Why British-born Chinese comedian swapped poker for writing jokes

More than 85 years after his playwright great-grandfather became a household name in Britain, Ken Cheng is wooing audiences with his own brand of humour … just don’t tell mum and dad

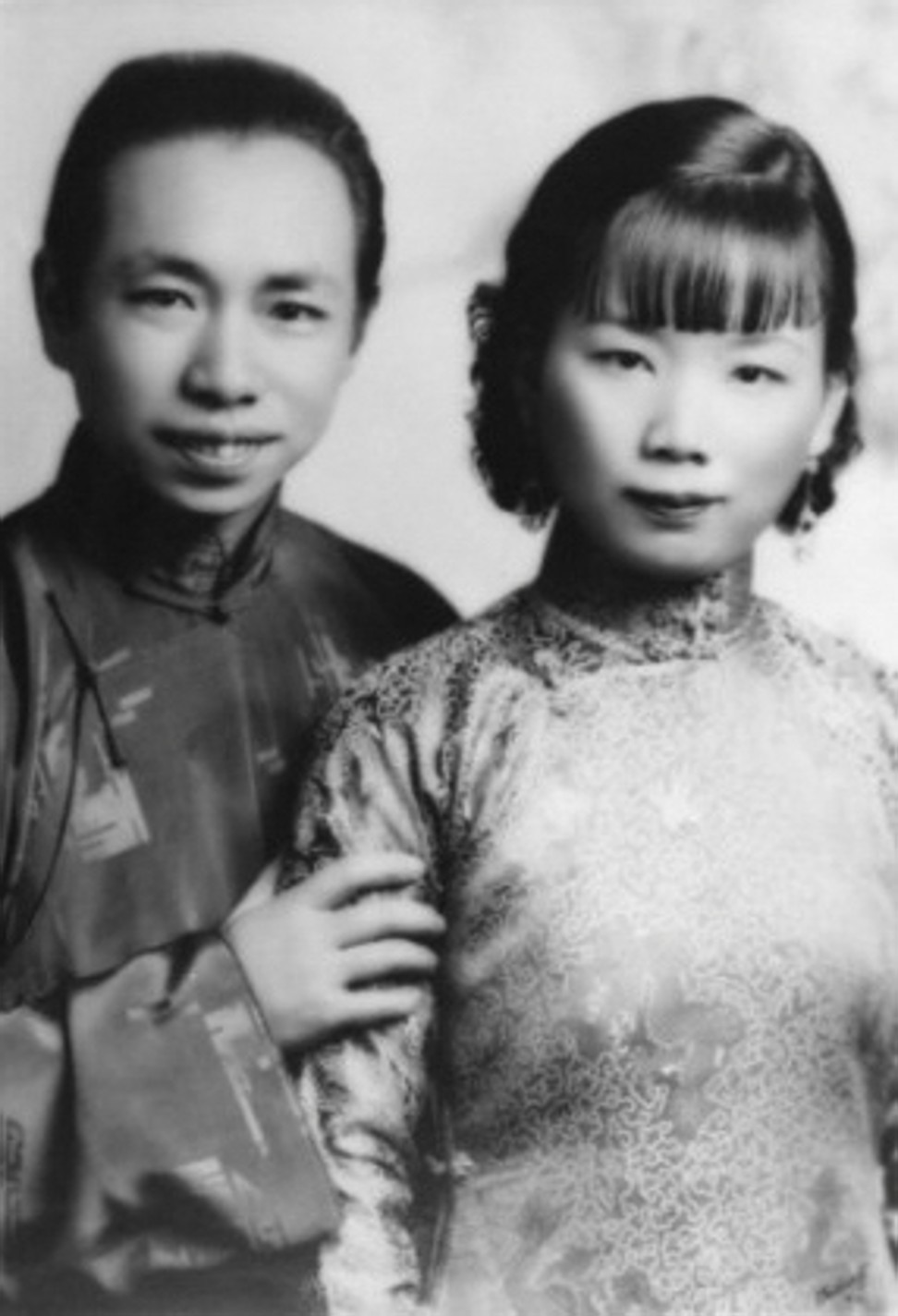

Almost 85 years ago, an unknown postgraduate student morphed into the most celebrated Chinese person in Britain, his play having become an unlikely smash hit. The interpretation of an ancient Peking opera by Hsiung Shih-I – the first Chinese director to work in the West End as well as on Broadway, in the United States – was beloved by the public, literati and royalty alike, and would shape British ideas of Asia for generations to come.

