Shanghai in the 1930s brought to life through enchanting conversations with Billie Gill, a former fixture of the Chinese city’s literary scene

- Louise Mary ‘Billie’ Gill was at the centre of Shanghai’s literary scene in the ’30s and went on to work for the UN. We met her before her death in 2006

- In conversations by Lake Geneva, she spoke of long-ago places and people accompanied by her son, who recently released a memoir about her fascinating life

Fascinating characters first encountered in the pages of long-ago books seldom enter one’s own life as flesh-and-blood personalities. One who did was Louise Mary Gill, née Newman – better known as Billie.

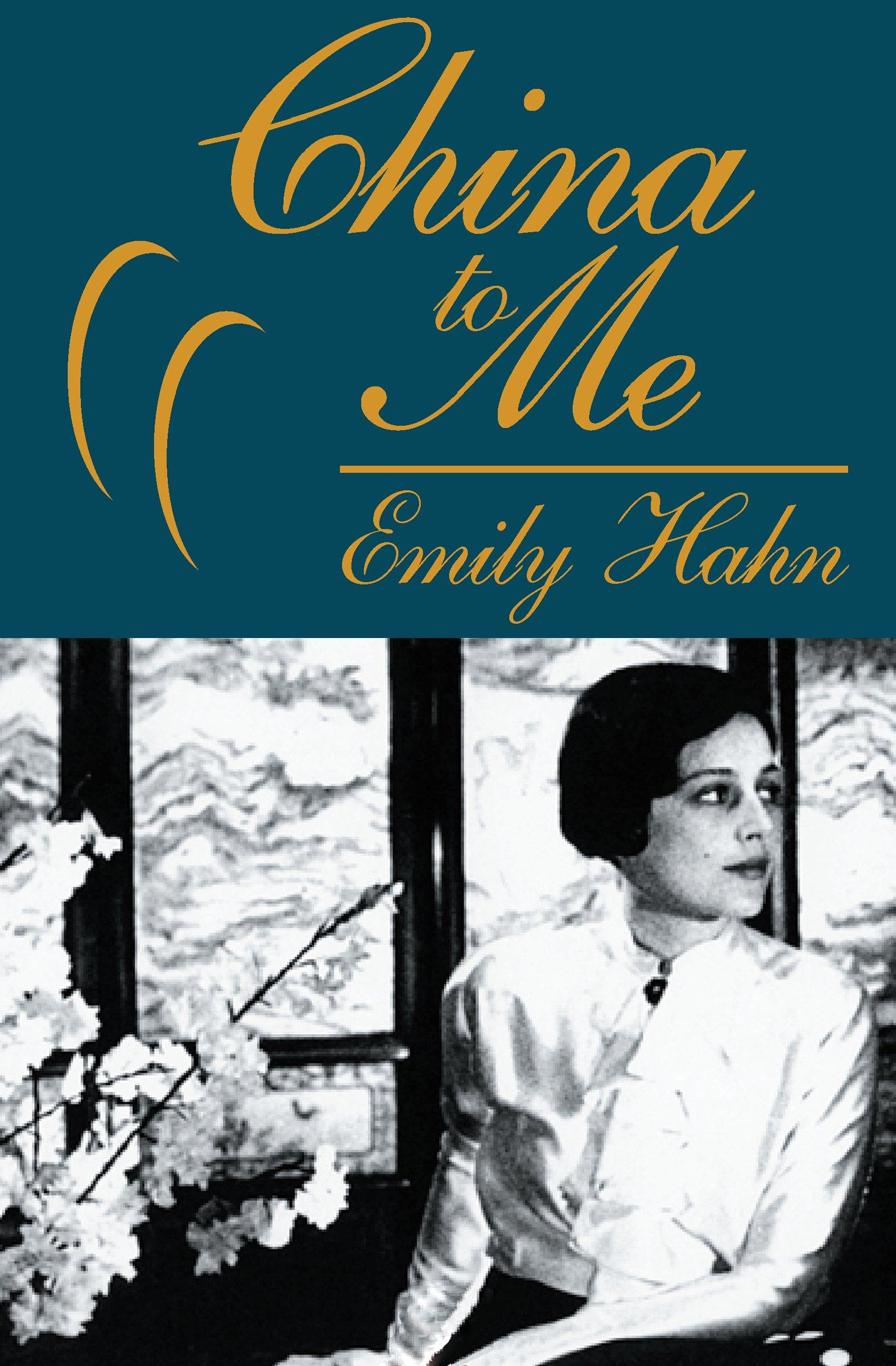

My first introduction came from China To Me (1944), American writer Emily “Mickey” Hahn’s rollicking memoir of life in Shanghai, Hong Kong and wartime Chungking.

In this vividly realised account, she was known as Billie Lee. Depicted perhaps a little too candidly – much as Hahn wrote about practically everyone she encountered – they nevertheless remained lifelong chums. When we met in England in 1996, Hahn spoke warmly of her old friend and said, “You’ll like Billie – most people do!” And she was right.

Fascinating conversations ensued; two particular memories stand out – a long drive followed by a delicious lunch at Montreux, looking back towards the Alps and Vevey beyond; Charlie Chaplin had lived up there for many years.

