Sinologist Jeffrey Wasserstrom shares his experience of last year’s Hong Kong protests, their anger and utopia, and why he is unlikely to visit China again

All in all, it has been a very Jeffrey Wasserstrom kind of year. Hardly a week has gone by in which global headlines have not seemed like an extension of his own interests as a historian, scholar and one of the West’s leading sinologists. Wasserstrom’s profile page at the University of California, Irvine (where he is Chancellor’s Professor of History) lists those interests as “China, Protest, Globalization, Gender, Urban”. Very 2020.

“Perhaps the furthest back in time we can go to find a noteworthy underestimation and memorably mistaken prediction about Hong Kong is to a letter dated April 21, 1841,” he writes, referring to Lord Palmerston’s disappointed description of Hong Kong as a “barren island with hardly a House upon it”.

As if to prove the point, only a few months after Vigil’s up-to-the-second reportage, its portrait of Hong Kong as a city of protest already seems a thing of the past.

I receive my own lesson in 2020 chaos theory from my two conversations with Wasserstrom himself. The first comes the day after Donald Trump and Joe Biden went head-to-head in their opening US presidential debate. “I have gone to lots of places and the attitude towards America has always been mixed, you know? Admiration, envy, annoyance. But pity? With Covid and Trump we are just pitiful. That’s a new thing to adjust to,” he says.

Fast forward a week and Trump the bumbling orator is now Trump the Covid-19 patient, a self-appointed coronavirus guinea pig and miraculously recovered leader ordering the country to get back to work. “At least one of Trump’s high-profile supporters was saying this is a Mussolini moment for the president, meaning it in a positive sense,” says Wasserstrom. “His critics are saying the same thing about Mussolini, only in a negative sense.”

It can be mildly daunting to keep up as Wasserstrom shifts gears: contemporary Hong Kong to mid-20th century Shanghai to the Luddites in 19th century England to Bratislava during the Prague Spring to Poland’s Solidarity movement of the 1980s. And yet, it is a testament to his clarity and eloquence that I feel considerably better informed at the end of our talks than I did at the start.

Another notable aspect of Wasserstrom’s career is his deft ability to write for academic readers and general audiences alike, whether in a tweet, an op-ed for The New York Times or a podcast.

I suspect this productivity means Jeffrey Wasserstrom loves what he does: talk, debate, exchange ideas and teach. And yet, he tells me, these forums are in short supply at the moment, at least in what might be called the “old normal” of face-to-face water cooler chat at UC Irvine. Wasserstrom has just begun an academic year unlike any other: because of coronavirus, he is mainly teaching remotely.

“They are setting up things like outdoor study halls under tents,” he says. “It was very weird. The last time I saw anything like it was in the umbrella movement with those study areas for students.”

Joining social movements is a valuable part of education

Wasserstrom is adapting to Zoom seminars, but is quick to add that online classes raise significant questions, not least for his interactions with students from mainland China and now Hong Kong.

“There has been discussion among China specialists about how we teach. I won’t have a discussion session about Chinese history that has people from different parts of the world who might be recording each other. Under the national security law, all kinds of things would be potentially sensitive,” he says. As a result, Wasserstrom is supplementing these meetings with one-to-one Skype tutorials. “It is more time-consuming but the only way I can think of to have interaction that isn’t dangerous.”

Kung Fu was more or less the sum total of Wasserstrom’s knowledge of China before university. Born in 1961, he grew up in Santa Monica, not far from his current workplace. His family was progressive. “We went to anti-Vietnam war marches. I was interested in politics in that sense. I was 11 when Nixon went to China. But I don’t have a strong memory of it.”

What he does remember is the moment in 1978, not long after arriving at UC Santa Cruz, when he saw a poster announcing a student friendship delegation to China. Wasserstrom instantly signed up for Chinese language classes, a rarity at American universities at the time. “Then I realised that nobody going to China the following year was taking Chinese, which I thought was odd,” he says, explaining why he dropped out of the delegation.

He continued with the Chinese class, however, already fascinated by the “structure of the language” and inspired by the life-changing reading list. This included works by Jonathan Spence, Frederic Wakeman’s 1966 book Strangers at the Gate (Wasserstrom would later study with Wakeman during his doctorate at UC Berkeley), and that classic literary gateway into China, a Judge Dee mystery.

Wasserstrom gained interest in “revolutions, upheavals and protests”, in European settings such as England’s Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution. He wondered what would happen if the questions historians such as E.P. Thompson were asking of 19th century England were applied to a country like China. “To what extent is there something general called a ‘revolution’? And to what extent are the revolutions in different countries distinctive?”

Wasserstrom’s resolution to concentrate academically on China was also determined by real-world practicalities. He judged that if his ambitions to become a historian in the competitive university sector did not work out then his knowledge of Chinese could have value in other arenas. His foresight was justified, ironically, when he won his first teaching job at the University of Kentucky. The college wanted an East Asian historian (preferably with expertise in Japan) in part to negotiate with a nearby Toyota plant to raise funds for the programme.

