- Hong Kong choreographer Yuri Ng was six when he had his first dance lesson, and has not looked back since. He talks about keeping his creative juices flowing

My father took over the family business, a light bulb factory in Causeway Bay, Hong Kong but in fact he was an actor. He began doing stage acting and was then a television actor, comedian and game show host and even did a bit of film, all while running Kwong Wah Lamps.

I was born in Hong Kong in 1964 and am the eldest of three – my brother is 18 months younger, my sister 10 years younger. We lived across the street from the light bulb factory.

My mum was in education and later became a secondary school principal. I didn’t go to the school where she taught, she was clear that wouldn’t be a good idea.

I went to North Point Methodist Primary School and then to Morrison Hill Primary School and did two years at Lui Kei Government Primary School.

Serious fun

A couple of older cousins studied ballet at the Jean M. Wong School of Ballet in Kowloon. My mother thought it might be a good pastime for me, too.

‘No one asks to become addicted’: when son died she declared war on drugs

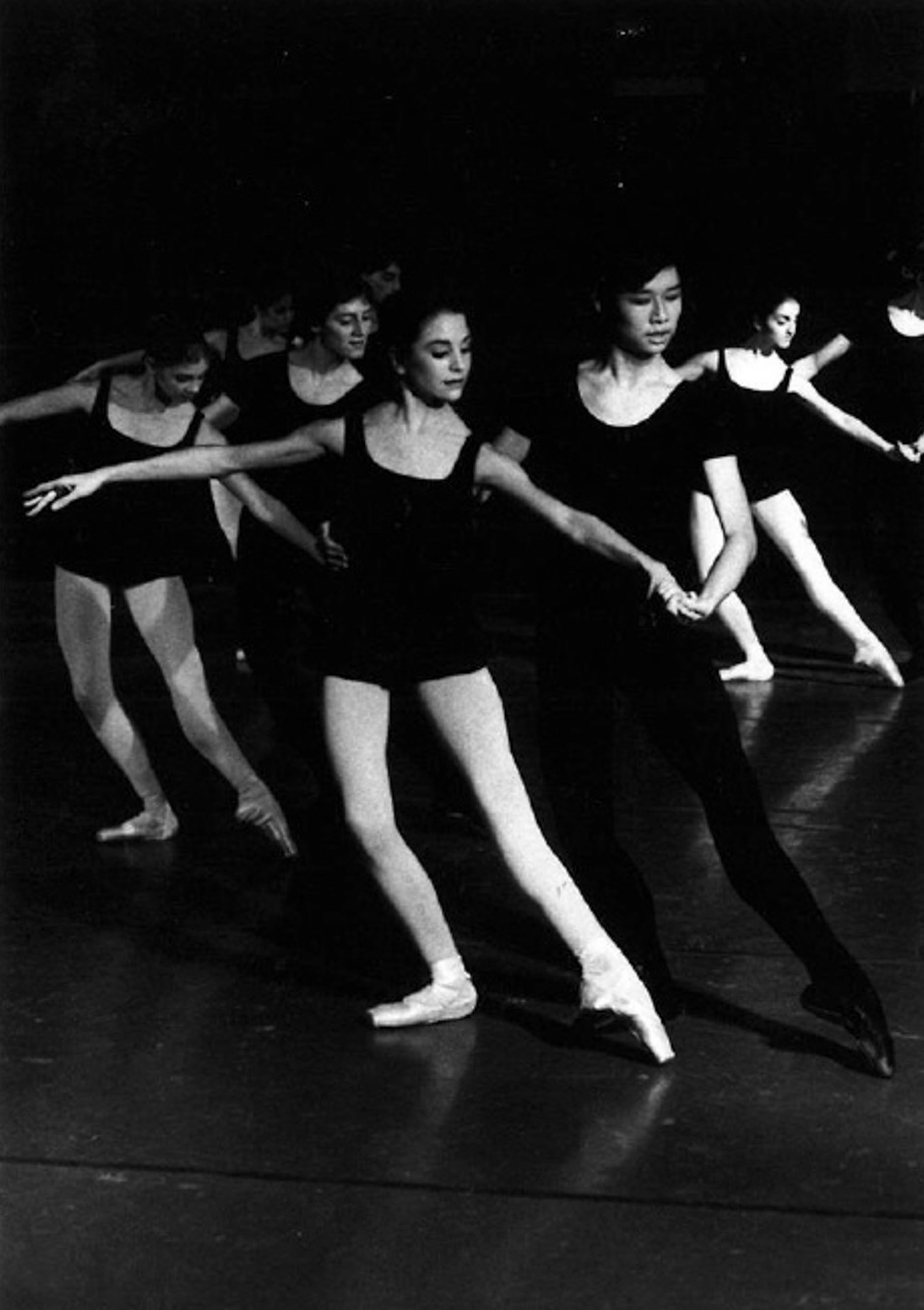

Jean Wong’s had a studio within walking distance from our home, and I started going when I was six years old. I remember Jean Wong putting me on her lap and I felt loved.

She played a big part in my dancing career. She has helped me get scholarships and made introductions to give me work opportunities.

I was one of only a very few boys at the ballet school, it felt like my world. I loved the attention and being praised. For me ballet was never serious. It was serious fun, serious enjoyment.

Just rewards

I went to secondary school at Wah Yan College. My mum didn’t think I’d survive O-levels in Hong Kong and sent me to school in Toronto. We have family there, so I could stay with my aunt and cousins.

