Then & Now | Colonial stayers-on in Hong Kong: will permanent residency always be theirs? History suggests not

Residency status in post-colonial societies is never set in stone; a new sovereign power will always insist on the right to change its mind for reasons of political or economic expediency

Most post-colonial societies allowed former colonials who wanted to stay on to do so, and formalising such provision was a key part of independence negotiations. As the large number of ex-colonials of various ethnicities still resident in Hong Kong indicates, not everyone packed up and went “home” (wherever that might once have been) when the British flag was lowered in 1997.

In the case of the subcontinent, numerous British residents were still scattered across India and Pakistan well into the 1980s. Today, however, more than 70 years after Indian independence in 1947, few Raj-era survivors remain.

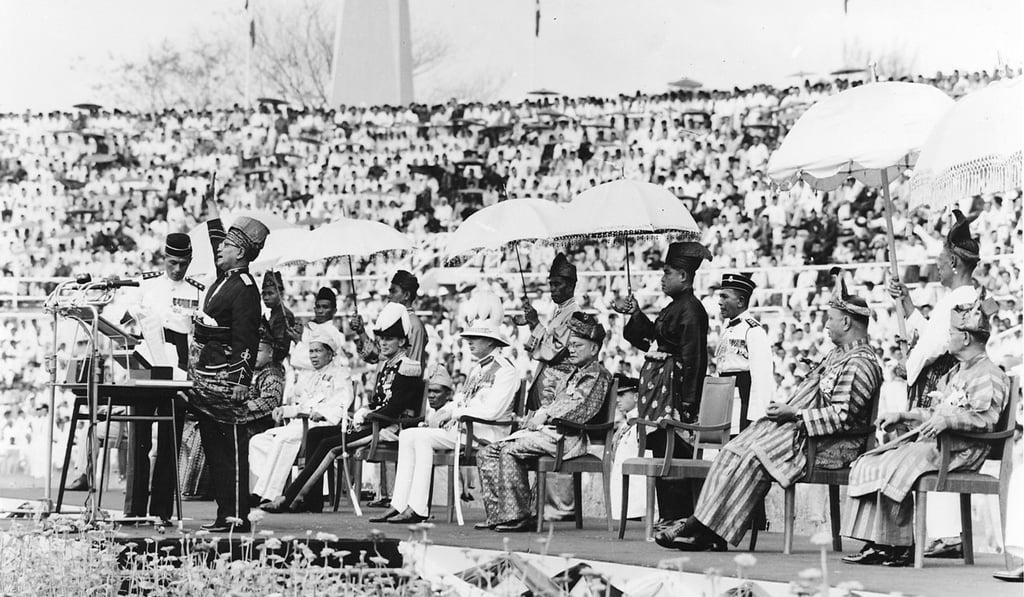

In Malaya, British citizens ordinarily resident there, and who were in the country on the night of independence, in August 1957, were given leave to stay permanently. Some still reside in Malaysia under this provision, and a few became citizens. Permanent residency status later became almost impossible to obtain.

In the years after the return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty, numerous foreign nationals became Chinese citizens by naturalisation. Anecdotal evidence suggests that far fewer have applied in the past five years or so

Residency sometimes continued when a negotiated political transition followed a period of violent insurgency, as happened in Indonesia. When sovereignty was transferred, in 1949, the agreement provided for Dutch civilians ordinarily resident in the former Netherlands East Indies to remain permanently, if they wished. They could also apply for Indonesian citizenship, and many did, but there was no compulsion to do so.