Almost a century on, Hsiung’s great-grandson is wowing British audiences with his own take on Chinese culture. Though, it has to be said, their art forms are slightly different.

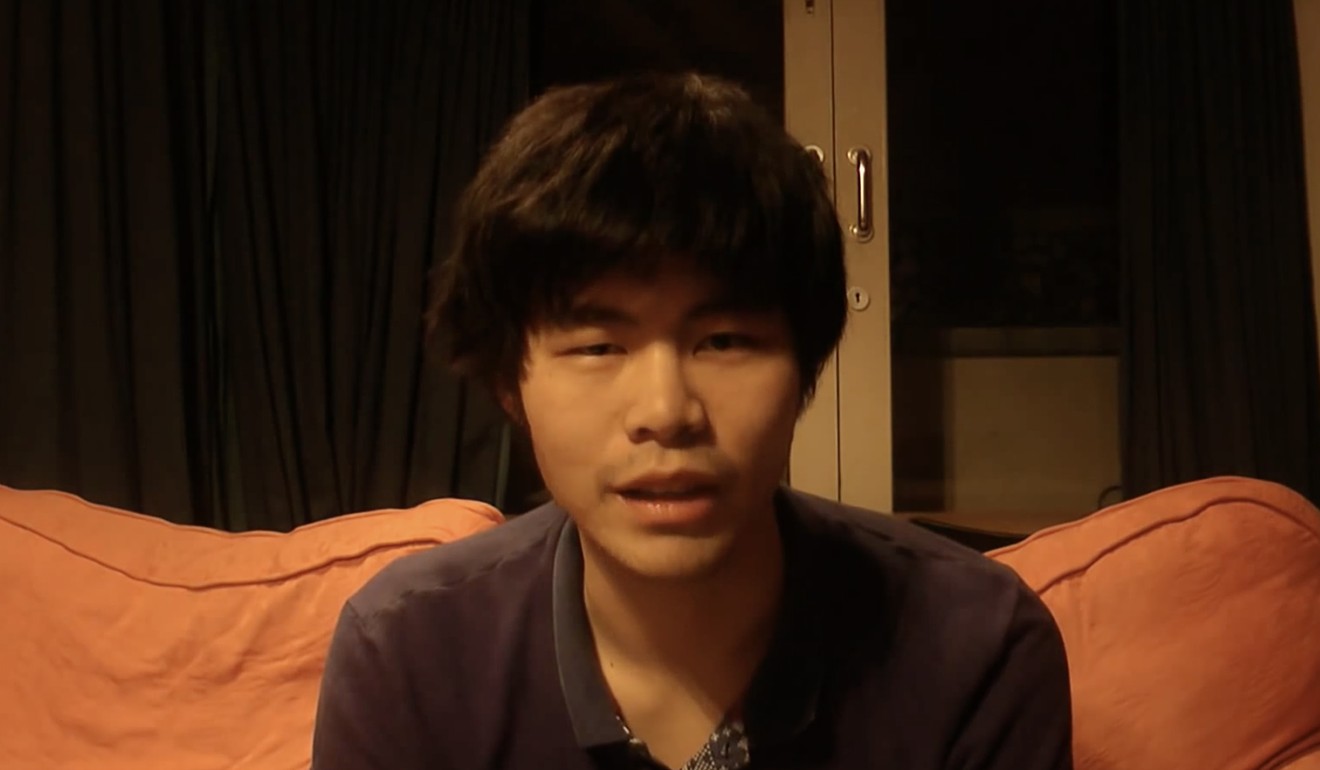

Ken Cheng is a BBC. That could stand for “bloody brilliant comic”, which he is; an award-winning performer who has been hailed by The Scotsman newspaper as “a fiercely accomplished talent”. It also stands for “British-born Chinese”. But it should most certainly not, as one of Cheng’s gags has it, “be confused with the more popular usage of that acronym – ‘big black c**k’”.

The 29-year-old is at pains to make clear that the joke is not part of his set any more. “I don’t know, I just feel like I shouldn’t be saying ‘big black c**k’ as often as I did. I feel like that’s not my brand.”

