Finding the Mona Lisa’s background on a road trip into the heart of Italian culture

Heading inland from Rimini on the Adriatic coastline, La Marecchiese is a showcase of Italian flair and fare nestled in the Emilia-Romagna region, recently voted the Best Destination in Europe by Lonely Planet

“Even if I set out to make a film about a fillet of sole, it would be about me,” Federico Fellini once said. The Academy Award-winning director of La Dolce Vita (1960) and Amarcord (1973) devoted a great deal of his art to reviving memories from his childhood, which was spent in Rimini, an old Roman town in the southeastern part of Emilia-Romagna (the region has just been designated Best Destination in Europe 2018 by Lonely Planet), on Italy’s Adriatic coast.

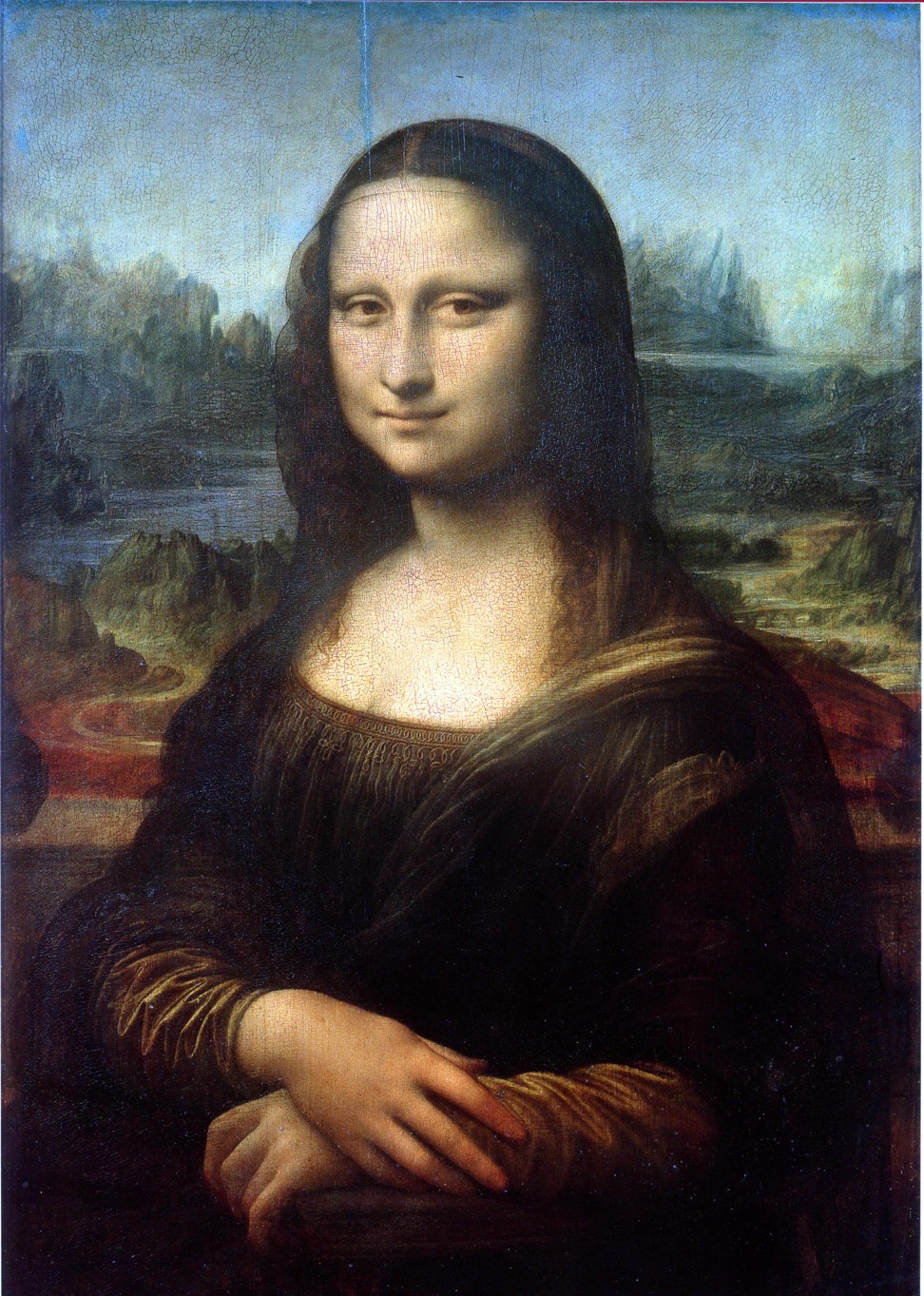

La Marecchiese, a 50km stretch of bitumen more formally known as the SP258, heads inland from Rimini and doubles as a concentrated thread of Italy’s very essence: its art and culture; its food and wine; its landscape and poetry. We’re embarking on a two-day trip along La Marecchiese – with a detour or two – through ancient villages in which steep alleyways lead to castles perched on rocky hills that look down into the verdant Valmarecchia and Montefeltro valleys: a landscape so affecting, a recent study has found, Leonardo da Vinci used it as the backdrop to his most famous masterpiece.

A couple of steps from the Fulgor is Piazza Ferrari, where, in 1989, gas company workers stumbled over the Surgeon’s House (Domus del Chirurgo), a well preserved second-century AD Roman villa, complete with beautiful mosaics and the most extensive collection of medical tools from the era discovered to date. Scrawled on a wall, archaeologists found the inscription “Eutyches homo bonus”, a patient’s review of the resident doctor’s work. Eutyches was, reportedly, a good operator.

As the afternoon fades into evening, the young and the fashionable flock to the waterfront, prepared for a long night, but we skip the clubbing and head inland, to Santarcangelo di Romagna.

The hike up to the rocca has built up an appetite that only Ristorante Zaghini and its signature fresh tagliatelle with beef ragu can satisfy. The fireplace opposite the restaurant’s main entrance is a reminder that snow often falls over the hills of Valmarecchia and Montefeltro in winter.

