Then & Now | Opinion: how Hong Kong’s political rot started in the 1990s, and the rise of Joshua Wong and his sort

With role models such as ‘Long Hair’ Leung Kwok-hung and ‘unbearably loud’ Emily Lau, it’s no surprise Hong Kong’s millennial political hopefuls are resorting to juvenile antics

Monkey see, monkey do, as any schoolteacher knows only too well – and Hong Kong’s youthful protesters have had plenty of simians-in-office to emulate in recent years.

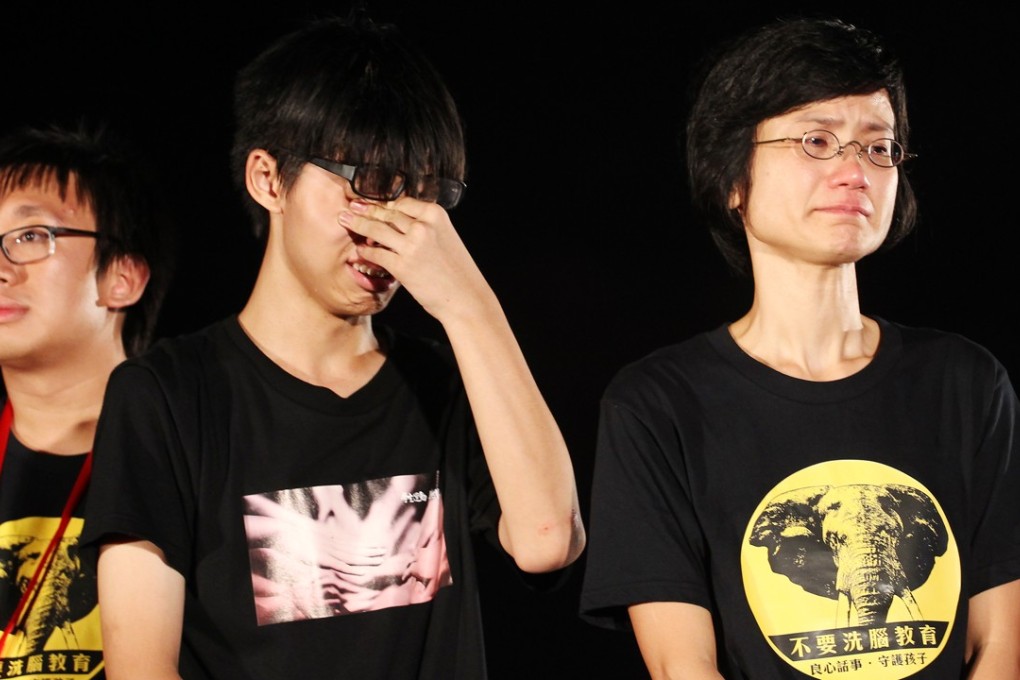

During the 2016 Legislative Council election, several of the older cohort climbed back into the branches to make way for younger and even more cantankerous political hopefuls.

Saturation media coverage further encourages juvenile antics, which are just one more example of Hong Kong’s mindless copying of lamentable overseas trends; in the 1990s, Korea and Taiwan made rowdy transitions to more mature political systems. Now it’s Hong Kong’s turn to yodel tunelessly into the political karaoke machine’s tinny, feedback-prone microphone.

From early childhood, Hong Kong’s millennial legislator-activists have observed some pretty doubtful role models. Foul-mouthed ravers (we know who they are) who fling drinking glasses, bananas, slices of luncheon meat, cardboard microwaves and such like, along with crude epithets and ranted slogans, have dominated local political life – and news headlines – ever since the handover.

In earlier times, strident public viewpoints were better expressed. Elsie Elliott (later Tu), Brook Bernacchi, A. de O. Sales, and other elected members of the Urban Council (disbanded in 1999) seldom minced their words – as verbatim records from council sessions make clear. Nevertheless, they remained polite. The rot began in the early ’90s, with legislators such as the shrill-voiced Emily Lau Wai-hing (privately dubbed “unbearably loud” by the plain-speaking Tu) and Hong Kong’s ubiquitous, all-purpose rowdy “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, who was eventually elected in 2004.