“What’s funny now is this seems wonderfully pragmatic. It was kind of pragmatic. But at that time in America, if you wanted to be really pragmatic you would study Japanese, because Japan was the economic powerhouse. Other people said you should study Russian, because Russia is the geopolitical rival to America. My wife said in the 1990s that I had the last laugh because China was already on its way to becoming what it now is – both Japan and Russia in the American context. It is the economic and the geopolitical rival,” he says.

There was a clear sense that the Mao era had been put behind them, and China was moving in a new directionJeffrey Wasserstrom

Many of the grand themes that have dominated Wasserstrom’s career can be traced to his first visit to China, in 1986. He chose Shanghai as an attractive destination and a research project: a “cosmopolitan city” created in part as a “simulacrum of a Victorian city. Huangpu park with its gazebo, or the buildings along the Bund in the British style”.

The architectural parallels inspired other comparisons: between early English protesters like the machine-smashing Luddites and Shanghai rickshaw pullers, who perpetrated similar violence on their carts. It did not take Wasserstrom long to realise that protest had not been consigned to the city’s past but was stirring on university campuses in the present. “It wasn’t so much political as [the result] of uncertainty about where China was heading. There was a clear sense that the Mao era had been put behind them, and China was moving in a new direction.”

Wasserstrom remembers reading posters on campus and attending the protests. “It made my advisers a little bit nervous for the week they were ongoing. They would say to me, ‘You study youth movements and protests, but these are very different, aren’t they?’ I would agree and then spend time noting how similar they were.”

Where Shanghai’s students did seem different, he says, was in comparison to those in the US. “In America, young people and students are told they shouldn’t have a role in politics. There isn’t a natural link between student activism and worker activism. China was very different, with its long tradition of the scholar as the conscience of the nation and the celebration of the youth movements that helped bring the Chinese Communist Party to power.”

Wasserstrom was himself a postgraduate student in the US when the Tiananmen protests began about two years later. He did not travel to China to witness them, largely for personal reasons: the birth of his first child in April, a dissertation to finish and that first job to secure. But the decision to stay put was also based on the lessons of 1986.

“As the protests began in 1989, initially the most surprising thing was that they continued. After about a week, People’s Daily called them new Red Guardism and told students to get off the streets. Even if you wanted to witness it, you felt that at any moment it would stop. But the longer they lasted, the feeling grew that against all odds this is actually going to be a time when things change. Then it was a surprise that there was the repression.”

Indeed, Shanghai and Hong Kong are intimately connected in his mind and writing: he compares them frequently in Vigil, and throughout our conversation. “I went through a period of thinking Shanghai isn’t a political place the way it used to be,” he says, referring to his visit in 1986. “And then there were protests. Hong Kong was where I would go to get away from protests. Then it became the place I went to observe protests. It snuck up on me how attached to Hong Kong I had got. The fact that Hong Kong was the one city left that was both part of China and also a very different kind of space. That’s what’s collapsing and what so many people are grieving for right now.”

What the two cities share for Wasserstrom now is similarly anomalous identities. He cites Shanghai’s intriguing combination of Chinese and European influences, alongside its brief occupation by Japan. Hong Kong seemed a more straightforward case, he argues, until its “odd transition” from a colonial city to semi-independence to its current absorption into another country. “In some ways now it’s becoming more straightforward to think about as a second period of colonisation, which is how some activists were talking about it all along. But the protest movement does seem more like a second anti-colonial movement.”

What Tiananmen showed was the tremendous risks and the impossibility of standing up to that sort of regime. The modelling of bravery can be inspiring even in a failed senseJeffrey Wasserstrom

I boil down a multitude of questions swirling around my head to just two. What has Hong Kong taught Wasserstrom about why people protest, and what keeps them protesting?

“It is very important that sometimes the impossible succeeds, and there are myths in people’s mind. The David and Goliath story of triumph over impossible odds.” Gandhi is another example. “Remember for decades you could ask, ‘Are the things Gandhi is struggling for ever going to transpire?’ The answer would be no. Britain was the most powerful empire in the world. What chance does any kind of movement stand?”

What it seems Wasserstrom finds even more stimulating is how failed protests can exert positive if unpredictable influence. “I have met people who were involved in the Eastern European protests of 1989 who, when they find out I study China, say that they were very inspired by Tiananmen. At a rational level, what Tiananmen showed was the tremendous risks and the impossibility of standing up to that sort of regime. The modelling of bravery can be inspiring even in a failed sense.”

The challenge for so many protest movements is maintaining momentum while fighting exhaustion and boredom. “I am interested in what keeps people continuing to struggle,” says Wasserstrom. Myths and iconographies have something to do with it, he suggests, citing the importance of the umbrella as a rallying symbol, or the invaluable footage of “Tank Man” at Tiananmen. Wasserstrom tells me how a similar portrait of futile defiance – Ladislav Bielik’s photograph of a man baring his chest before a Soviet tank in Bratislava during the Prague Spring of 1968 – helped set the tone for Solidarity’s Adam Michnik, who rejected a government deal that would have enabled him to leave prison on the condition he left Poland.

