The trees and plants in Hong Kong left over from post-war squatter settlements, when 1.5 million fled China’s civil war and Communist takeover

- In the years following the end of the second Sino-Japanese war, 1.5 million people fled China for poor, overcrowded Hong Kong and formed squatter settlements

- Traces of settlements not built over for public housing can still be seen – not least ornamental plants and fruit trees left behind when the settlers moved out

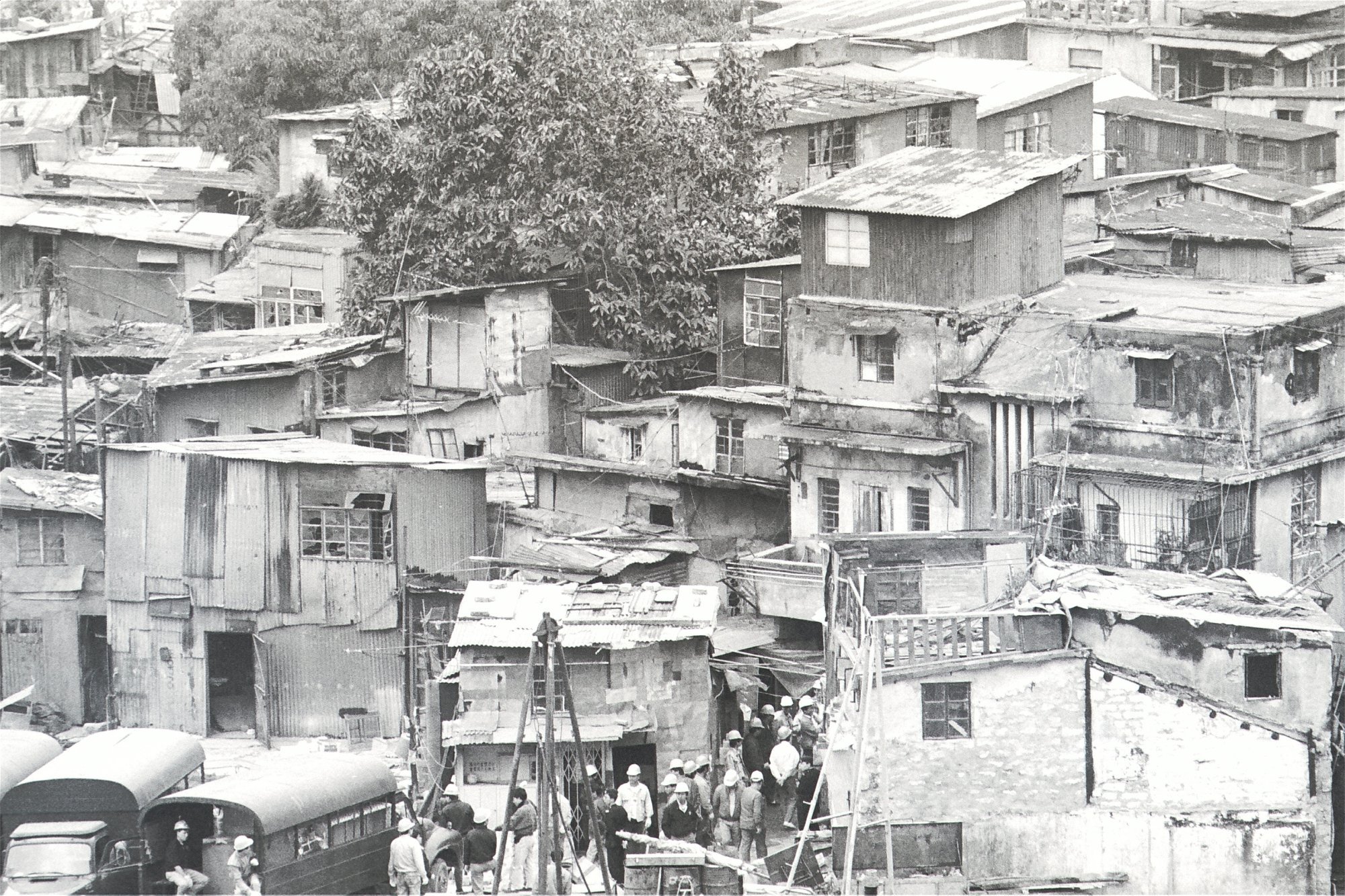

Between 1946 and 1952 – the Chinese civil war having resumed with full ferocity after the temporary pause that the Sino-Japanese war had allowed – more than a million and a half people decamped to Hong Kong, just before China’s emergent surveillance-police state became efficient enough to restrict internal movement.

These mainland Chinese voluntarily chose to make their homes and lives under the supposed oppressions and miseries found in a desperately overcrowded, resource-poor British colony. In direct consequence of this sudden population influx, sprawling squatter settlements became a fact of Hong Kong life, and remained so for more than 40 years.

What happened to these areas – from when the first large-scale squatter resettlement efforts were undertaken in the early 1950s to the construction of public housing developments such as Oi Man at Ho Man Tin in the 1960s and 70s, with integrated public transport, wet markets, medical clinics and schools – are well-documented aspects of local life.

From scholarly monographs on squatter resettlement and public-housing policies to popularly oriented, well-illustrated local histories, along with oral histories and memoirs in both Chinese and English, Hong Kong’s socio-economic evolution in the post-war era can be seen through these distinctive areas.