Whatever his brand is, it will soon be promoted by the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation), just like that of his great-grandfather. Cheng has been commissioned by Radio 4 to produce a four-part series inspired by his first hit comedy show, Ken Cheng: Chinese Comedian, revealing “how his Chinese upbringing in the UK has made his brain so weird”.

Cheng shot to fame last year, when he won the funniest joke award at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, beating comedy veterans including Frankie Boyle, Alexei Sayle, Tim Vine and Ed Byrne. Cheng’s winning one-liner? “I’m not a fan of the new pound coin, but then again, I hate all change.”

He has, in a short space of time, made a name for himself for his abstract wordplay, painfully logical deconstruction of common phrases and ultra-rational take on life.

I don’t let my parents come to my gigs. No! I just am very weird about that. I just can’t have them see me in that light

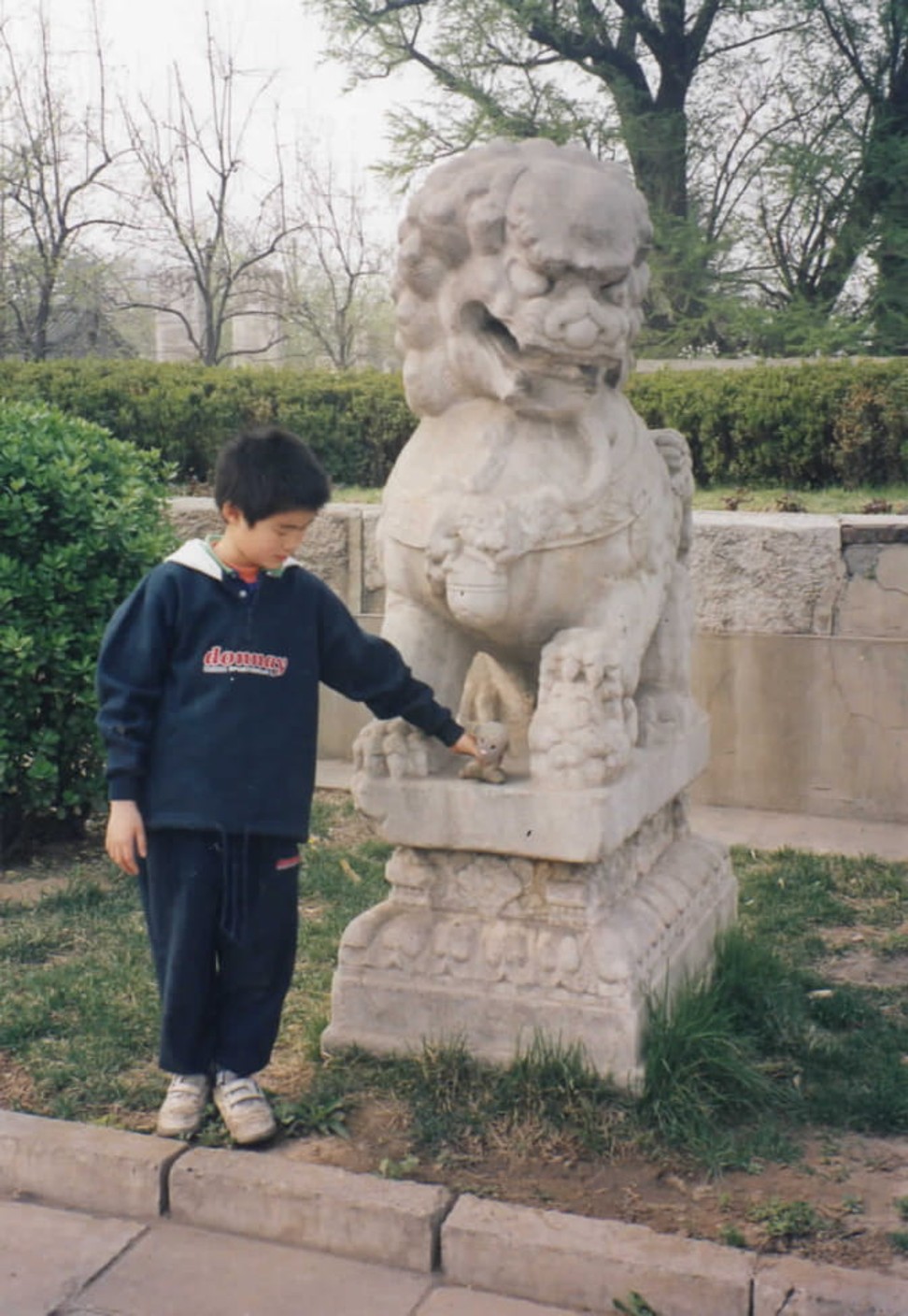

Born and raised in Cambridge, in eastern England, Cheng is the son of parents who emigrated from Beijing in the 1980s. His mother, Xin, is a freelance Mandarin interpreter for the British police, mainly on call to help with immigration cases, while his father, Jen, whose own parents were from Hong Kong, designs “some kind of internet bank security software” in China, to where he returned when Ken was 11 (“I know a few British-Chinese people who have their parents in two places, but they’re still together, so yeah, it’s an interesting arrangement”).

Chatting in the basement of a central London bar, Cheng, dressed all in black, cuts a slightly apprehensive figure at times. He sits with his legs contorted and shuffles nervously as our conversation is punctuated by the sound of the sole of his trainer repeatedly squeaking against the table leg.

It turns out that Cheng has not discussed his comedy in detail with either of his parents and, when I ask what they make of his shows, he says, “I don’t let my parents come to my gigs. No! I just am very weird about that. I just can’t have them see me in that light.” Don’t they ask about it? “Yeah, they do! I think I keep too many secrets.”

The situation is even more strange when you discover that the show he is taking to Edinburgh (the world’s largest arts festival) this summer, Best Dad Ever, is based on his parents.

If Cheng struggles to hold even a cursory conversation with them about his material, getting their consent to place them at the heart of his tour sounds like a tricky proposition. Nonetheless, Cheng insists that nothing is off-limits.

“This is going to be a very personal show,” he says. “Anything that’s funny or interesting will go in. It’s very much about the most interesting or the most honest perspective.”