Wasserstrom wonders aloud whether the apparent defeat of the Hong Kong protests might still produce similar resolve. “What gets people onto the streets and keeps people on the streets? One is disgust, anger and wanting to defend the right to protest. Another is the utopian feeling of community and solidarity when you are there. It’s not rational. Cantonese is full of this familial imagery for what happens on the street. You are part of one community that exists. I certainly felt during [the umbrella movement] that was one of the most utopian settings I have ever been in.”

Hong Kong protests will inspire world even if they fail, historian says

Listening to Wasserstrom speak with such warmth and respect, I realise that Vigil is not just an elegy for a historical incarnation of Hong Kong, but for Wasserstrom’s own relationship with the place and its people.

“It was an amazing experiment. It is amazing that Hong Kong stayed as free as it did for as long as it did. It is still extraordinary that the South China Morning Post has more variety of news in its pages than any newspaper since 1949 has had in any part of the People’s Republic of China.”

Over the past few years, he had slowly reconciled himself to the possibility that he might have visited mainland China for the last time. “I have worked on Tiananmen since the beginning of my career. When I am in the United States, I do not worry about what I say about China or write about China. If they banned me, then they banned me. It was the price of doing business. I always thought how much harder it must be if you worked on Xinjiang or Tibet.”

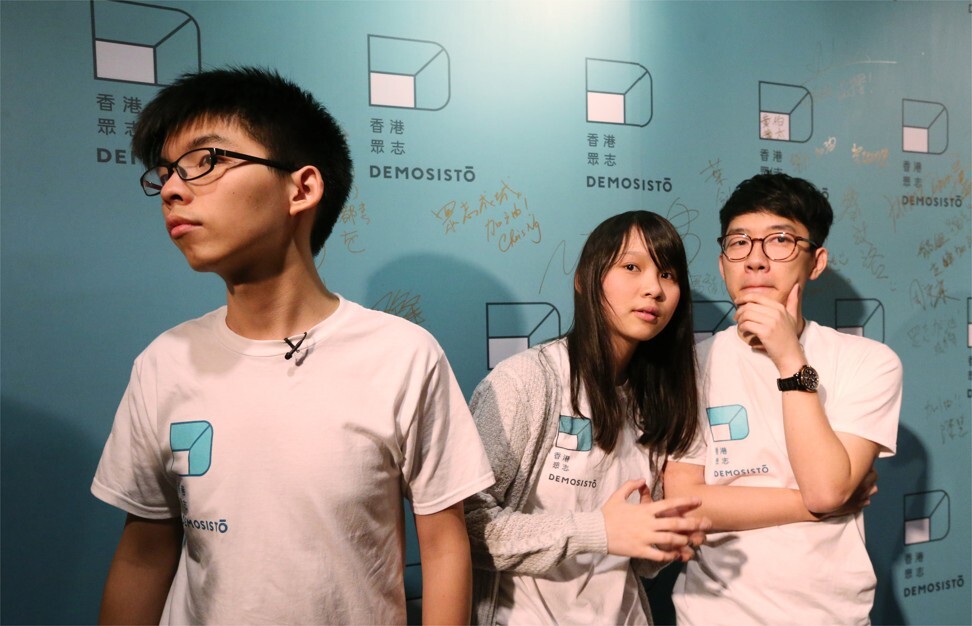

At the same time, he believed, “I will always have Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, I behaved exactly as I did in the West. I didn’t think twice who I met with.” But with the national security law, this has changed. “In some ways, I’d have more trouble going to Hong Kong than the mainland, because I have known Joshua Wong and Nathan Law and Agnes Chow. I can’t work out how I would go there safely.”

His regret is tempered by awareness that his focus was shifting towards more global topics. The conversations that began while researching Vigil will continue in the Hong Kong diaspora. “When I go to London I won’t think twice about meeting up with Nathan Law.”

How ready the world is to make those changes is yet to be seen. “There is a limited amount of global outrage about [Hong Kong]. There is a limited call even for a boycott of the Winter Olympics. Clearly the Communist Party wants the Games to happen, wants world leaders to come. And world leaders probably will come. If they don’t it will be because of the combination of Xinjiang and Hong Kong.”

Wasserstrom offers one final comparison. “The last Hong Kong protest I saw, and perhaps will ever see, was in December 2019. It was a vigil-like gathering some high school students had organised commemorating people who had been injured or died in earlier events.” Wasserstrom compares this solemn memorial to one held in 1989 in honour of Jan Palach, the Czech protester who two decades earlier committed suicide by self-immolation to protest the Soviet crushing of the Prague Spring. “I don’t want to romanticise martyrdom, but the 20th anniversary of Palach’s death was one of the events that began the road towards the Velvet Revolution.” A second or two later, he adds: “Success and failure are very curious things.”