- After a long land battle left the natural environment around remote Sha Lo Tung scarred, naturalists are stepping in and wildlife is returning. For now

Although Hong Kong’s bucolic Sha Lo Tung area is less than 4km (2.5 miles) from the bustle of Tai Po Market – a satellite town of high-rise residential blocks and shopping malls in Hong Kong’s northeastern New Territories – the only road in is narrow, angling up a wooded hillside before curling around into a small valley, ending just above a burbling stream.

The basin floor spreading out from either side is undulating, and a worn track leads past a fence marking the boundary of an organic farm.

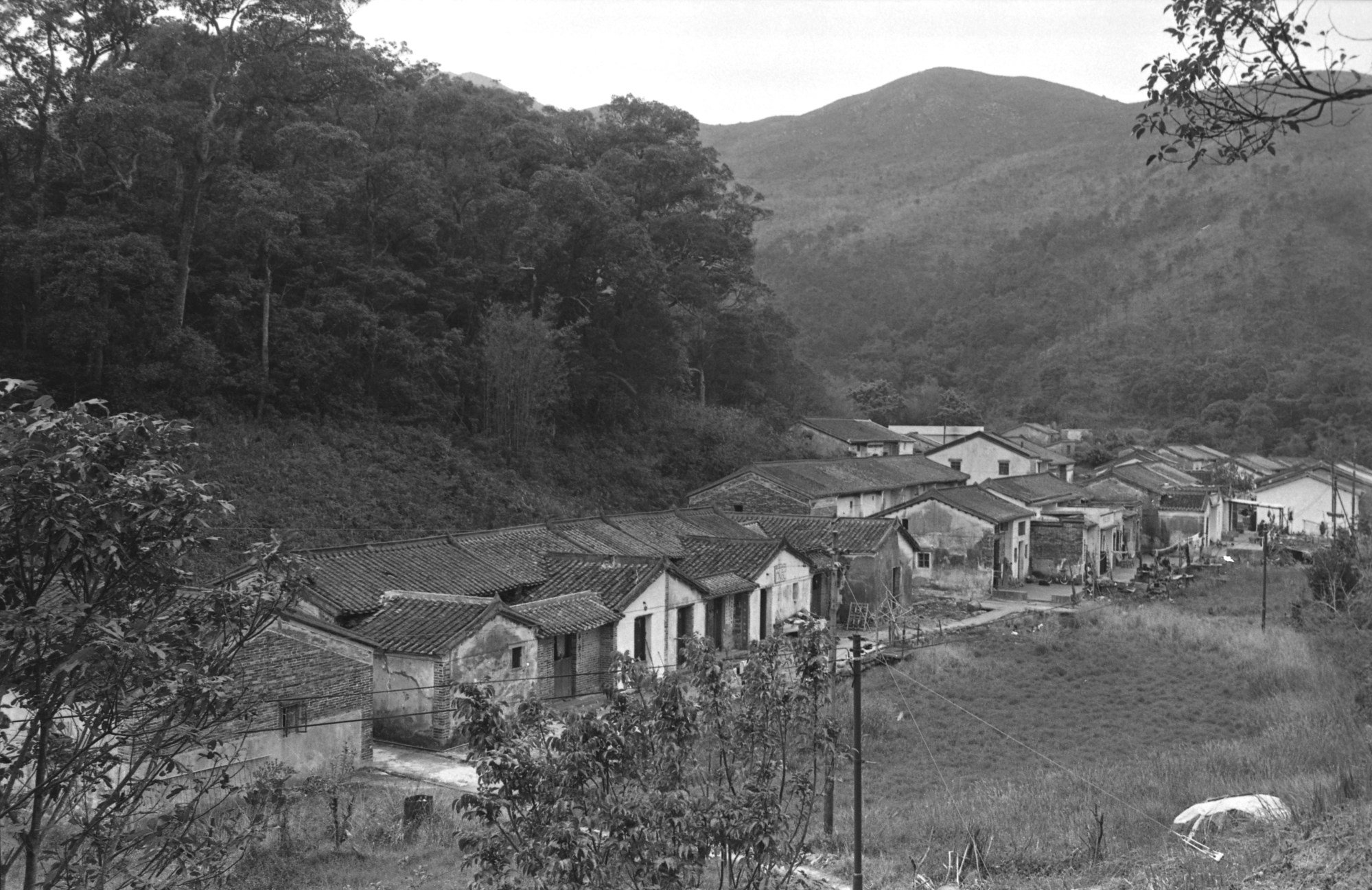

Nearby, a fading information board introduces six of the butterfly species found at Sha Lo Tung, and a couple of minutes beyond, the dirt road ends at the village of Cheung Uk, where around 50 houses cluster beneath a tall forest.