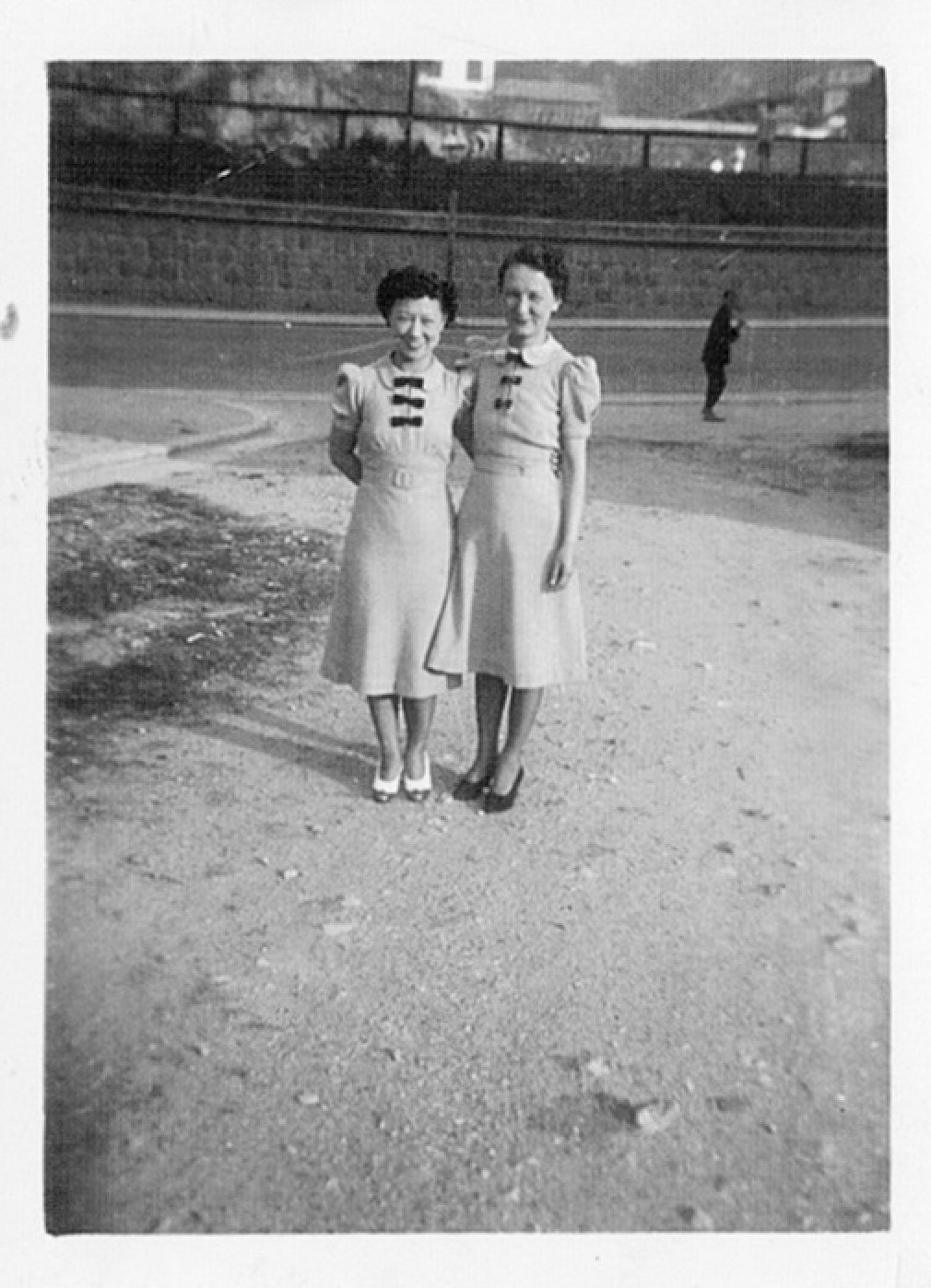

Talk turned to long-ago times and places, in particular 1930s Shanghai, and the extraordinary, fascinating literary coterie Billie encountered through her work at T’ien Hsia Monthly magazine.

As a teenager in Australia’s Queensland, through Auntie Lorna, a book-loving, hard-core socialist friend of my grandmother, I first encountered Lin Yutang, the renowned Chinese philosopher-humorist.

Never would I have imagined – then – that two decades later, at a restaurant table in Switzerland, I should spend hours with an enchanting old lady who had not only been a friend of Lin, but had typed successive manuscript drafts of that very book.

“Do you miss Shanghai,” I asked, as we looked out over Lake Geneva. Billie’s direct, no-nonsense answer was illustrative of much more than just the obvious reply. “Not at all, no,” she briskly remarked. “Because you see, Shanghai no longer exists – at least, not as I knew it then. So, there’s nothing to miss.”

From that encounter with someone who – nearing the further end of life’s arc – had a great deal to recollect, one learned that remembering and looking back represent clearly separate and distinct states of mind.

