Language Matters | The foreign words that make it to the Oxford English Dictionary – and food for thought about some Asian words that haven’t

If words such as restaurant (originally French) and pizzeria (Italian) have been absorbed into English, what will it take for dai pai dong and bing sutt to become trendy enough to follow them?

Which of these words are you happy using in English? Restaurant, brasserie, deli, cafeteria, pizzeria, panciteria, kopitiam, dhaba, cha chaan teng, dai pai dong, bing sutt?

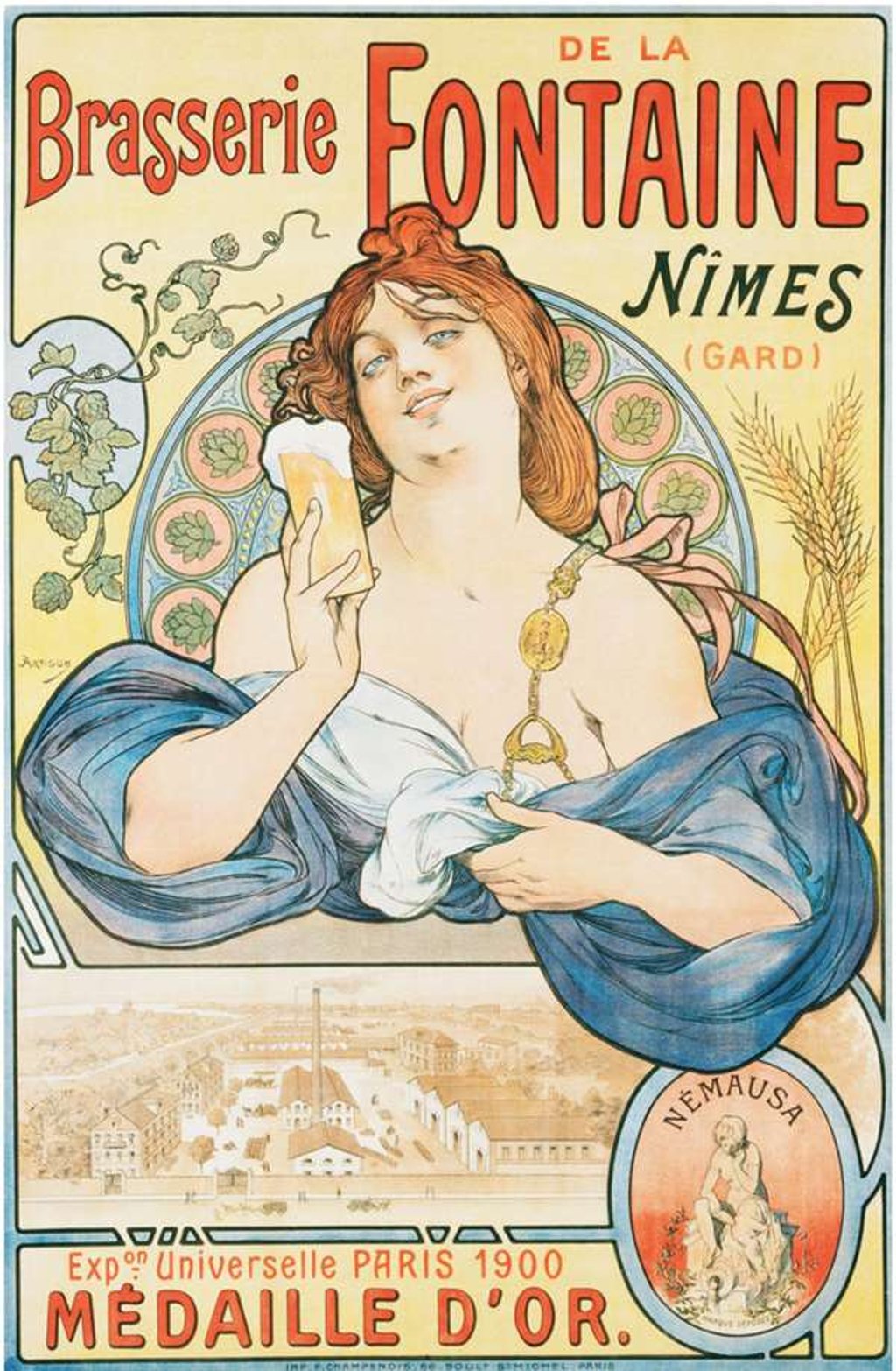

No to the latter six, because they’re, well, not English? But wait: “restaurant” is originally French, having entered English in the late 1700s, as is “brasserie” (late 1800s). “Pizzeria”, naturally Italian, arrived in America with immigrants in the early 1900s. “Deli”, first documented in mid-20th-century American English, is clipped from “delicatessen”.

You see where I am going with this. If we have no issue with cafeteria or pizzeria being part of the English language, then by the same token, why not panciteria? Denoting Chinese restaurants in the Philippines, pancit comes from the Hokkien 便 ê 食 piān-ê-sit (“ready-made food”) – the majority of Chinese hawkers catering to colonial Spanish Philippines working women hailed from Fujian province. (Pancit’s meaning later narrowed to “noodles”.) Indeed, the ubiquitous Singapore/Malaysian “kopitiam” (“coffee shop”)

and South Asian “dhaba” (“roadside stall”) have roots in other languages – the Malay kopi (“coffee”), Minnan tiàm (“shop”), Punjabi/Hindi dhābā – but are in the Oxford English Dictionary.

Most Hongkongers will have a favourite cha chaan teng or dai pai dong. The latter term has had enough currency in English that it was included in the Oxford English Dictionary’s 2016 update. This is the point: use a (borrowed) word often enough and it will soon be adopted by the language. Just as “restaurant” was three centuries ago. So it is gratifying to find local airlines serving “Cha chaan teng cookies”, or encounter outlets such as Pak Hailam’s Kopitiam (“Father/Uncle Hainan coffeeshop”) and Hong Kong Bing Sutt – not only in home towns Malaysia and Hong Kong, but further afield, too.