Jailed for plotting to kill Mao Zedong, eclectic publisher, first director of Hong Kong University Press: meet Henri Vetch

- After World War II, Frenchman Henri Vetch built a publishing career in China before being implicated in a bizarre plot to assassinate Chinese leader Mao Zedong

- In 1954, he was appointed as the first director of the Hong Kong University Press, and later established Vetch and Lee, which produced a range of unusual books

One name that regularly recurs in memoirs of foreign life in China between the world wars is that of Frenchman Henri Vetch.

Warmly remembered as “a tremendous talker with enormous energy”, this perennially colourful figure of Peking’s interwar European life for almost three decades first went to China in 1920, after serving as an officer in the French Army during the first world war.

According to his close friend and Hong Kong University colleague Geoffrey Bonsall, Vetch once confided to him that “he was unable to decide what else to do” after the war ended, and so decided to join his father, who was already established in the publishing business in Peking, as this choice offered him “as reasonable a career option as any other”.

First with his father, and then independently, Vetch operated the Librarie Française, an independent booksellers and publishing house in the internationally famed Grand Hôtel de Pékin.

The Hong Kong University teacher that was ‘everyone’s idol’ in the 30s

For almost three decades, he produced attractive works on a wide variety of subjects. As a publisher, Vetch’s list was eclectic, though, unsurprisingly, China-related themes predominated; Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking (1936) is a representative example.

Other than a few visits to Europe, Vetch lived in mainland China and later, in Hong Kong, until his death, in 1978, aged 80.

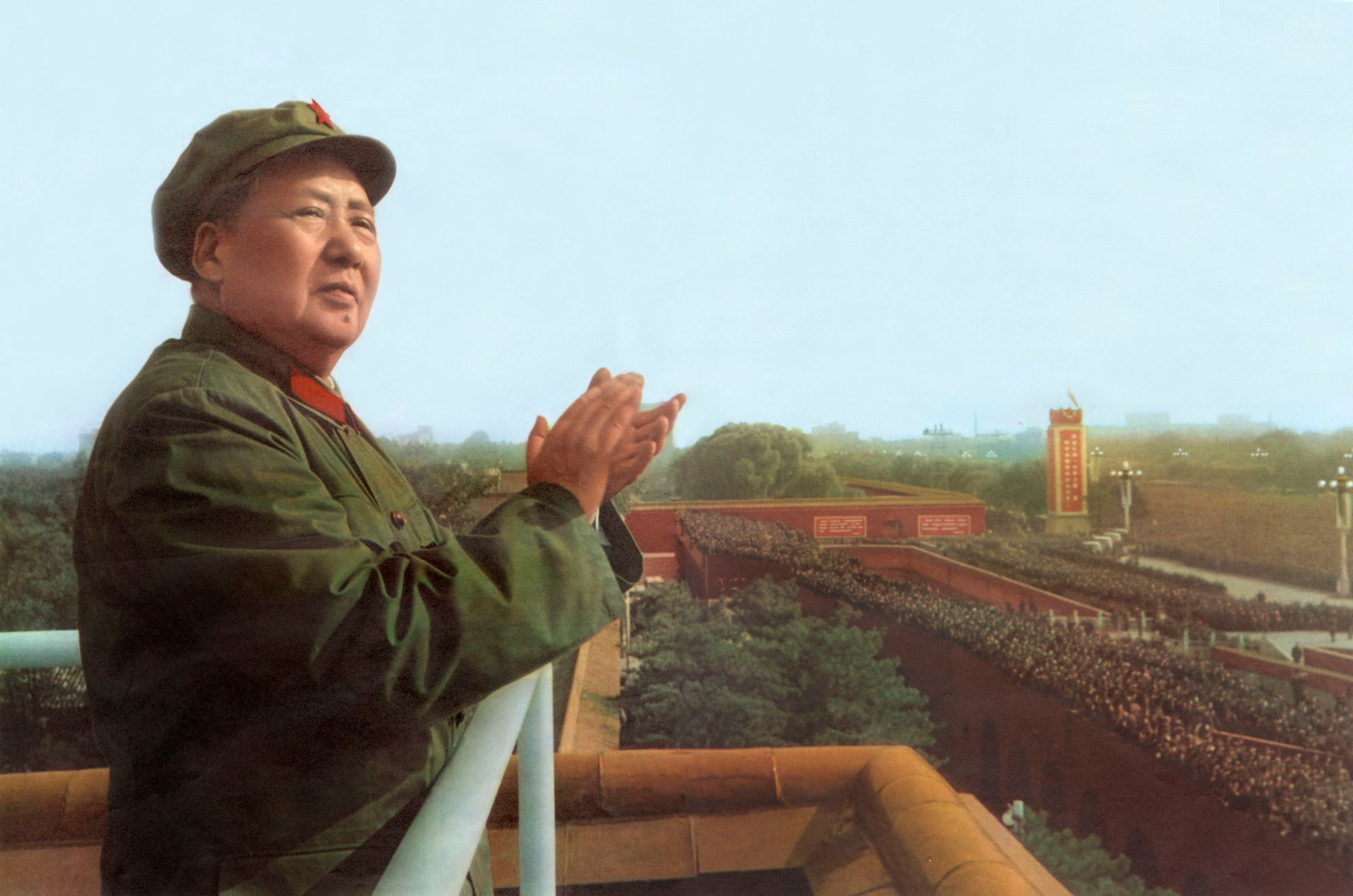

In the immediate aftermath of the Communist assumption of power, in 1949, Vetch was implicated in a bizarre plot to assassinate Mao Zedong.

Exact details of what happened (or did not) remain sketchy; a vivid account recalled at a public lecture in 1977 by Vetch himself varied significantly from both official and newspaper accounts from that time. But whatever the truth, Vetch was released and finally deported to Hong Kong in 1954.

