- With much of the world in turmoil, this list of new and old books will open your eyes to change in its many forms, whether via magic, mayhem or a monkey king

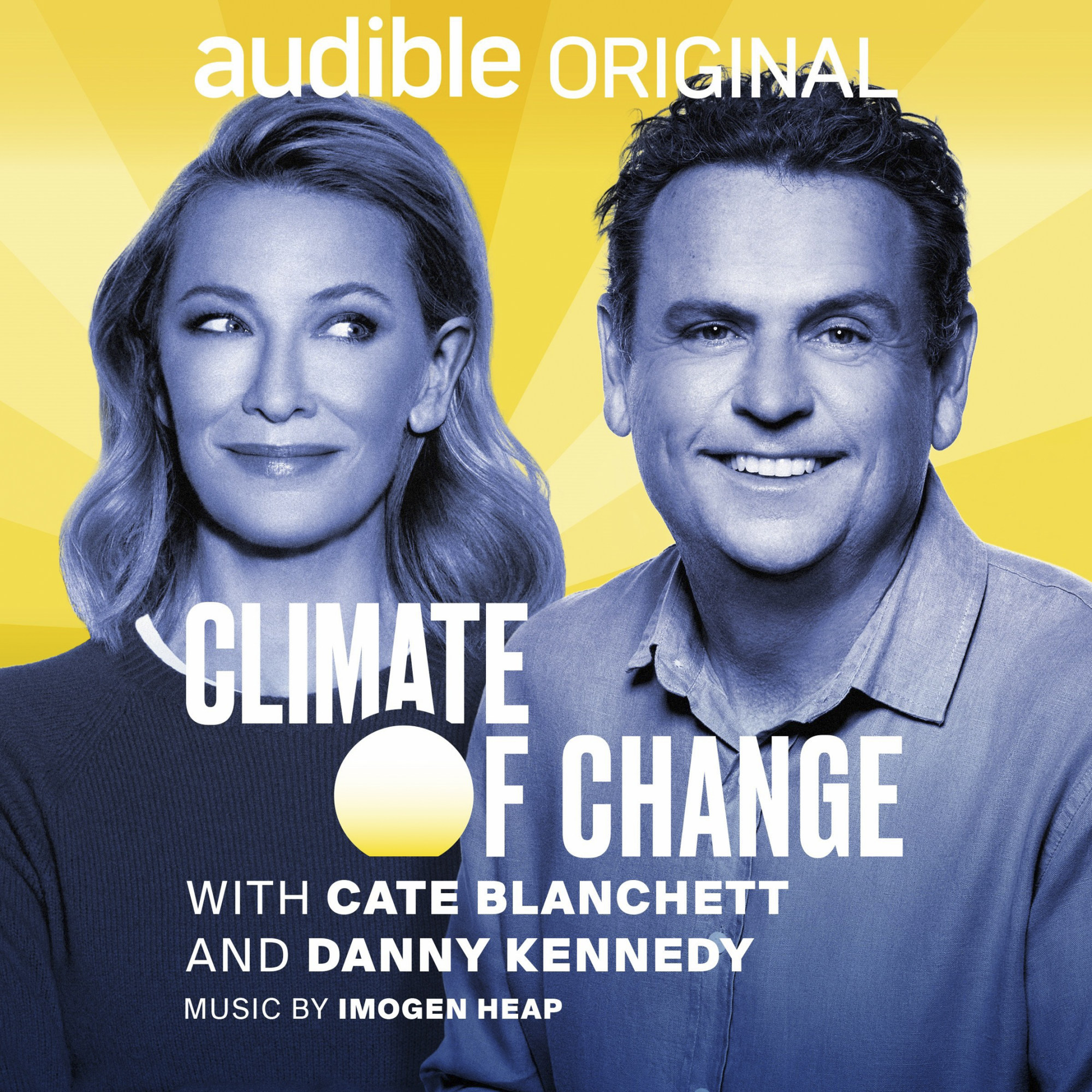

A few weeks ago, I found myself listening to Climate of Change, a new podcast in which Oscar-winning actress Cate Blanchett casts an eye over the latest in green energy innovation with help from “dear old friend” and clean-technology entrepreneur Danny Kennedy.

The series promised stories that “will, hopefully, give you hope”.

It began, however, with Blanchett’s familiar velvety voice confessing her almost daily fear of “being swept away on this tide of bad news”. Blanchett named a few contenders – human-rights abuses, refugees fleeing war zones, failed leaderships, climate change – before confessing, “I have absolutely no idea what to do about this mess we’re in.”