I never imagined myself as a professional dancer because there wasn’t the Hong Kong Ballet or the Academy of Performing Arts then. There was only an amateur group organised by ballet teachers, the Hong Kong Ballet Group.

Every year, they would put on an annual production. The summer before I was due to go to Canada, I performed in Sleeping Beauty. To my surprise, my performance was rewarded with a one-year scholarship at the Royal Ballet School in London the following year.

How Tony Parsons blew a year’s salary in a Hong Kong bar yet kept returning

Too advanced

I went to Toronto and immediately enrolled in a ballet school run by Mrs Marian Macpherson. A teacher at the school, Ms Janice Alton, said I was too advanced for the school and organised for me to audition at the National Ballet School in Toronto.

She did all the introductions and arranged for my audition, I’m very grateful to her. The National Ballet School took me on as a full-time student.

They were so supportive, I stayed in the residence and took ballet lessons daily alongside academic classes. It was exciting to be away from home. Everything was new – speaking English, the food, dancing all the time.

No Asians

Meanwhile, inflation and other factors meant the scholarship money I’d won in Hong Kong was only enough to cover the school fees in London and not my living expenses.

My mum asked if they could raise funds for another year. They did and that’s how I ended up spending two years on a scholarship in Canada and then went to London.

London was amazing. Shoichiro Sadamatsu from Japan and I were the only Asian boys at the school. I had a reunion with him more than 20 years later in Kobe and I made a ballet for his ballet company.

I was awarded the Adeline Genée Gold Medal by the Royal Academy of Dance. At the end of the year, everyone had to look for a job. The school principal advised me not to stay in England, he said I wouldn’t be accepted – the Royal Ballet in the 1980s wouldn’t take Asians – so I got a job in Canada, which was much more multicultural.