Time spent in a Chinese prison was not wasted; the experience finally allowed him to perfect his Mandarin – a long-held ambition.

Soon after his arrival in the British colony, almost penniless and without any material vestiges of his earlier life in north China, Vetch resumed his life as a publisher, but under significantly different circumstances.

A brief but beautiful encounter with a key literary figure from 1930s China

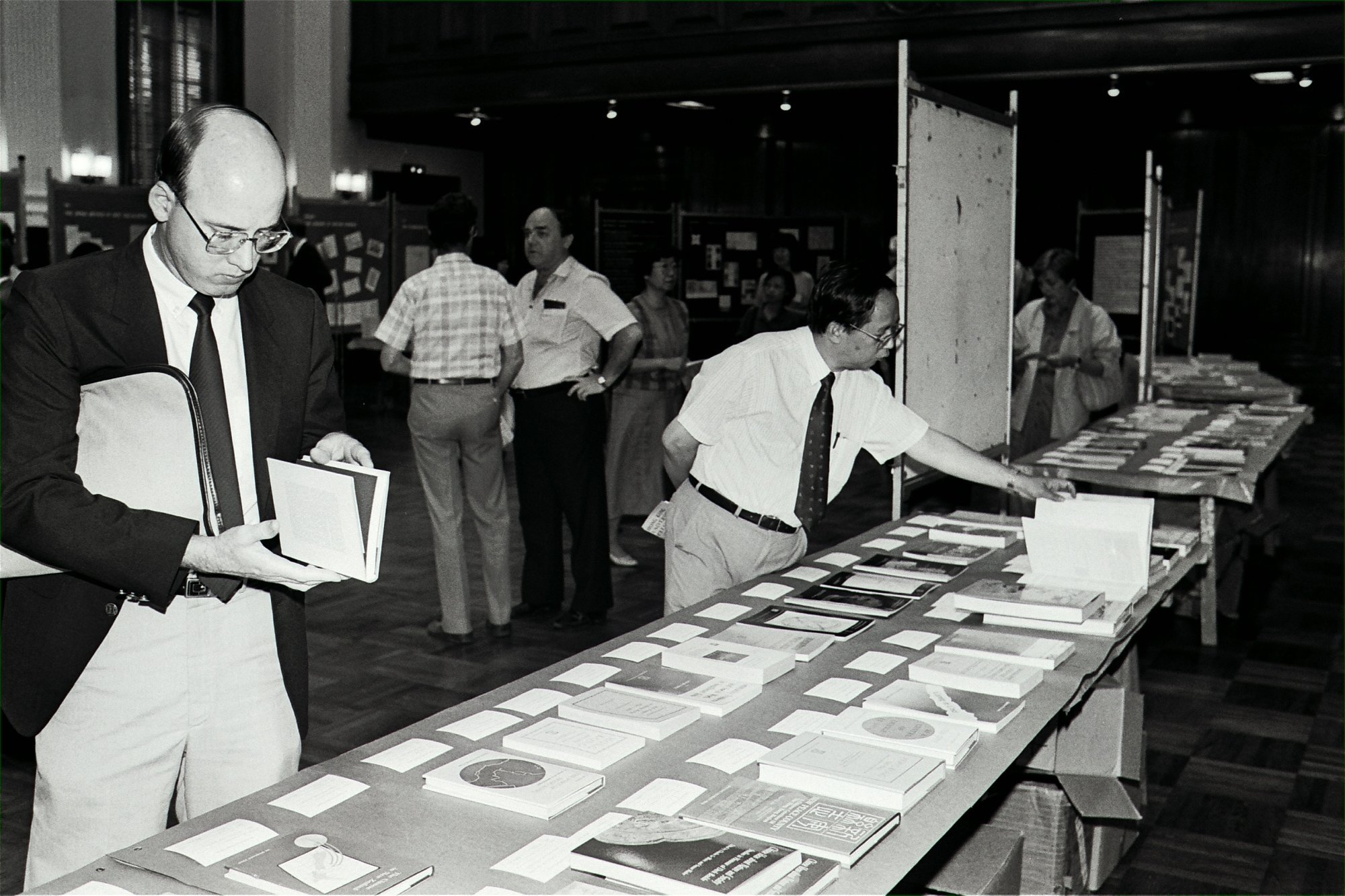

Due largely to the intervention of Sir Lindsay Ride, then the vice-chancellor of Hong Kong University, in 1954, Vetch was appointed as the first director of the newly established Hong Kong University Press – as the publisher was at that time known.

Vetch remained in that role until 1968 – well past normal academic retirement age – and, to nobody’s surprise, produced numerous worthwhile titles on a wide array of subjects.

When he left Hong Kong University Press, Vetch established Vetch and Lee, his own independent outfit, which produced a variety of interesting and unusual books.

Among the most significant was a reissue of James William Norton-Kyshe’s monumental two-volume The History of the Laws and Courts of Hong Kong from the Earliest Period to 1898 (1971).

Except for Vetch’s timely reprint, this essential reference source for 19th century Hong Kong – the sheer scope of this magisterial work extends far beyond a record of judicial proceedings – would otherwise be almost unobtainable by present-day readers.

Other quirky reprints produced by Vetch and Lee, such as Guido A. Vitale’s Chinese Folklore: Pekinese Rhymes (1972), are still periodically available locally as new copies; when the firm went out of business in the early 1970s, remaining stock was acquired and is still available for sale.

Despite being a lifelong devout Catholic, when Vetch died he was sent off in a Chinese coffin from the Buddhist ceremonial hall at the crematorium, much to the confusion of some who attended his funeral. His ashes were subsequently buried in a family crypt in France.