What made Blanchett’s apocalyptic list feel even more apocalyptic were all the bad news stories she left out: Covid-19 and its fallout; ongoing travel chaos; Ukraine; possible Cold War, part two; escalating tension everywhere from the Greek islands to the United States, which according to headlines is on the brink of civil war (again).

Casanova: world’s greatest lover or debauched sexual predator?

Given all this instability, the question of what to read during the summer holidays may be the best opportunity to take a few minutes out, breathe and, with this list of books – from old to new and in between – consider these various beams of our spectral theme as a kind of coping mechanism, rather than stewing away at the myriad possibilities of our impending peril.

1. The Metamorphoses, by Ovid (translated by Stephanie McCarter. Penguin Classics, 2022)

It’s hard to think about the word “change” without thinking about Ovid’s The Metamorphoses, the mythic account of gods, mortals and everything in between that was written in ancient Rome more than 2,000 years ago.

Change, a little ironically, is the main theme uniting the poem’s many episodes. The Metamorphoses is the first place to look for the definitive versions of Echo and Narcissus (transformed into sound and flower respectively), Pygmalion (statue to flesh), Philomela (nightingale) and Midas (everything to gold).

As well as inspiring many of the world’s greatest writers (Dante, Shakespeare, Boccaccio, Kafka), it has challenged many of the world’s best translators. The latest is Stephanie McCarter, a professor at The University of the South, in the US state of Tennessee, whose new translation for Penguin Classics will be released this autumn.

Speaking in 2019, McCarter said, “One thing that is particularly true of Ovid is that he changes as we change.” What this meant for McCarter herself was a complete overhaul of the English-language depictions of the sexual violence in Ovid’s Latin original.

There are, McCarter points out, 50 rapes in the poem, many of which have been obscured (or even excused) by previous translations. David Raeburn’s Penguin edition of 2004 rendered the rape of Leucothoe by sun god Helios as: “Protest was vain and the Sun was allowed to possess her.”

The violence of the assault is diluted by the passive voice and the whitewashing of Ovid’s word vis, meaning “force”. What makes this prettifying smokescreen ironically apt is the unsettling way Ovid fuses beauty and brutality in so many of his transformations. Leucothoe is turned into frankincense after she is raped, while Philomela becomes a nightingale.

What are ‘sponge cities’? How China is leading fight against urban flooding

For McCarter, these metamorphoses tantalise as metaphors of trauma, symbols of female vulnerability and a critique of the way society averts its gaze from the violence lurking before its very eyes.

2. Four Thousand Weeks, by Oliver Burkeman (Bodley Head, 2021)

Journalist Oliver Burkeman has made a career out of providing “life-changing advice”, as he wrote in his final column doing just that for The Guardian newspaper. Much of the wisdom Burkeman accrued over those 14 years has been condensed into Four Thousand Weeks.

Burkeman begins with a fundamental, if startling observation: “The average human lifespan is absurdly, terrifyingly, insultingly short. Assuming you live until eighty, you’ll have had about 4000 weeks.” Time management isn’t just important, Burkeman concludes, “Arguably, time management is all life is.” Yikes.

A major problem posed by books like Four Thousand Weeks is that some of us spend far more of our precious time reading about living life to the full rather than doing it. Burkeman is a refreshing exception.

Even if you don’t follow his advice on avoiding busyness, distraction or tedium, his prose is so enjoyable you won’t feel time spent in his company is time wasted. He can be erudite, quoting German philosopher Martin Heidegger on how to lead a more authentic life. He can be funny, contrasting his own adventures in parenting with the idealised manuals he bought as preparation for fatherhood.

Like all the best self-help guides, Burkeman’s doesn’t tell us anything we don’t know already; rather he reminds us about truths we are probably too tired, preoccupied or panicked to notice.

3. I Ching, Book of Changes (translated by John Minford. Penguin Classics, 2016)

Of the many anxieties outlined by Oliver Burkeman in Four Thousand Weeks, perhaps the most recognisably 21st century is the difficulty of living in the now. How many of us wish away the present in the hope of reaching “some calmer, better, more fulfilling point in the future, which never actually arrives”? Then again, when haven’t humans tried to see into a calmer, better future long before it arrives?

Perhaps the most famous, and certainly influential, example is the I Ching, the great Confucian text that emerged out of Shang dynasty divination rituals that used “oracle bones” to predict everything from toothaches to foreign policy.

Whether the bones prophesied the Shang’s own overthrow by their Zhou neighbours is open to debate. Perhaps that explains why the Zhou replaced throwing bones with casting dried stalks from the yarrow plant, before interpreting the patterns using the 64 diagrams that would form the I Ching.

The first part of the text is often called the Zhouyi, literally “The Change of Zhou”. Just what this “change” (yi) meant has been widely debated. John Minford, in his Penguin edition of the I Ching, suggests changes in the weather. Others have proposed ancient folklore involving the sun and moon.