Cheng admits there are stories about his dad in it “which I don’t think would go down very well”. But, he says, he is less concerned about betraying familial confidences than “them seeing me talk about things that you don’t really want your parents to see you talk about”.

It is at this point that I ask about his most-watched YouTube clip, the hilariously toe-curling “Mark Liu’s J**k Off Instruction Video – For Women”. Liu, a character Cheng has since abandoned, is a socially awkward student who resorts to online videos to stamp his mark on campus. To make matters worse, Cheng has added a (clearly tongue-in-cheek) comment to the four-year-old clip that reads: “PS big shoutout to my Mum for helping me film this video.”

Have his parents seen their son spend seven minutes instructing women how to masturbate? “That’s unclear actually,” he says, haltingly. “Because they might have … I mean, oh. I, I really don’t – see that’s, that’s one thing where I, like … that’s exactly it. You’ve pinpointed the exact thing of, oh, I can’t. I don’t want to fathom that.”

Would they mention it if they had? “No. No, I hope not. I would not want to have that conversation.”

Do they use YouTube? “Yeah. Yeah, yeah, it’s very likely if – yeah, it’s on my channel,” he says, sounding utterly defeated.

Virtually all of Cheng’s childhood friends were white and he assimilated quickly and comprehensively. A kid obsessed with Star Wars, he gave up learning Mandarin soon after starting school. “I just decided I needed to speak English and I spoke only English at home as well.”

In his new show, he talks of the 100 toy lambs that formed the backbone of his childhood between the ages of four and 12. “I was obsessed with them. I kept writing sci-fi stories about them. I wasn’t very social, but I did have all these weird hobbies. So that’s a big part of the show – how I didn’t develop very normally as a kid.”

Toy pets aside, Cheng was aware from early on that he would never entirely fit in. “I guess as a kid you also think you’re different because you’re you,” he says, “so it’s very hard to divorce the two.” Cheng recalls the school bullies who would “use racial slurs or say, ‘Jackie Chan!’ and stuff like that. Personal insults have always offended me, not just racial ones. But there are times when you’re like, all right, someone’s reminded me I’m different.”

Thoughts of professional comedy would not come until much later, but, Cheng adds, “I remember always playing up that I could mention I’m Chinese and that would be funny to people. I would say something as basic as, ‘Hi, I’m Ken. I’m Chinese,’ and people would just find that funny.”

One of Cheng’s most popular set pieces revolves around him deconstructing his most hated English proverbs. On “To kill two birds with one stone”: “If you’re going around killing birds with stones, you have issues. If you’re going around killing birds so often that you need a time-saving way of doing it, that is an obsession.”

