The eccentric, Chinese-reading Hong Kong University English teacher who became ‘everyone’s idol’ in the 1930s, before his untimely death

- Hong Kong University was known for its conventional types in the interwar years but Adrian Paterson, a Briton who commonly wore a Chinese robe, bucked the trend

- The Oxford graduate and fan of Chinese literature was admired for his energy, and he inspired those he taught long after a freak accident in Egypt took his life

Despite its reputation in the interwar years as an institution best fitted for sporting figures and “conventional” types, Hong Kong University nevertheless accommodated a wide variety of academic eccentrics.

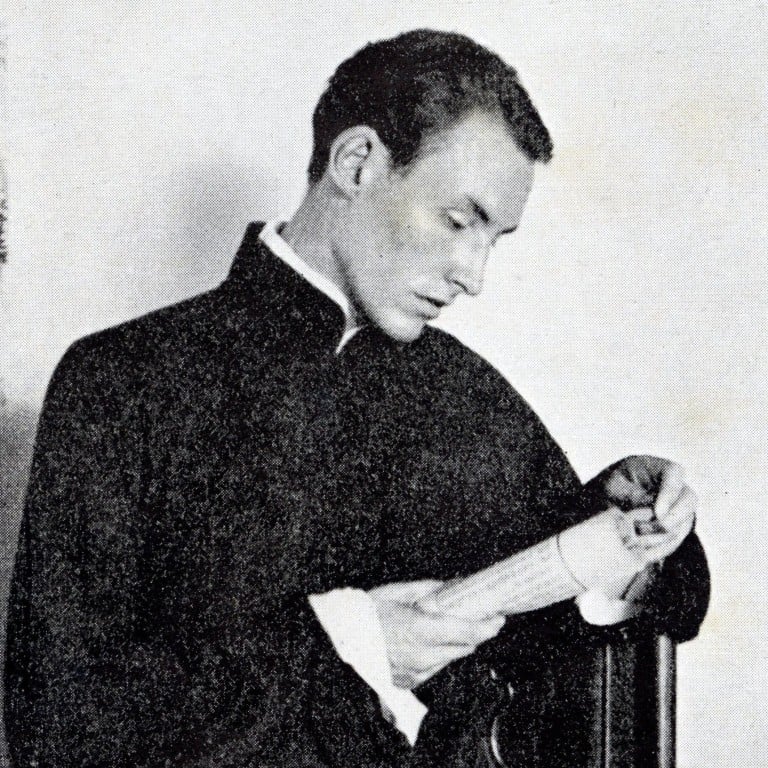

Some of these individuals were fondly remembered by their students for the remainder of their lives; one notable figure was Adrian Paterson, who taught in the English department from 1935 to 1938.

In a later memoir, Joyce Symons, afterwards headmistress of Kowloon’s elite Diocesan Girls’ School, recalled that “Adrian Paterson was everyone’s idol.”

With an unintendedly ironic choice of phrase, she continued that “in the closeted world of the thirties, the few women undergraduates found it exciting to be taught by youngish men, instead of the more elderly women we had encountered hitherto.”