‘Peer support is hope’: how a charity helps people cope with grief

Goofing around

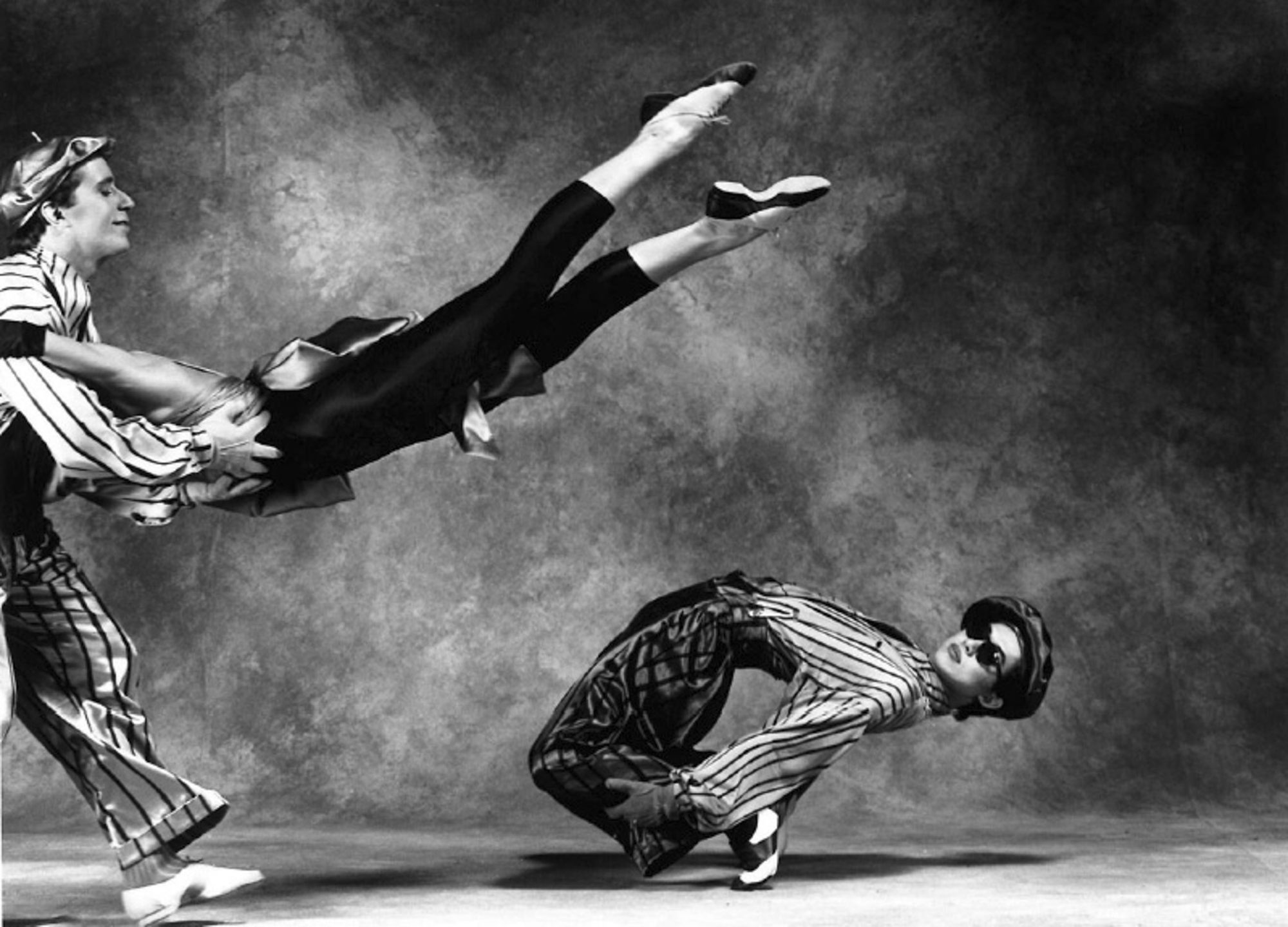

In 1983, I joined the National Ballet of Canada as a dancer. The new artistic director was Erik Bruhn, and everyone was excited about working with him.

He was keen on bringing in contemporary choreographers. We were introduced to some weird ways of working, which we hated at the time, but it was a great experience.

The Canadian choreographer Danny Grossman brought a case of beer to the studio for afternoon rehearsal and encouraged us to drink. It made him and most people more relaxed, but I didn’t drink. I was able to relax without the alcohol and he saw something unique in me and used it in the show.

It was the first time I realised I could do some crazy stuff, some goofing around, and people liked it.

