The dream weavers of Sarawak, headhunters once, fight to save their art and their traditional way of life

Inside the disappearing world of Sarawak’s Iban tribal weavers, who literally dream up the intricate patterns of their pua kumbu, beautiful ceremonial cloths with a bloody past

It’s dawn and Bangie anak Embol has been up for an hour or so, washing clothes, reciting prayers and chatting with neighbours in Rumah Gareh, an Iban longhouse in central Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo.

In the day’s first rays, the septuagenarian heads for the well-tended garden in front of the longhouse, knife in hand, ready to cut a few stems of tarum, the indigo plant she’ll use to dye cotton yarn for the pua kumbu ceremonial cloth she is weaving.

Mixed with hot water, lime juice and a spoonful of ground snail shells, to help fix the dye, the threads quickly acquire the green of the indigo plant before gradually turning blue. The longer the soaking, the deeper the shade.

We are guests at the longhouse thanks to Welyne Jeffrey Jehom, professor of anthropology at the University of Malaya, in Kuala Lumpur. Jehom has been researching Sarawak’s weaving traditions for years, and since 2012 has focused on pua kumbu, the ceremonial cloth woven by Iban women. Jehom has initiated conservation and commercial projects aimed at preserving the pua kumbu tradition and now visits Bangie and her fellow weavers on a regular basis.

Getting to Rumah Gareh – or “Gareh’s longhouse”; Gareh being the current headman, Bangie’s son – is no mean feat. An express boat takes us from Sibu, a nondescript town near the Rajang River’s swampy delta, to bustling Kapit, where connections can be arranged to all the longhouses – villages under one roof that are typical of Borneo’s indigenous communities – on the upper Rajang and its tributaries.

Hoping to sit with locals on the boat’s low roof, we are gently rebuked by a Sarawak Rivers Board official; boats often bump into logs floating unseen downriver, he explains, and people have been thrown overboard and drowned in the swirling waters. We are, after all, in logging country, and these long, powerful, bullet-shaped boats are nicknamed “floating coffins”.

Grateful for the advice, we move into the damp, chilled cabin, occasionally venturing onto the 45cm-wide deck, holding tight to the handrails. And still we manage to get sunburned.

Having arrived in the evening, we spend the night in Kapit.

Investment is quickly changing what was a lonely garrison outpost during the era of the White Rajahs, the dynastic monarchy of the English Brooke family, who ruled Sarawak from 1841 to 1946; Fort Sylvia, named after Rajah Charles Vyner Brooke’s wife, is the last vestige in Kapit of those times.

Next morning, we peruse the fresh produce for sale by the roadside before lining up for another express boat. For two hours, we head up the Balleh River towards Nanga Kain, a hamlet of small houses, one general store and a primary school (boasting the only landline telephone for miles around), which gives its name to the administrative division of which Rumah Gareh is part. From here, the longhouse is a 40-minute, tree-shaded ride by long-tailed boat along the shallow Kain River.

Remote and surrounded by majestic riverine rainforest, Rumah Gareh has been the nucleus of the pua kumbu tradition for decades, receiving visitors from near and far. It remains the only Iban longhouse that meticulously adheres to the traditional process of pua kumbu weaving and where shamanic rituals are sometimes still conducted.

According to custom, the women are in charge of producing the cloth that helps keep the Iban close to their gods. Their dreams play an important rolein determining the patterns, offering a glimpse into the weaver’s soul.