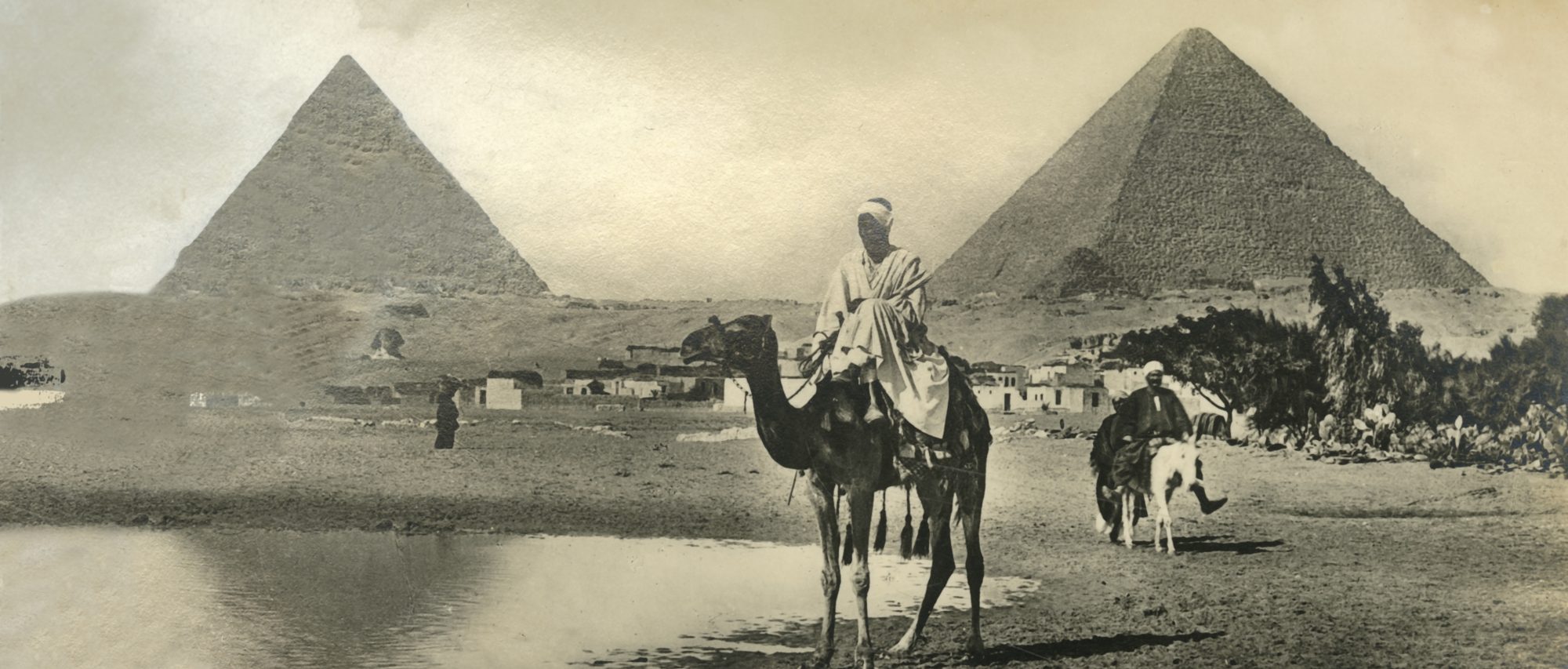

Born in England in 1909, educated at Oxford University, where he was a student and friend of scholar and theologian C.S. Lewis, Paterson graduated with “a very good Second”. He taught in Lithuania, then was appointed to a post in Cairo, which he was unable to take up so instead he came to Hong Kong.