For scholar Joseph Adler, the answer is a characteristically Chinese notion “that change and transformation are fundamental to the nature of things”.

Change is the explicit subject of Hexagram 49 (XLIX, geming), which includes that aforementioned change of dynasties: “King Wu overthrew Shang. This Change of Mandate Followed Heaven’s Flow.” Which is easy for the Zhou to say.

‘Human connection specialist’ Simone Heng on reconnecting with her mother

Most of the changes draw on nature or the spiritual realm: “Heaven and Earth Change, The Four Seasons Come to pass”; “With Change, Comes belief”; “Change is Apt, Regret goes away”. According to Minford’s commentaries, change as advocated by the I Ching is a process of natural renewal, an act of self-cultivation and possibly even a revolution (geming gives us the modern Chinese word for revolution).

Nevertheless, change should never be rushed: “Radical Change is sometimes necessary in an organisation. But it needs to be handled with care and a sense of order and timing […], or it may be resisted fiercely.” Perhaps there’s something in this prophecy business after all.

4. China Hand, by Scott Spacek (Post Hill Press, 2022)

Summer is traditionally the time for exciting beach reads and thrilling airport blockbusters, which makes China Hand especially welcome. An impressive and enjoyable thriller by first-time novelist Scott Spacek, it is set during a period of bewildering transformation in pre-millennial Beijing, which like China itself was straining to harness its Communist past to a global capitalist future.

Enter Andrew Callahan, a youngish American whose university major in modern Chinese government wins him a job teaching future diplomats, military officers and spies at the International Affairs University. Many of Callahan’s students view him as another sign of progress. A few are less amiable.

He enters one classroom to a muttered insult: “Americans look down on Chinese.” Later, he is informed: “China welcomes its friends with fine wine […] but greets its enemies with shotguns.”

Callahan certainly takes his share of beatings – first in a barroom brawl, later in a boxing ring. These are only precursors to the simmering tension that follows the US bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, which killed three journalists. American claims of a mistake spark protests demanding “blood for blood”.

In this life-or-death atmosphere, the CIA approaches Callahan to become an undercover agent. His mission is to help the top-level General Jiang defect to the US before a rumoured coup triggers a change of power. If this isn’t nail-biting enough, Callahan just happens to have fallen for Jiang’s daughter, Lily.

Scott Spacek (a pseudonym) is a tech adviser who has lived in China for two decades, and claims that much of China Hand is inspired by real events. True or not, it will make any summer lull speed by a little quicker.

5. Alice in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll (illustrated by Chris Riddell. MacMillan Children’s Books, 2020)

Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, like Ovid’s Metamorphoses, is a literary classic propelled by change. Carroll’s famously elastic if mercurial heroine experiences so many shifts in place, mind and body that she struggles to answer that most basic question, “Who are you?”, as posed by the hookah-smoking Caterpillar. “I – – I hardly know, sir,” Alice replies. “At least I know who I was when I got up this morning, but I think I must have changed several times since then.”

When the Caterpillar asks what this means, Alice grows even more confused: “I can’t explain myself,” she replies with a typically Carrollean play on words meaning that Alice herself is unable to explain, and also that Alice can’t explain Alice: “because I’m not myself, you see,” she concludes.

The Caterpillar doesn’t see, but Alice’s millions of readers probably can. For as fantastical as Alice’s sudden changes undoubtedly are, they are not so very different from the ones most human beings experience at some time or another.

Alice in Wonderland has proved every bit as supple as the story it tells. If Alice became famous because of John Tenniel’s illustrations, she has kept adapting – whether through Disney or Jonathan Miller or Johnny Depp’s abysmal Mad Hatter.

Proof is provided by a new edition illustrated by revered children’s author and illustrator Chris Riddell. He simultaneously honours Tenniel’s seminal imagery (see, or don’t see, his Cheshire Cat and White Rabbit) and shakes it up: his Alice startles with a no-nonsense short black bob, while his Mad Hatter is a (pleasingly un-Depp-like) woman.

6. The Power of Crisis, by Ian Bremmer (Simon & Schuster, 2022)

It is easy right now to read change as a euphemism for crisis. This in a nutshell is the thesis of The Power of Crisis, an unflinching, but curiously hopeful new book by Ian Bremmer, an academic at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, in New York, and founder of global research consultants the Eurasia group.

Bremmer divides our global crises into four chapters, which doesn’t make them feel any smaller. The first examines two potentially world-changing disasters: America’s potential conflict with China, and America’s potential conflict with itself.