These are small, mainly in the village style typical of rural Hong Kong before the 1970s, each with an indoor living space and a loft for sleeping below the roof. No one lives here now, and most of the houses are in varying stages of decay, with roofs collapsed, brick walls crumbling.

Walk past the first couple of rows, and you might have to look beneath resurgent vegetation to find the ruins of buildings abandoned decades ago.

Next to dilapidated Cheung Uk, recently created pools with marshy margins are tended and fussed over by a small team of workers, with the aim of attracting an increasing variety of wetland wildlife.

Even on an early winter’s day, when most insects are inactive, two small dragonflies known as common blue jewels fly close together in an aerial skirmish, competing for territory.

How bucolic it is, yet this tranquillity belies Sha Lo Tung’s former role at the centre of fierce disputes spanning four decades. As a South China Morning Post article titled “Trouble in paradise” noted in June 1995, “of late the sleepy hollow has come to resemble something of a battlefield”.

The threat of development loomed for decades, with plans that would have resulted in a very different Sha Lo Tung today, complete with an expansive golf course overlooked by upmarket housing blocks.

After a lengthy saga, the plans were stymied and, following a land exchange in 2022, the new pools for marine life, as well as the organic farm, have been healing some of the wounds inflicted on the natural environment.

The saga of Sha Lo Tung has starred a cast of humans including villagers, wannabe developers, nature lovers and green groups, consultants, and off-road vehicle enthusiasts; along with small yet highly influential dragonflies.

There are at least three differing reports of the year villagers first settled in Sha Lo Tung, though perhaps the most trustworthy of these is 1689, as stated in a 1999 letter to the Post from three village representatives familiar with their clans’ histories.

That was just two decades after the area that is now Hong Kong, along with much of China’s southern coast, had been an exclusion zone, after the newly triumphant Qing dynasty sought to boost its security against remnant Ming forces based in what is now Taiwan.

The Hakka – “guest people” – had originated in the Yellow River valley, in mainland China, but migrated south over time, mostly farming for a living. Arriving in Sha Lo Tung, they cultivated rice and vegetables, and reared ducks, chickens and pigs. To create rice paddies plus a network of irrigation channels, they remodelled the landscape.

For almost three centuries, Sha Lo Tung remained an unremarkable place in the annals of Hong Kong.

This decline was especially marked during the 1960s. With farming tough here, away from the productive soils of floodplains in northwest Hong Kong, villagers left to work in urban areas, or headed for new lives overseas, especially in Britain.

By the mid-1970s, only a few dozen elderly residents remained and, in 1978, much of the land around and especially east of Sha Lo Tung was designated as Pat Sin Leng Country Park. The future looked peaceful, yet as elsewhere in Hong Kong, the village areas were excluded from the country park, supposedly so that rural lifestyles could continue, leaving open the possibility of other uses.

Enter the Sha Lo Tung Development Company, established in 1979, which over the years has concocted several plans for the basin.

The company approached villagers and purchased rights to use most of their land, in return for a HK$150,000 deposit for each house plus money for land, and a promise that once the development was finished, each villager could trade in the deposit in return for a house they could live in or sell.

Undeterred, the company expanded its plan, adding a clubhouse, luxury housing and more. In 1983, this received in-principle approval from a Lands and Works Conference.

Seven years later, the fate of Sha Lo Tung perhaps appeared sealed, after the Country Parks Authority gave the thumbs-up to plans for a development that would include 31 hectares of park land fringing the Sha Lo Tung basin.