Cheng plans to turn his focus to Chinese phrases next “because I’m kind of bored with all the English ones”. “I like the proverb ‘Don’t add legs to a snake’. It’s essentially saying that more is not necessarily better.” He also cites: “One drop of semen is worth 10 drops of blood,” which, according to The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Chinese Language, is a warning of the dangers of Mark Liu’s specialist subject.

Cheng is also active on Twitter. His “Thread where I disrespect every flag of every country one by one” went viral. He said of China’s flag that its “subliminal message to give it 5 stars earns it 0 STARS”, while Vietnam received the verdict: “If I wanted to see this crap, I would’ve just zoomed in on the Chinese flag.”

Hong Kong didn’t make the cut but, when I ask what he makes of the Bauhinia, he comes over all coy. After getting up an image on his phone, he declares: “It’s all right, actually. I think it’s kind of cool. There’s a natural beauty about it.”

But I thought you were meant to slag it off, I protest.

“If I just do Hong Kong in this interview, it will look like I’m really going after Hong Kong,” he says.

Cheng has been less circumspect in the past. In a tweet responding to a BBC article asking if a Gap advert featuring only white children was racist, the comedian proclaimed, “This racist exclusion from adverts must stop. You can’t omit Chinese kids just because they are all ugly as f**k.”

“You’ll remind me of tweets that I definitely post but just forget,” he says, explaining that he had already deleted all online communication before 2014 “because I just think, ‘Why risk it?’ I can’t believe politicians are still not doing that.

“Right now, all my stuff is offending racists and I’m not bothered.” His tweet “Terrorism is one of the only areas where white people do most of the work and get none of the credit” has been liked 200,000 times. “But you do run the risk of going too far,” he warns, pointing to comedians who have shown how online outbursts “can boil up into a critical mass of hate”.

Cheng had given no thought to a career in comedy when he began his mathematics degree at Cambridge University. Nor was it where he turned when he dropped out after a year.

It’s a weird one because there’s a point in poker where you can’t assign that to real things or you’d spend all your time going, ‘Oh, I lost a car, I lost a house’. You have to dissociate yourself from it a bit

Not only was he struggling to keep up with the course, his studies were getting in the way of his poker. He had started playing online at school, making a few thousand US dollars here and there. His decision to abandon his degree was the source of several arguments with his disappointed mother, but, he says, he did not feel a sense of failure.

“I was quite … what’s the word, I was quite triumphant that I actually made a decision about my own life. I was going, ‘I’m making my own path now.’ I’d never done that before.”

Gambling would provide Cheng’s sole source of income for more than a decade; he gave it up only this year, to focus on joke-writing.

He smiles hesitantly when I ask what kind of figures we are talking about. “I hate answering that question because there was one point where I had much more money than I have now.”

He eventually admits that he could make – and lose – more than US$100,000 in a day. “It’s a weird one because there’s a point in poker where you can’t assign that to real things or you’d spend all your time going, ‘Oh, I lost a car, I lost a house’. You have to dissociate yourself from it a bit.

“Obviously, now, when there is more pressure on my finances, what with London rent and me taking a lot of time off to do comedy, which for a while wasn’t making me anything but was just an investment for the future, there’s certainly more pressure.”

Furthermore, the adrenaline rush from a successful gig simply cannot compare to a bumper poker win.

“There’s no bigger high than winning US$100,000. You’ve stayed up to 8am and you can’t sleep, the high is so much. And obviously that feeling of financial security is unrivalled. If you win US$100,000 you feel, ‘I will probably never have money problems in my life.’”

Mercifully, the troughs do not match up either.

“There’s no bigger low than losing money,” Cheng says. “Even a tiny bit of money. Comedy has lows but you can think, ‘Fifty people saw me not be funny for 10 minutes. What’s the damage?’ I felt embarrassed for 10 minutes. But really my life has not been negatively affected.”

Without the financial cushion afforded by his winnings, Cheng may never have risked his career change. The confidence and emotional development he gained were also crucial.

“It taught me to go out of my comfort zone, for one. I would have never gone, ‘I’m just going to sign up for that gig.’ It’s very much a poker mindset to be like, ‘OK, I’m going to make a thing happen because, why not?’

“There’s a big emotional element to poker, a huge one. It helped me handle risk and handle loss. You have to be very rational about everything that happens in poker – and the same in comedy. When you have that rationalisation, you’re like, ‘So what if nobody laughs at me.’