When you are 25, your body starts to change. There are always younger, more daring bodies coming upYuri Ng

Bed hopping

The company encouraged young dancers to choreograph and I always said yes. I enjoyed doing something outside the daily routine. I fell in love with one of the principal dancers, he was 24 and Italian. It was my first big infatuation.

Being gay in the dance community was nothing unusual. The company was quite incestuous. When we came to tour and they asked about the room situation, each time they had to ask again; they couldn’t assume couples were still together.

Once ‘a shy kid’, now he’s a comedian on Netflix: meet Amit Tandon

Hitting 25 hard

When I was 25, I left the National Ballet of Canada and spent a year in Montreal with Les Grands Ballets Canadiens. I thought with a smaller company there would be a chance to dance more, but it wasn’t a happy experience. I injured my foot, but still had to dance.

That period hurt me more emotionally than physically. I was feeling old. When you are 25, your body starts to change. There are always younger, more daring bodies coming up. I had to find a way to face my future after dancing.

I spent three years freelancing in Toronto, which was when I came across collaborators and artists and did choreography and costume design.

Mahjong ballet

In 1993, my father was sick, and I returned to Hong Kong. Even on his deathbed he was still giving me dramaturgical advice.

He was a keen mahjong player and for years had been telling me that mahjong was a good theme for ballet. You have 14 dancers in matching pairs – north, east, south, west. He talked about mahjong in terms of relationships, chance and taking risks.

I’ve been with my partner for eight years. He’s 31, much younger than me. That age difference allows me to see a different generationYuri Ng

A month after I returned, he passed away. I stayed on in Hong Kong. Jean Wong gave me work, choreographing for students at my old school. In 1993, I did my first commission with City Contemporary Dance Company (CCDC) and did the mahjong ballet A Game of ____.

It was fun working in Wong Tai Sin with CCDC; I felt wanted again. They were welcoming and gave me a lot of encouragement. I got a lot of opportunities from CCDC, choreographing films, musicals and plays.

I opened a dance course at my old school, Wah Yan College. In 1995, I took some of the students to the school dance festival and we won. It was a big thing for a boys’ school to enter a dance festival – and win.

A Plastic Ocean director Craig Leeson on changing the world through film

Going pro

I’d been thinking for some years about creating ballet music using only the human voice. Our first performance was called Rock Hard (2008) and was based on a story around Hong Kong’s Amah Rock.

It was a hit and we were encouraged to keep going. We toured the show and applied for a grant, and in 2012 formed a full-time professional company, the Yat Po Singers.

What is my function?

I’ve been with my partner for eight years. He has a PhD in Chinese history and is a university researcher. He’s 31, much younger than me. That age difference allows me to see a different generation. He helps me think differently and challenges me: “Why should I come and see your show? What has it got to do with me?”

He challenges me to consider the role of the dance choreographer or art maker. What is our function in society? In the performing arts, besides putting on a nice show with full capacity, we don’t tend to ask those kinds of questions.

When I see a show with him, we try to look at it not just from a technical point of view, but to consider what the director was thinking.

How National Geographic magazine changed eco-filmmaker Craig Leeson’s life

Many milestones

Next year is a year of anniversaries: Jumping Frames, our movement image festival, will turn 20; the CCDC dance centre will turn 30; the CCDC will turn 45; and I will turn 60.

I’m still exploring ways to create. I’m the artistic director of a dance company, so naturally people expect that I should make dances. I feel I need to create. I don’t need to make dances. I like to make things with my hands, with needle and thread or gluing things together or pottery. I like to make costumes from discarded clothes.

Creative thinking

This is a creative time for Hong Kong. When whatever you say can be banned easily, when you want to overcome it, you are naturally creative.

I wish people didn’t separate dance, Chinese opera and drama. I want to bring them all together. When is a dance not a dance? When is music mere sound? Or when does sound become music? I don’t believe in separating; we are all makers of things.

If we can lower some of our ego, we can communicate more. I want us to be able to come together and talk things through and find solutions together.