The Lands Department looked set to follow suit, provided the company addressed concerns regarding an environmental impact assessment.

We’ve done quite a lot; it seemed like mission impossible here. The government had no idea what to do with Sha Lo TungKenny Li Hon-man, a Sha Lo Tin villager helping to build an organic farm in the area

But six environmental groups launched a crusade against the Country Parks Authority’s decision, arguing that golf is an elitist sport and public access would be restricted.

One of these was WWF-Hong Kong, which in 1991 published a newsletter with an article titled “The Rape of Sha Lo Tung”, suggesting the golf course was a clever ploy to enable luxury housing development.

Environmental NGO Friends of the Earth applied for a judicial review of the Country Parks Authority’s decision, which was then quashed by the High Court.

In 1993, the Commissioner for Administrative Complaints (later titled the Ombudsman) upheld a complaint of maladministration against the Country Parks Authority.

The Sha Lo Tung Development Company responded by revising the plan to exclude country park areas and downsizing the golf course from 18 holes to nine while also boosting the planned housing. Yet the project remained elusive.

“We have demanded the village be built now and we want compensation for the years our people have been paying rent,” said Sha Lo Tung villagers’ representative, Roger Li Kwok-keung, a villager who was by this time an accountant living in England.

“We have given the developer until the end of the year to do these things or we will take back the village.”

The following year, 1995, saw bulldozers arriving, with shrubs and trees removed and land stripped bare, supposedly for organic farming. But no farming took place, no village was retaken. Sha Lo Tung fell quiet once again.

Though the golf course was dropped from the plan, the High Court refused to overturn a conservation order stopping the developer building 160 homes at Sha Lo Tung.

The head of Cheung Uk village, Cheung Tin-fuk, expressed dismay, telling the Post, “If the dragonflies and butterflies don’t like the development, they can fly away.”

Further environmental impact assessment work followed, including a project for which I spent three days surveying birds at Sha Lo Tung in July 1999.

One afternoon, I met Joseph Fong Tsung-hun, director of the Sha Lo Tung Development Company, and he was forthcoming until I remarked, “Well, you do own one of the best areas for biodiversity in south China,” after which he walked away to his car.

While major development plans had been thwarted for the time being, Sha Lo Tung was not safe from harm.

In 2012, the Sha Lo Tung Development Company was back with a new plan, this time including a 60,000-niche columbarium in partnership with a former opponent, environmental organisation Green Power. Surely this would placate the greenies? Alas for the developer, not so.

Evidently unruffled by the unfilled promises to villagers, and multiple wild creatures losing their homes, he observed, “We are the biggest victim.”

Fong was perhaps unfortunate that, thanks in part to the dragonflies, the area where he saw opportunities in the ’70s had become Hong Kong’s second highest priority site for nature conservation, after the Deep Bay/Mai Po area; yet unlike at Deep Bay, the government refused to step in and buy land.

But in his January 2017 policy address, then chief executive, Leung Chun-ying, announced a potential way forward, by offering the developer a rehabilitated landfill in exchange for its holdings at Sha Lo Tung.

At last, the future for Sha Lo Tung looked bright. “Negotiation and compromise can lead to a happy outcome for all,” a Post editorial enthused in 2017.

But not for all, not in Sha Lo Tung anyway: in 2018, a villager sued the developer in a bid to force it to honour an agreement to build two houses, and Green Power filed a writ in the High Court seeking an injunction against five men – all surnamed Cheung – to ban them from entering the conservation site and intimidating its staff.

It seems the injunction worked, enabling Green Power and its contractor to create a small wetland area beside Cheung Uk. This features a main pond perhaps the area of a tennis court, with plastic pipes leading to a handful of smaller, shallower pools below.

The earth banks and piping look simple, yet the project has so far cost several million Hong Kong dollars in government funding, and involved Green Power negotiating a tangle of red tape.

During a visit to the site, Green Power director Dr Cheng Luk-ki tells of the landscaping work requiring Town Planning Board approval, and the challenges in even creating a small irrigation channel from a nearby marsh.

Given the sensitivity of Sha Lo Tung, the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department closely oversees plans with the aim of preventing adverse impacts by the project.

