Why Chinese Buddhists, Taoists and Confucians get along yet the world’s Christians, Muslims and Jews cannot

- Followers of the Abrahamic faiths have clashed throughout history, but in China believers in Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism have usually got along

- One reason is that these belief systems are not dogmatic; in the same Chinese temple one can offer devotions to Buddhist and Taoist deities and to Confucius

In a few days’ time, Muslims will celebrate Eid ul-Fitr to mark the end of Ramadan, the holy month in the Islamic calendar. Eid ul-Fitr is referred to by different names or variant pronunciations across the world’s Muslim communities, but these different names all share the basic meaning of a feast day celebrating the breaking of the fast. In Mandarin Chinese, it is called kaizhai jie.

Despite them worshipping the same deity, the historical animosity between the adherents of the three Abrahamic religions has remained insurmountable. This mutual animosity is less a consequence of religious beliefs than the accumulative result of human behaviour throughout history, actions driven by the least attractive aspects of human nature, such as greed, suspicion, tribalism and the propensity for violence.

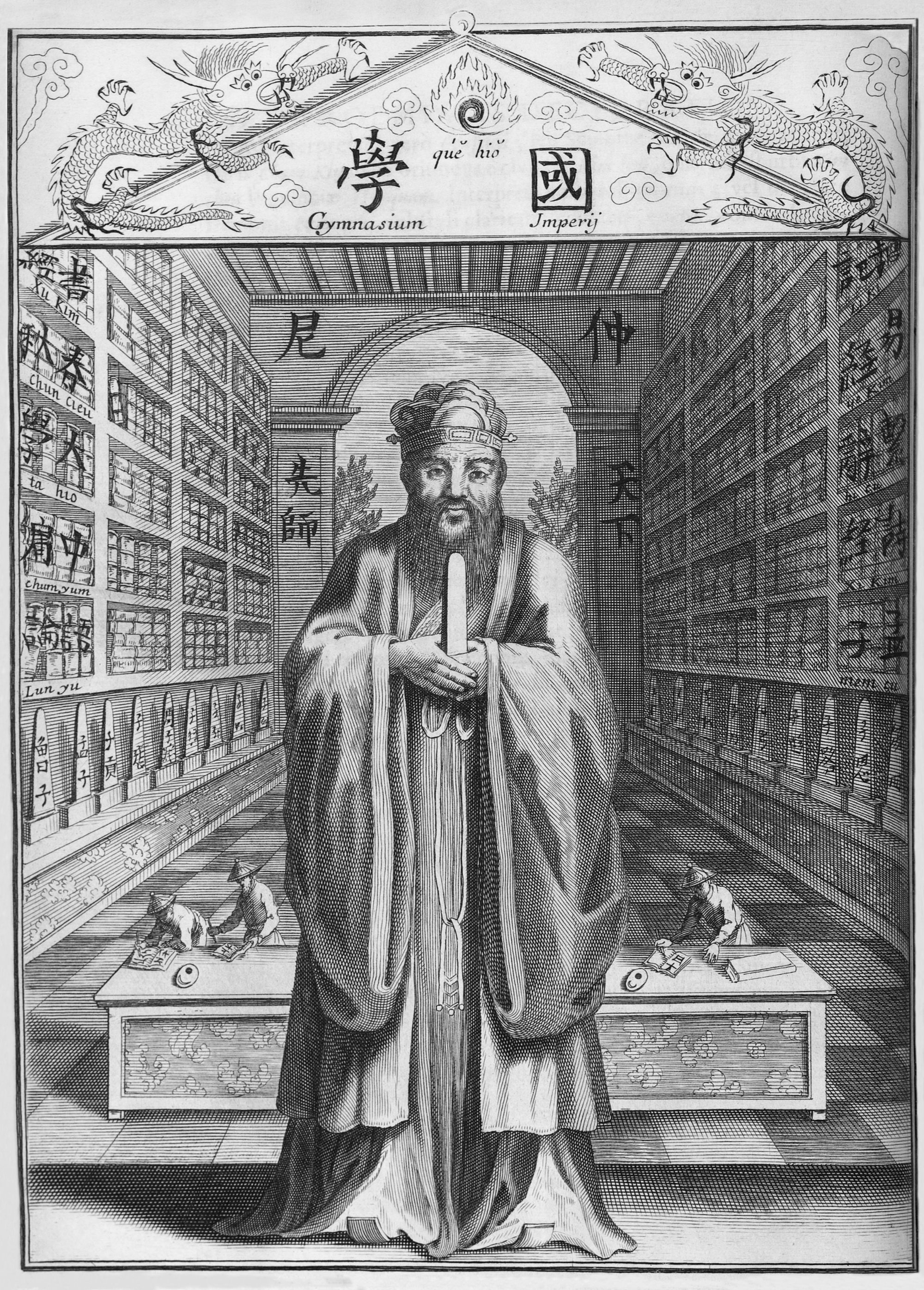

The three main belief systems that have informed the thoughts and actions of generations of Han Chinese to the present day are Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism. Whereas Confucianism and Taoism are philosophical products of the Chinese civilisation, Buddhism first came to China from the Indian subcontinent in the first century CE during the Han period.

Over time, however, Buddhism became so thoroughly assimilated that Chinese Buddhism became a unique and separate religion in its own right.

Compared to Christianity, Islam and Judaism, the Chinese troika of belief systems have coexisted more peaceably. This is not to say that there was no antagonism between Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism. At various times in China’s past, there were instances of religious persecution for the same reasons that different political cliques go to war with one another, but these were exceptions rather than the rule.

Clashes erupt again near flashpoint Jerusalem holy site

A possible reason for the comparatively benign coexistence of Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism in China is because none of them is particularly dogmatic. Confucianism is more a code of human behaviour and ethics than a religion, though it contains supernatural aspects, especially the Neo-Confucianism of the Song (960–1279) and Ming (1368–1644) periods.

Philosophically, Taoism and Buddhism focus more on self-cultivation than the divine. As for their devotional aspects, both religions are famously eclectic and inclusive. Both freely adopt deities from each other’s pantheon, or even beyond, and adapt them according to their own needs.

Walk into any Chinese temple today, and chances are you will find multiple altars dedicated to both Buddhist and Taoist deities. In many cases, they even share the same altar. In some temples, a figurine of a deified Kongzi, traditionally Latinised as Confucius, is also available to receive the devotion and offerings of worshippers.

A typical Han Chinese person today who does not profess any of the monotheistic faiths but who practises some form of religion probably prays to both Buddhist and Taoist deities. They are probably not averse to worshipping animist spirits, even those of non-Chinese origin, as long as it “works”. In their daily lives, they are likely to adhere to some form of Confucian ethics, especially with regards to familial relationships.

Instead of recoiling from the seemingly promiscuous syncretism of traditional Chinese religious practice, we would do well to learn from their disinclination towards dogmatism and exclusion, in religious matters at least.