The following morning, we head south, past 18th-century villas that hide expansive private gardens and ancient trees, before crossing a bridge over the rocky bed of the Marecchia. As the road rises towards Verucchio, the green landscape is interrupted only by small, distant villages.

First settled as long as 3,000 years ago, Verucchio witnessed the sunset of the Etruscan civilisation (the artefacts the village’s Archeological Museum houses include amber and bronze ornaments, clay pots, helmets and daggers, fabrics and, most impressive of all, a wooden throne decorated with human figures) before blossoming again during the Roman Empire and then gleaming with Renaissance splendour thanks to the Malatesta dynasty.

We take a detour from La Marecchiese to see another imposing edifice. In Montebello Castle, Azzurrina, the daughter of a 14th-century feudal lord, was kept hidden because she was an albino. Being born with white hair and clear glass-blue eyes was considered a mark of the devil and the girl’s mother dyed her hair with a pigment that, instead of turning them black, as intended, turned her locks light blue (azzurro, in Italian). In 1375, on June 21 – the summer solstice – Azzurrina disappeared while playing with a ball in the basement of the castle. She was never seen again but legend has it that every summer solstice, Azzurrina’s voice can be heard, a story that attracts ghost hunters from all around the world.

Glad it’s not June 21, we leave Montebello and proceed south.

Our final destination, Pennabilli, is gathered on top of the hills where Valmarecchia blends into Montefeltro, where Emilia-Romagna becomes sandwiched by Tuscany and the Marche region. The village is renowned for its festivals and fairs, examples being Artisti in Piazza (dedicated to street artists) and Mostra Mercato dell’Antiquariato, an antiques market that in summer attracts sellers and buyers in their droves. It was also Guerra’s final home, the poet having envisioned grand designs for Pennabilli before he passed away, in 2012.

“Do you know La Gioconda,” asks Giannini, squinting into the distance. It’s easy to understand why da Vinci painted the landscape of Montefeltro we’re now gazing at behind the Mona Lisa: this mellow, touching panorama perfectly complements the mystery and the subtle beauty of the quintessential Italian Renaissance icon.