“I recommend everyone try and get good at poker – it makes them better at life in general. Poker taught me more than any of my first 15 years of education, including a year at Cambridge. Poker taught me how to learn.”

The icing on the cake – if any were needed – is that in Britain, poker winnings come tax-free.

“We are probably the only gambling tax haven in the Western world. I never did tax returns. I have to do one this year because of comedy and I don’t actually know how.”

Cheng’s extraordinary biography does not end there. Remarkably, he discovered the extent of his own cultural heritage only at Christmas, while chatting with his mother.

Hsiung, Cheng’s mother’s grandfather, was, according to his biographer, Dr Diana Yeh, “a completely unknown student who within weeks literally shot to worldwide fame”.

Hsiung had made a name for himself in China as an adept translator of English film subtitles and plays by the likes of George Bernard Shaw (Pygmalion) and J.M. Barrie (Peter Pan) into Chinese. The first play of his own that he pitched to the Brits, after travelling to London in the early 1930s, was not received well. What would now be known as a “kitchen sink drama”, it portrayed the political realities and class divides of contemporary China. “The British weren’t interested in that; they were interested in the exotic never-never land of a China of the ancient past,” explains Yeh, a lecturer at City, University of London, and author of The Happy Hsiungs: Performing China and the Struggle for Modernity (2014).

Every once in a while, there’s a sudden China fever; where everyone suddenly wants to do stuff about China – and, obviously, we’re kind of going through one now.

It was Hsiung’s second script that captured the public imagination. Lady Precious Stream was a modern reworking of the ancient Peking opera Wang Baochuan. “Keeping a touch of the exotic but making it palatable to British audiences” was what helped the production become the first by a Chinese writer and director to be staged in the West End, and then on Broadway, Yeh says.

“This is a phenomenal story because there was no Chinese writer having such an impact,” she adds. “There was no other Chinese writer who was known at all. He and the play became household names. He and his wife, Dymia, were interviewed by publications like Good Housekeeping.”

Queen Mary went to see it in London, along with vast swathes of the diplomatic corps, keen to educate themselves on Chinese customs, while American first lady Eleanor Roosevelt got a ticket for a Broadway performance.

“It received huge critical acclaim but was also very, very politically important,” Yeh says, “and it was also astonishingly popular.”

She adds that “every once in a while, there’s a sudden China fever; where everyone suddenly wants to do stuff about China – and, obviously, we’re kind of going through one now.”

Cheng is perhaps a beneficiary of the latest wave of Sinophilia. He is at the vanguard of a small but mighty group of Asian comedians cracking Britain’s comedy circuit. Others are Phil Wang, Rick Kiesewetter, Yuriko Kotani and Nigel Ng.

Indeed, it was seeing Chinese-British comedian Wang on stage that put ideas into Cheng’s head.

“The first live gig I saw, Phil Wang was on the bill and that definitely, subconsciously affected me, being like, ‘Well, that’s someone like me up there who can do it,’” says Cheng. “Seeing that definitely makes you think, ‘Well, why don’t I give it a go?’”

On why now seems to be a particular moment for British-born Asian comedians, Wang says, “I think the no-nonsense aspect of the Chinese personality lends itself well to comedy. It provides a funny means by which to dissect the ridiculous aspects of life and society.”

We have a problem with diversity in this country. As in America, there are issues with those who are construed as foreign, as not being part of the British nation’s history

It will be fascinating to see if Cheng goes one further than his forebears. His great-grandparents “did find it difficult to break out of being that exotic ‘other’”, Yeh says, “so they were never fully accepted as modern subjects. They were always seen as, ‘Ooh, the Chinese person’. Rather than a writer, it would be ‘a Chinese writer’.

“We have a problem with diversity in this country. As in America, there are issues with those who are construed as foreign, as not being part of the British nation’s history.”

Cheng is clearly already on the path to becoming much more than “Ken Cheng: Chinese Comedian”.

“Ken is pure logic distilled into a very funny man with a disarming deadpan delivery,” says Wang. “I think his future is very bright.”

Perhaps the mathematician-turned-poker star will go all in to make the leap his great-grandfather never managed. I for one won’t be betting against it.

Ken Cheng’s new show, Best Dad Ever, will run at the Bedlam Theatre as part of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in August.