Pink Floyd in Pompeii: band’s 1971 Italian trip explored in exhibition

Psychedelic rockers’ performance at the preserved Roman city recalled in showcase of photos and memorabilia – and music

Bouncing off the ancient walls of Pompeii’s amphitheatre, Pink Floyd’s synthesised sonics are as much of a surprise to my fellow tourists as the first deep growl from Mount Vesuvius perhaps was to the city’s inhabitants some 1,900 years ago.

A fan on a bucket-list pilgrimage to the Unesco World Heritage Site, I was well aware of the “Pink Floyd Live at Pompeii Underground” exhibition here, and am pleased to discover the little-known showcase of the band’s iconic 1971 gig comes with audio.

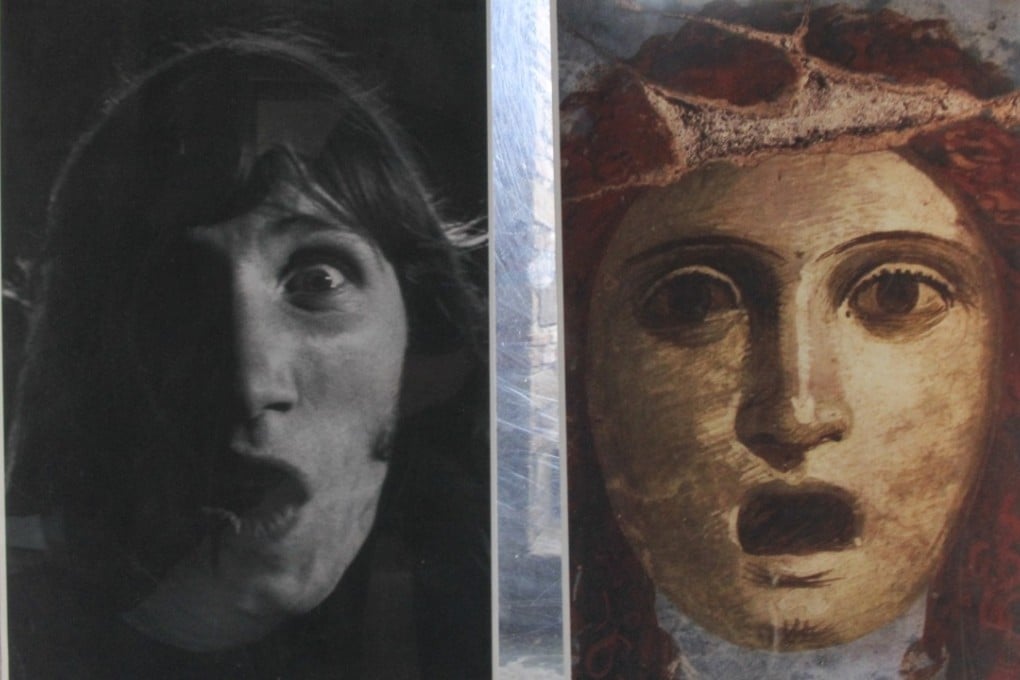

Along the passageways under the amphitheatre’s tiered seating are hung 250 never-before-seen photos and other memorabilia of the band performing in the empty stadium, observed only by the small film crew and French director Adrian Maben, who conceived “rock’s wackiest idea, ever” half a century ago, and who curated the current exhibit. Two large screens play the legendary concert documentary on a loop, and the soundtrack follows visitors along the stone tunnels from a series of speakers, the psychedelic melodies adding to the ethereal atmosphere.

The exhibition is not mentioned in the guidebooks and many of my fellow travellers wander in, unaware of what awaits. “Let’s get out of here,” exclaims a child of the noughties to her boyfriend as a version of Seamus, from the band’s seminal album Meddle (1971) and renamed Mademoiselle Nobs for Pompeii, strikes up. Keyboardist Richard Wright holds a microphone to the mouth of his Afghan hound, named Nobs, which duly howls like a tortured banshee at David Gilmour’s harmonica playing; there’s no denying some early Pink Floyd numbers are not for the faint-hearted or appreciated by those prone to tinnitus.