“We’ve planted native species like plants found nearby,” says Cheng. Wildlife surveys by Green Power indicate the effort to create wetlands in an area that had dried out are paying dividends, with the presence of dragonflies, including two species that had not been recorded for six years.

While the management agreement ended in July last year, the government is providing further funds so that Green Power can manage the new wetlands, and create more.

Sha Lo Tung Greenfield is spearheaded by Kenny Li Hon-man and Celia Chan Lai-ha, who I speak to in a wooden shelter surrounded by vegetable plots. Li, 62, is a native of Sha Lo Tung, and remembers his early childhood years here.

“I started to help my mother with farming when I was five or six; I even had a cow when I was a little kid,” he says. Li’s family emigrated to Britain when he was 14. After school and university he returned to Hong Kong, where his work included setting up an IT firm, along with stints in mainland China.

On retiring, villagers invited him back to Sha Lo Tung as their representative, partly to help oversee the land exchange. “If they think me capable, why not?” he decided – after all, it was always his aim to live here after retirement.

“We’ve done quite a lot; it had seemed like mission impossible here,” says Li. “Other than finishing the land exchange, the government had no idea what to do with Sha Lo Tung. We inspire them, saying people can move back, and live with nature, receiving training in organic farming from Celia.”

Chan is a former colleague of Li’s. Hailing from urban Hong Kong Island and, with a corporate career background following a degree in human resources management, she might seem an unlikely person to teach organic farming. But she always loved hiking and the outdoors, and was working at Li’s company when he returned to the office one Monday looking tanned.

“Have you been sunbathing?” she asked, and when he told her about Sha Lo Tung, Chan decided to see for herself, leading to her become so fascinated with the work there that she became an organic farming inspector after taking a course at Baptist University.

“Organic farming is not for making money – in the long run, it’s for the good of the soil, avoiding problems with fertilisers and herbicides,” says Chan, who is now at Sha Lo Tung full time, albeit while consulting part-time via email and phone calls.

Chan and Li outline how they have developed the farming project with little funding, struggling to build such things as two solar power stations, and installing pumps to source stream water. Currently, perhaps 70 per cent of the people working with them are from outside Sha Lo Tung.

“The DNA of village people is materialistic, many will only work for money,” says Li. “I can’t convince all the villagers to join, except 10 or 20 who like this project as much as I do. We started with three villagers, and word has spread.”

Chan rallied volunteers by contacting former classmates who were nearing retirement, some of whom arrived with strong backgrounds, such as university professors, and helped with installing and repairing equipment, figuring how to collect rainwater and seeking government permission for various projects.

“I also joined a Facebook group about farming, and invited members to come here,” Chan says.

Now there is a pool of around 90 volunteers. Perhaps unsurprisingly on this “battlefield”, Li remarks that working side by side with Green Power has not always been easy, with arguments during the first two years, but he now appreciates the ways Cheng and colleagues can help by evaluating their efforts.

“I’ve been to England, met [former Sha Lo Tung] villagers there, and told them, ‘Green Power is not your enemy – you can consider them as your gardeners’,” he says.

Although Li waxes lyrical about harmony with nature, the farm has a small electric fence to keep out wild boar, along with dogs that occasionally kill boar. I point out that this is hardly harmonious, to which Li responds, “The wild boar can move back to nature.”

Even so, I notice birds such as olive-backed pipits feeding in the farm, and Li says, “This is the first example in Hong Kong of a green group and villagers working together in harmony.”

While some might quibble with this, he hopes the groundwork has been laid in order to convince the government to allow further small-scale development in Sha Lo Tung.

“Now, we are only using about a 20th of the old farmland,” says Li. “If we can expand a little, it will be the best way forward.”

Helped by around HK$1.5 million (US$190,000) in compensation paid by the Sha Lo Tung Development Company to families who had sold their development rights, Li hopes it will be possible to rebuild about 12 houses, with nine of them forming an eco village.

That’s easier said than done, of course, with challenges including waste treatment so that streams are left unsullied. But Li is optimistic. “We need more flexibility and support from the government,” he says. “If they are brave enough to say yes, we will do more to make Sha Lo Tung look even better.”