Moon goddesses through history, from Chang’e in Chinese myth to ancient Greeks’ Artemis, and how homage has been paid to them

- Many mythologies feature moon goddesses, from the Greco-Roman deity Artemis to Chinese mythology’s Chang’e to Davana in Slavic folklore

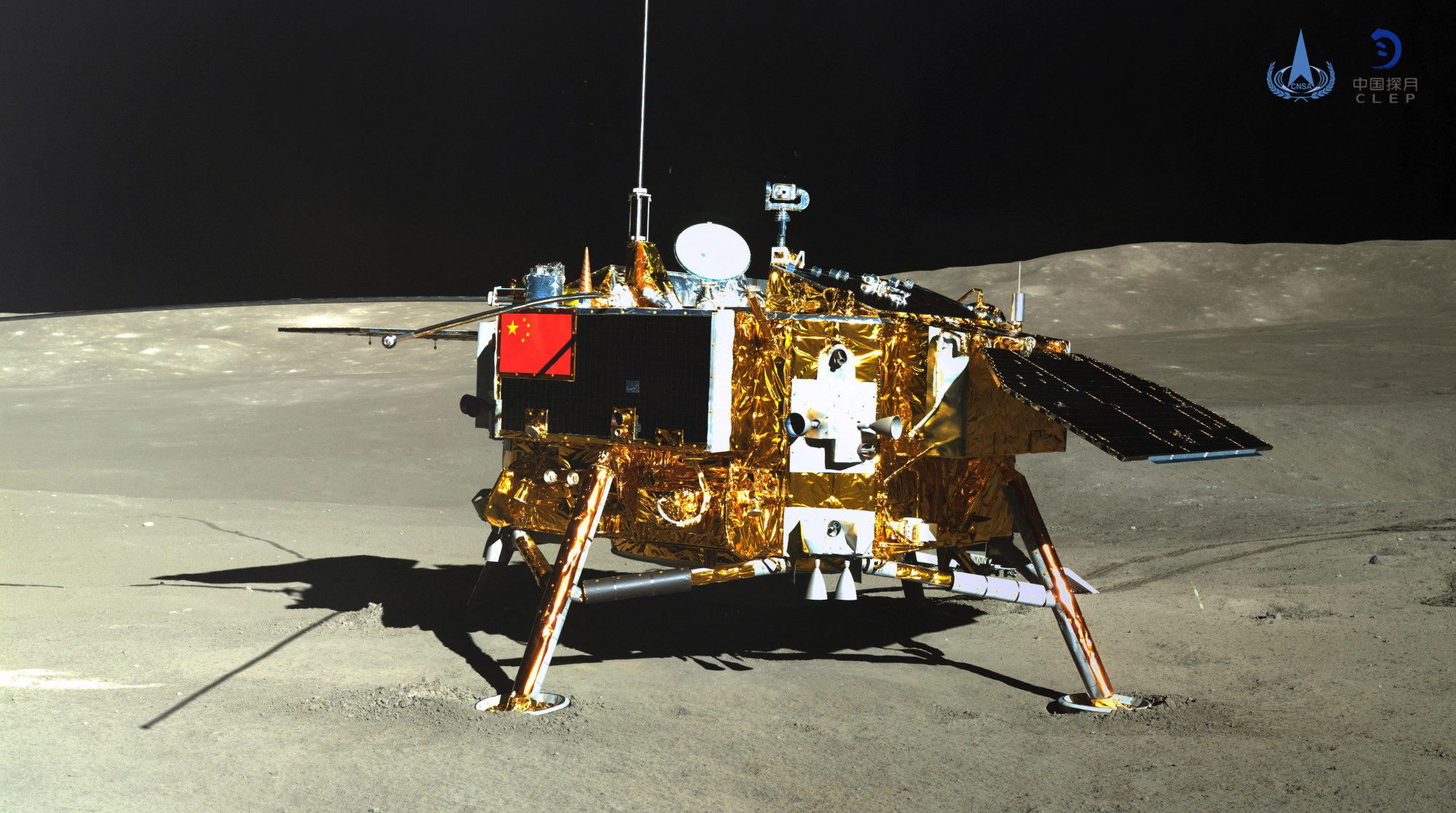

- Space agencies have used their names: Nasa’s Artemis space programme vows to put the first woman on the moon, while China’s Chang’e lunar landings began in 2013

Gaze up at the sky during the Mid-Autumn Festival, and wonder at the moon’s divine significance.

Lunar deities figure in all cultures. While not all are female, many mythologies feature moon goddesses – and homage has been paid to them in several lunar missions.

The Latin lūna – originating in the Proto-Indo-European root *leuk- “light, brightness” – is the name of the divine embodiment of the moon in Roman mythology, Luna.

The Greco-Roman goddesses of the moon tended to be worshipped in a triadic manner. Thus Selene/Luna, goddess in heaven and of the full moon, was associated with Artemis/Diana, goddess on Earth and of the half-moon, and Hekate/Hecate, goddess in the underworld and of the dark moon.

Artemis and Hecate did not originally have lunar aspects, but acquired them later in antiquity through the syncretism common to Greco-Roman religion.

The English lunar, from the Latin lūna, refers to anything associated with the moon, but it is Artemis who has lent her name widely as a moniker.

This is a consequence of Artemis not only being a central figure in Greek mythology, as daughter of Zeus and twin sister of Apollo. (Ironically, this sun god’s name was used in Nasa’s initial lunar programme.)

Where the word moon, and its Indian equivalent Chandra, come from

Artemis is also the virgin goddess of nature, hunting, chastity and childbirth, whose female self-reliance is considered inspiring.

The Soviet Union’s pioneering Luna programme – in 1959 their unmanned spacecraft Luna 2 became the first human-made object to reach the lunar surface – was named after the Russian Луна luna “moon”, inherited from Slavic, also originating in Proto-Indo-European, thus cognate with Latin’s lūna. (The Slavic goddess of the moon is, however, named Devana, equated with Artemis/Diana.)

Closer to home is Chinese mythology’s Cháng’é, who, having drunk the elixir of immortality of her husband, famed archer Hou Yi, took refuge on the moon. It is indeed Cháng’é who is commemorated during the Mid-Autumn Festival.

This goddess’ significance was even more internationally acclaimed with the naming of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Programme missions as the Chang’e series, their first lunar landing taking place in 2013.