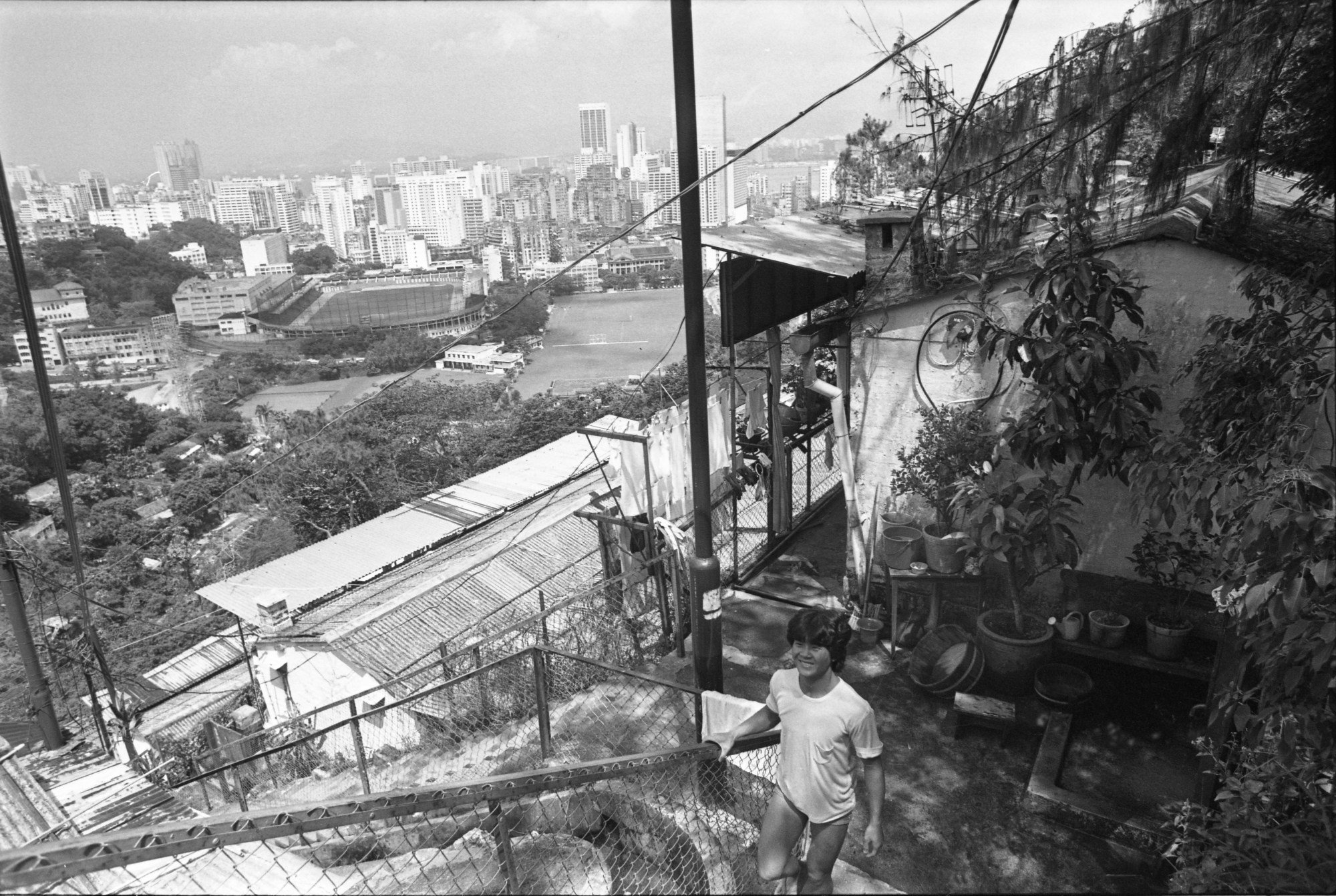

Some fragmentary evidence of earlier times remains in areas where now-demolished squatter settlements were not subsequently redeveloped into public housing estates.

Hidden among long grass and undergrowth, concrete floor slabs – left behind when the rest of the structure was torn down – tell their own silent stories.

While some floors are little more than plain, smoothly rendered cement, others retain expanses of glazed ceramic tiles laid down by one-time occupants to help make their shanty homes more appealing.

Squatter settlement life – especially in larger areas such as Diamond Hill in East Kowloon – was not nearly so transient as non-resident outsiders might imagine; entire lives were led in these areas, and hard-earned money was spent to make dwellings that may have seemed ramshackle and makeshift feel somehow like a permanent home, and not just a place to perch temporarily on the way to somewhere else.

Exotic plants once cherished by squatter settlement residents, that subsequently naturalised into the local environment, also give clues to now vanished lives.

Plants with practical utility were typically tended around squatter settlement areas, where ground space was limited. In consequence, fruits such as lychees, longans, loquats, wong pei (“yellow skin”), along with papayas, bananas and – more rarely – mangoes, can be found.

Ornamental house plants with exotic origins are other commonly encountered botanical escapees. These survivals happened only in places – such as that Lei Yue Mun hillside, or the slopes above Hong Kong Stadium at So Kon Po – where squatter settlements were completely razed, and nothing else was built in their place.

On a recent hike down through one of these long-abandoned squatter areas just above Lei Yue Mun in eastern Kowloon, we spotted – at a distance – some sizeable, healthy-looking tangerines, high up on a spindly tree; interestingly, no fruit was in evidence further down, within easy reach of passing hikers.

At Lunar New Year, know your kumquats from your Teochew sweet oranges

One can only presume that a Lunar New Year tree, bought for its ornamental value at festival time decades ago, had been planted out on a bit of waste ground – instead of being thrown away – gradually became established and had survived, if not exactly thrived, during the passage of the years.

Whoever had planted this tree had long since departed – Lei Yue Mun was cleared more than 20 years ago – but the now-towering tangerine tree remains.