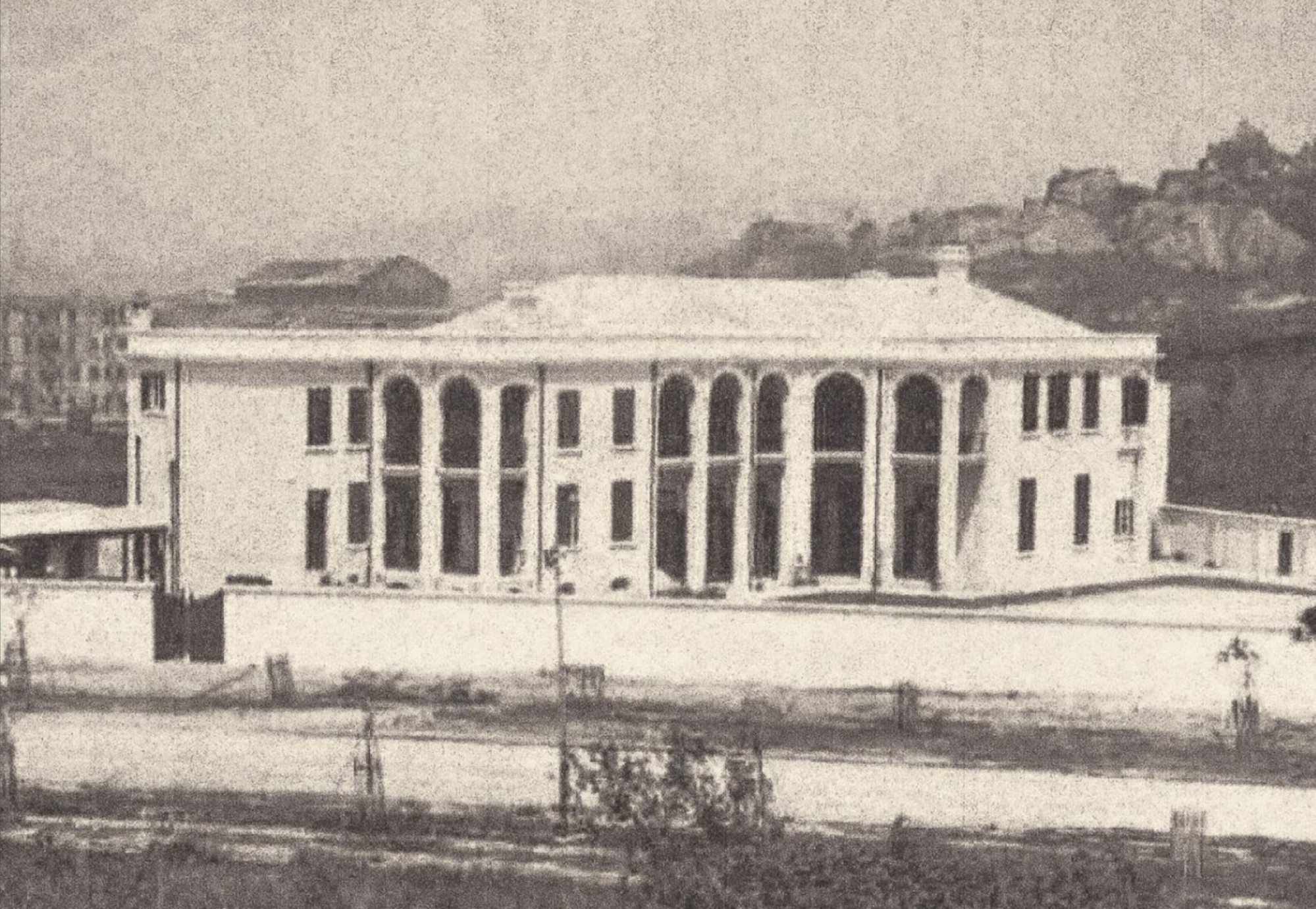

Paterson was warden of Hong Kong University’s May Hall from 1936 until his departure, and also involved in theatrical performances.

Chung Heung-sung, later an eminent scientist, described taking part in a production of Macbeth, which Paterson produced and directed.

“A remarkably energetic and resourceful young Englishman, he made full use of whatever talent he could scrape up from the limited pool available to him, since few of the students had any previous acting experience.”

There were other benefits, because “through the rehearsals and other activities associated with the production, I was able to widen my circle of friends and greatly enrich my social and cultural life at the University”.

Why Chinese around the world love fermented bean curd – even stinky tofu

Paterson studied Chinese in order to read philosopher Lao Tzu, and enjoyed Tang poetry in the original form.

One anonymous HKU contemporary noted, in a memoriam article published after Paterson’s untimely death, that “although most Europeans here admire the Chinese civilisation and culture, few dare to look the Chinese gentleman to the last detail.

“Some go so far as wearing a Chinese gown at home, but only at home. However, this English lecturer sometimes wandered about in the University compound in his blue Chinese gown, putting to shame many a student who had discarded his ancestral robes for something only slightly better than pyjamas.

“Anybody who has known him for some time must admit that he was neither crazy about old civilisations nor pretended to admire them, just to be different from others.

“His peculiar studies, ideas, conversation and behaviour were all so unconventional solely because he was seeking for the truth, and dared to do and talk about what he had learned to be true. Or, if he was not a little bit cracked, was he just another of those China-admirers from the West? [Always] he asked for green tea, served in a Chinese cup, which he held in the proper Chinese way.”

The same writer shrewdly continued, “Or – was he just that kind of person who loves any civilisation, except his own?”

On a slow boat to China: when ships connected Southeast Asia and Hong Kong

This analysis was probably the closest; a spiritual seeker, Paterson first explored Buddhism, then Catholicism, then converted to Islam when he moved to Cairo to teach after his HKU contract ended. But he didn’t have much time to discover whether Islam was finally right for him.