Of the first, Bremmer writes, “Many in Washington and across the country see China’s rise […] as an ill omen of American decline and a threat to its future.” Meanwhile, “Many in Beijing and across China see US resistance to China’s progress as a clumsy attempt to protect Western privileges by stunting China’s growth.”

Bremmer explains America’s potential civil war, which is raging ever more fiercely after recent changes to gun, abortion and police legislation, as the result of partisan politics, widening wealth gaps and institutional racism. If you already feel exhausted, buckle up: Bremmer goes on to unravel Covid-19, climate change and how emerging technologies are already transforming life as we know it.

The good news, Bremmer argues, is the world has always needed a crisis to refresh values such as cooperation, mutually beneficial innovation and basic human decency: just look at the speed with which the Covid-19 vaccine was produced. Here’s hoping he is right once more.

7. Monkey King, by Wu Cheng’en (translated by Julia Lovell. Penguin Classic, 2021)

Wu Cheng’en’s Journey to the West is our third literary masterpiece propelled by transformations, transgressions and transcendence. Like Metamorphoses and Alice in Wonderland, each fabulous episode melts so easily into the next that you may feel like you’re having the best dream ever rather than reading a classic of the Ming dynasty.

Journey to the West has proved every bit as adaptable as Alice in Wonderland and the Metamorphoses. British historian Julia Lovell is the book’s latest translator.

She begins by explaining why her abridged edition is about a quarter the length of the four-volume original. This, combined with a desire to connect 16th century China with 21st century English-speakers, signals an intention to attract a modern audience of teachers, students and general readers.

My favourite parts tend to include the hilarious misadventures of Sun Wukong, aka Monkey: the irate primate ticking off the 10 kings of Hell, the fantastic farce of his release from the prison beneath the Mountain of Two Frontiers, and Monkey trying to free an entire city from tyrannical Taoists.

Perhaps the funniest and sharpest chapters are those set in the Land of Women, where the book’s male quartet are taught various eye-opening lessons by the challenges facing their female counterparts. The most eye-opening (and certainly the most eye-watering) are the mystical pregnancies that befall Tripitaka and Pigsy after they drink from the Mother-and-Child River.

If proof were needed of women’s superior toughness, Pigsy has hardly felt the first contraction before he is screaming, “Doom! I’m doomed!” and demanding to drink the water of the Abortion Spring. It’s a shame a similar trial of masculine empathy can’t be arranged for the members of the American Supreme Court who just overruled Roe vs Wade.

8. Atomic Habits, by James Clear (Penguin Random House Business, 2018)

If all this talk of change has given you a taste for changing your own life, there aren’t many better places to start than James Clear’s bestseller Atomic Habits. Clear has been writing about habits for a decade now – how bad ones are formed, and how good ones can be created.

His underlying thesis, which is built on personal experience and wide-ranging research, is that habits are the result of small (or “atomic”) actions repeated regularly for a sustained period of time. “If you can get better 1 per cent each day for one year, you’ll end up 37 times better by the time you’re done. Conversely, if you get 1 per cent worse each day, you’ll decline nearly down to zero.”

The problem facing most of us is that such incremental changes, good or bad, take time to bed in. “If you study Mandarin for an hour tonight, you still haven’t learned the language.” The same delusion applies to bad habits: “If you work late and ignore your family, they will forgive you.”

Clear’s manual for making genuine change has four main laws: make it Obvious, Attractive, Easy and Satisfying. This will encourage you to repeat the change time and again. In short, make it a habit.

I have read Atomic Habits and listened to Clear’s somewhat percussive audiobook. In either case, the basic text comes with all manner of extras (journals, cheat sheets and advice tailored to business and family).

9. Climate of Change (Podcast) with Cate Blanchett and Danny Kennedy (Audible Originals, 2022)

Although not strictly a book, the Climate of Change podcast I mentioned at the beginning is well worth a listen this summer. Cate Blanchett and Danny Kennedy talk to politicians, academics, scientists, activists and even Prince William about initiatives to combat climate change.

The most inspiring encounters include a conversation with Jeraiza Molina, who is helping night fishermen in the Philippines use sustainable batteries to power their lights. Then there is Brett Isaac, who is attempting to introduce solar power to the Navajo Nation.

In the final episode, musicians, artists and filmmakers ponder how culture can help change behaviour. The matey good humour of the hosts keeps things lively, but they also know when to get serious.

It is likely too much to expect any book, even ones as good as these, to dispel the apocalyptic mood of the moment. But whether you dive into a madcap children’s fantasy from 1865 or search for mystical patterns in a 3,000-year-old Chinese divination manual, feeding your imagination, no matter where you spend the summer, seems as good a way as any to nurture inner calm in the state of near-surreality that is 2022.