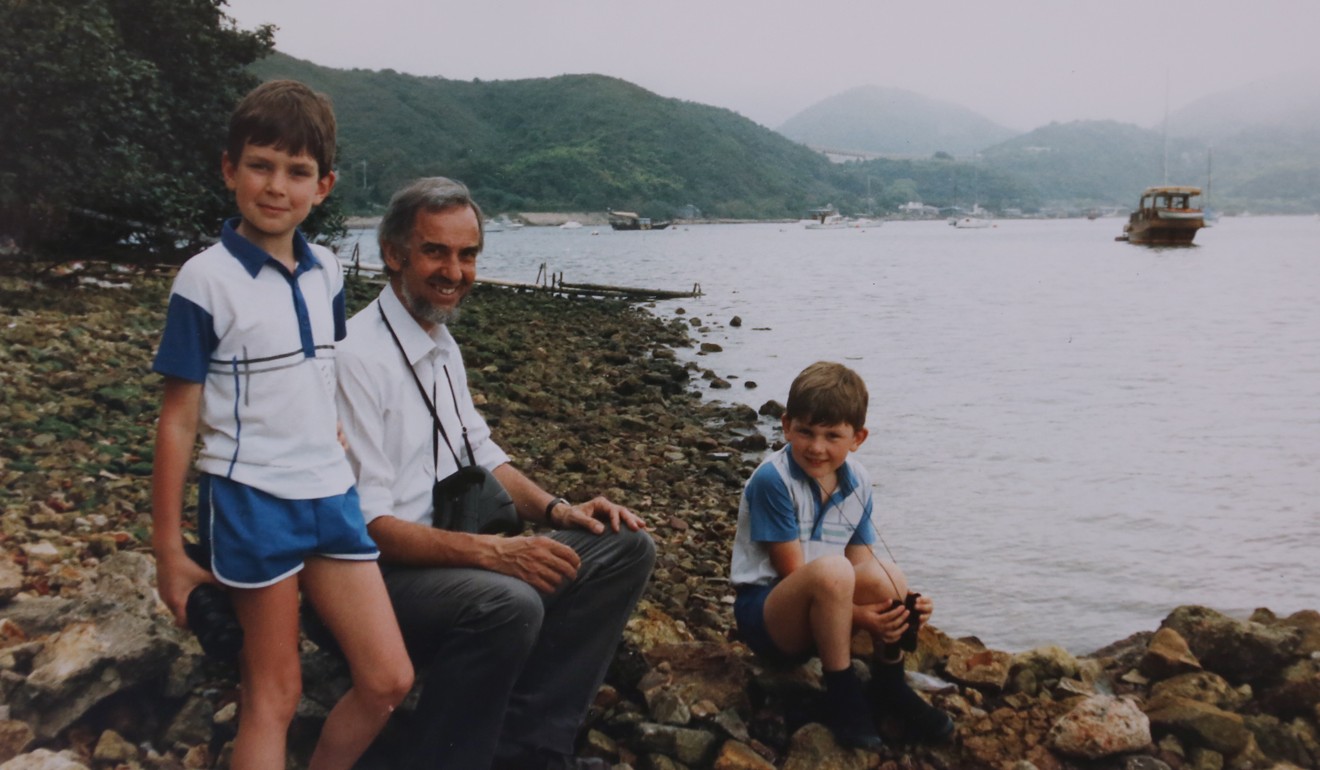

Flegg’s first return to Hong Kong was in 1987, when he turned 50.

“My mother wanted to show me where I was born, where my father was killed and where he was buried.” Jack Flegg is at rest in one of the many “unknown” graves of the Hong Kong Volunteers in the Sai Wan War Cemetery.

“We decided to bring the whole family, our sons then aged eight and six. At that time, the cottage was a hostel for the rehabilitation of heroin addicts run by St Stephen’s Church: it was a very sobering visit. My mother said the house did not seem to have changed much. We walked down the steep path to the beach where my father was killed; a very emotional experience.”

That year, Flegg took part in Hong Kong’s Big Bird Race (a birdwatching event staged by conservation organisation the World Wildlife Fund – now the WWF – to raise funds). At the closing party, Flegg met Michael Lau Wai-neng, then a fresh university graduate.

Our sons have asked many times how one manages without a father to play games with and learn things from. I do choke up when I talk about it

Flegg spotted him as a talent in need of nurturing and they stayed in touch. Today, Lau is the director of wetlands conservation for WWF Hong Kong.

Last year, Lau contacted Flegg in great excitement to say he had met Jenna Ho Marris, who was living in the Tai Tam cottage with her family. A microbiologist turned lawyer (although currently not practising), she is the prime mover behind the Tai Tam Tuk Eco Education Centre and its many-faceted activities, including the recent BioBlitz. Ho Marris invited Flegg and his wife, Caroline, to stay in the cottage during the BioBlitz.

He could never have imagined this happening, he says. Stepping into the house for the first time in some 77 years was “very emotional”, but Flegg had no sense of déjà vu and recognised nothing.

“As I have grown up and had children of my own, I appreciate more and more what I missed, which has probably led to my emotions being stronger. Our sons have asked many times how one manages without a father to play games with and learn things from. I do choke up when I talk about it. Over the years, I realise more and more what my mother [who died in 1998] had to contend with and I obviously owe her a great deal.”

An unexpected bonus for the Fleggs came at the end of the BioBlitz. The Water Supplies Department (WSD) was represented by an assistant director of development, Chau Sai-wai, who, on learning that Flegg had spent his early years at Tai Tam Tuk, took the couple on an impromptu tour of the pumping station, the key part of the Tai Tam raw water collection system. The red-brick building has changed little since it was built, in 1904.

In Jack Flegg’s day, the pump was powered by steam engines fed by coolies shovelling coal into the furnace; then came diesel power and nowadays everything is operated by a computer-controlled electric pump.

In continual use since its completion, this is the WSD’s oldest functioning pumping station. With its 12-metre-high pitched roof, the warehouse-style engine hall is a rare example of historic industrial architecture still functioning for its original purpose. It was declared a monument for conservation in September 2009 as part of the 5km Tai Tam Waterworks Heritage Trail, covering 21 historic structures linking the three reservoirs by dams, aqueducts and tunnels.

“I can’t say I recognised the pumping station, but there was a huge drawing office table, looking virtually unchanged since the 1940s, and probably undusted also!”

Flegg has made seven return trips to Hong Kong and he and his wife are already planning their next visit, which they hope can be timed to coincide with the next big Tai Tam Tuk project.

The Fleggs are full of praise for the BioBlitz, which was attended by more than 360 people – experts and participants who joined guided activities. Ages ranged from two to 80 and more than 500 species, including a seahorse and a spider that might be new to science, were recorded on the day.

“We’ve attended many citizen science projects in the UK,” Flegg says, “but never anything to rival this in scope or expertise.”

With its three reservoirs and tidal inlet, plus the historic village, Tai Tam remains idyllic. A water sports centre, it has substantial tangible and intangible heritage in addition to three sites designated as being of special scientific interest.

Early childhood experience is known to form the adult personality and it seems likely that Flegg’s wide-ranging scientific interests owe more than a little to his younger days in Hong Kong.