Another was a memorable lunch at Geneva’s Palais des Nations, where Billie had worked for years during her career with the United Nations. Arrayed on the dessert table were the most delicious-looking ilês flottantes ever seen – “Have another one, go on!”, Billie urged, with an indulgent smile; who could refuse?

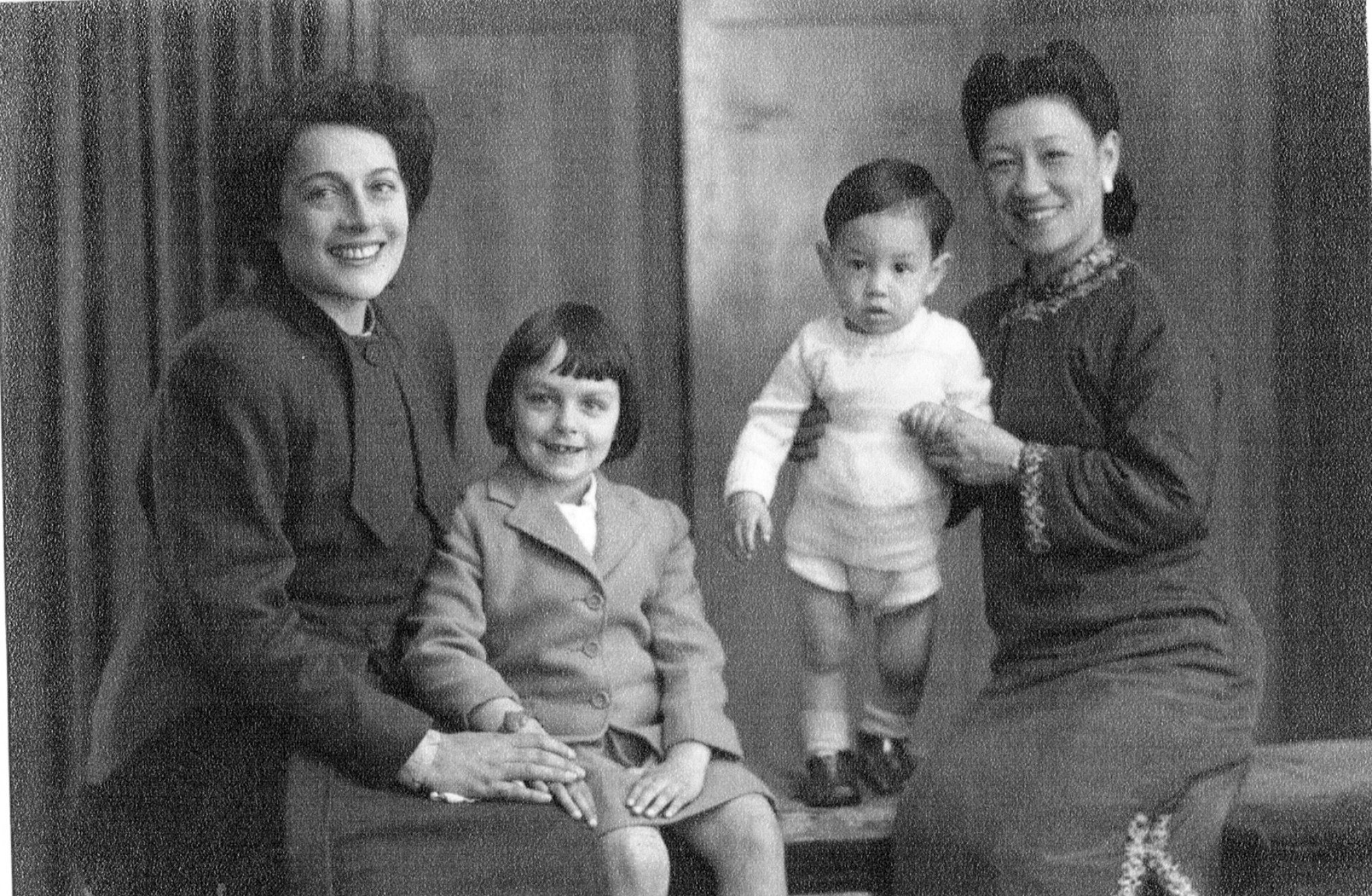

Other long-ago China personalities came alive on that occasion; in particular, the legendary Soong sisters, of whom it was said – and Billie herself repeated the famous line – that one loved money, one loved power and one loved her country.

Despite the fact that The Soong Sisters (1941), Hahn’s biography of the trio, was an authorised version, “Madamissimo” apparently entertained second thoughts thereafter about anyone too closely associated with its colourful author.

That encounter in Switzerland was the only time we met. News of Billie periodically arrived via Ian, and I was saddened when she died in 2006. But now and again, pleasant memories of those brief-yet-memorable days – and the long-vanished people and places we spoke of – come smiling back in quiet moments.

As part of the Hong Kong International Literary Festival, Ian Gill will be at the Fringe Club, in Central, talking about his book, Searching for Billie, on March 9 (1pm-2pm) and taking part in an event called “In Conversation: Historical Hong Kong – Vaudine England (Fortunes Bazaar) & Ian Gill (Searching for Billie)” on March 10 (11.30am).