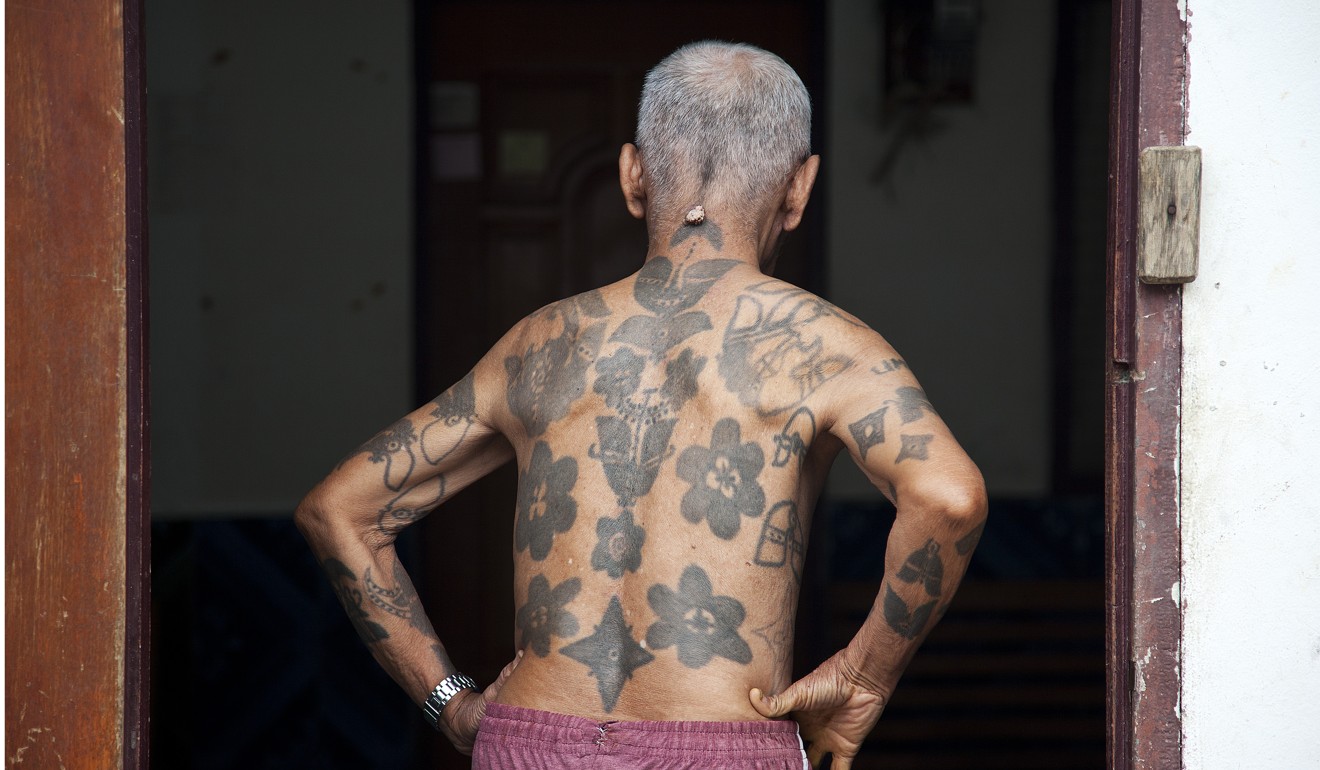

Iban men were once headhunters, and the two rituals were interconnected. The cloth would be used to goad the men to venture out and prove their mettle; on their return, the women would cradle in pua kumbu the heads they had brought back, dancing and coaxing out the spirits residing in the skulls. Those spirits would then be entreated to bless the longhouse community.

Nearly a third of Sarawak’s population are Iban, a people who started migrating northward from Kalimantan, in Indonesian Borneo, in the 1600s in search of arable land. Their encounters with native groups were far from peaceful.

The White Rajahs put an end to headhunting in Sarawak more than a century ago, but pua kumbu (“the Iban women’s warpath”) remains potent, and wooden back-strap looms, used to weave the cloth, can be seen in many longhouses along the Rajang and its tributaries.

Rumah Gareh’s ruai, the longhouse’s spacious communal gallery, seems filled with a deeper sense of collective responsibility than most. Here, Bangie and her disciples maintain a steady level of production and quality. Their efforts are promoted by individuals such as Jehom and Malaysian fashion designer Edric Ong, who first brought pua kumbu and weavers like Bangie to the world stage in the late 1980s, as well as conservationist bodies such as the Tun Jugah Foundation, in Kuching.

Younger Iban elsewhere along the Rajang have mostly lost interest in the old ways and moved out of their longhouses to find better-paying jobs in Kapit or Sibu. Many of the older womenattempt to earn a meagre income weaving simple pieces for the tourist market, using chemical dyes instead of less accessible natural ones.

“Rumah Gareh is unique in its attachment to authentic practices, like the use of natural ingredients,” explains Jehom. “Though the cotton or silk yarns are now mostly brought from outside, the mordant [a fixative made of wild ginger, nuts, seeds and other roots] and the dyes [indigo for blue, tree roots for red and the increasingly rare akar penawar landakvine for yellow] are still handpicked by the weavers.”

Over a vegetarian feast of jungle-grown produce, Jehom discusses the dilemmas faced by Iban weavers, who must choose between tradition and modernity, age-old rituals and commercial projects. Like Bangie, Jehom believes economic engagement is needed to keep cultural traditions alive.

Originally from Sarawak, though belonging to the Bidayuh group of peoples, Jehom taught herself the Iban language and has devised several initiatives to record pua kumbu practices and provide the weavers with a sustainable future. Among them is a training centre in Kapit, scheduled to open in September, where they’ll be able to pass on their skills.

“But the major challenge will be to find a knowledgeable, dedicated successor to Bangie,” acknowledges Jehom.

Though impressively sprightly for her 76 years, Bangie realises her time as a master weaver is drawing to an end. Who will take up the torch? Who will dream the dreams required to perform the rituals?

That night in Rumah Gareh, before the longhouse’s generator is turned off, no amount of tuak – a liquor made of fermented rice, yeast, water and sugar – is able to offer a solution.

Leaving Rumah Gareh behind, this time by four-wheel drive, it’s hard not to wonder what will happen to these weavers in what looks like a race against time. We travel on winding mud tracks carved by logging companies, pastvast areas of shaved, almost lunar landscape, where primary rainforest once thrived.

Extreme logging is one of the dark realities of Sarawak. It affects the longhouse communities deeply , forcing them off their ancestral lands so these, too, can be stripped and, later, exploited as palm-oil plantations.

Before wishing us “selamat jalai” (Iban for “bon voyage”), Jehom warns us that the threads of destiny might not be only in the weavers’ hands, but also in the loggers’ calloused fists. She and Bangie remain fiercely optimistic about the future, though, and place great faith in the power of pua kumbu.

Bangie anak Embol and her peers will appear at a pua kumbu exhibition, put together by Welyne Jeffrey Jehom, at the Rainforest Fringe Music Festival, in Kuching, from July 7 to 16

How to get there

Air Asia and Malaysia Airlines fly between Hong Kong and Kuching, and Sibu, via Kuala Lumpur