- A journey from Hanoi, the Vietnamese capital, via former capitals Ninh Binh and Hue, to Ho Chi Minh City, its investment capital, reveals much about the country

It’s difficult not to think about trains while in downtown Hanoi, especially at mealtimes.

Long metal caravans shunting through town in plain view of the near-ubiquitous streetside eateries contribute a periodic clappity-clap rhythm to the city’s clamorous soundtrack.

Tracks girdle the historical heart of the Vietnamese capital like the head of a question mark and in doing so, connect two of Hanoi’s most popular sites: the Long Bien Bridge, a colonial structure spanning the Red River that was bombed so many times during the Vietnam war it became a symbol of national resistance, and Ngo 224 Le Duan (better known as Train Street), an alleyway along which trains pass perilously close to houses and makeshift cafes.

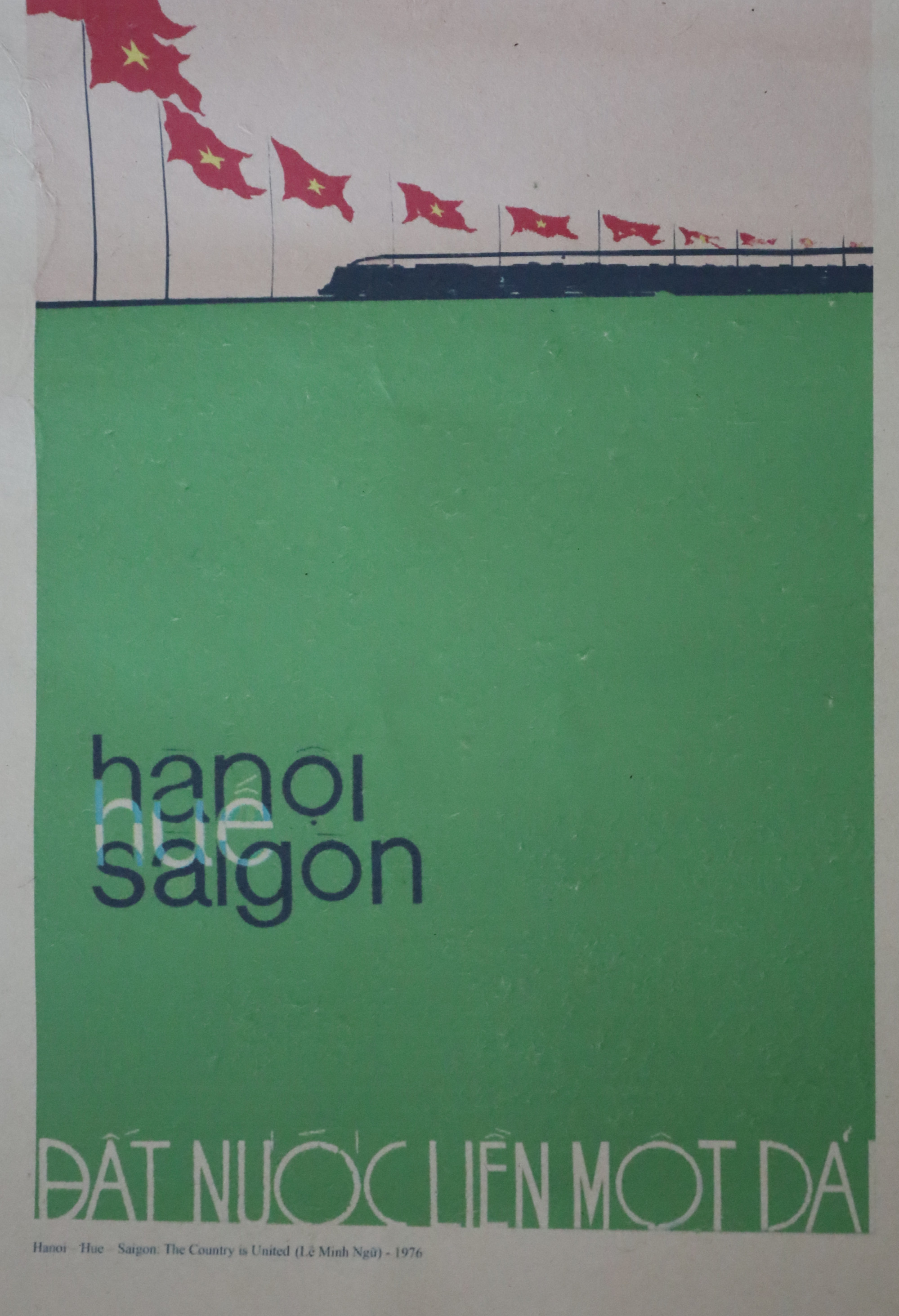

However, my travel inspiration comes not from the recurrent glimpses of locomotives, but from an old propaganda poster hanging in a tourist shop opposite the Cathedrale Saint-Joseph de Hanoi.

The print exhibits the simple aesthetics used to communicate a political idea, in this case, a train speeding past red flags above text that reads: “Hanoi-Hue-Saigon, the country is united on Line One.”

I decide to follow that route, from the northern political capital to the economic capital in the south, via the Nguyen dynasty (1802-1883) capital Hue, but am advised by a Vietnamese friend to include another, older capital, in Ninh Binh, where “the scenery is spectacular”.

Plan in place, I grab a hearty breakfast baguette, or banh mi, before departing Hanoi aboard the Reunification Express.

The name is given to all public trains (several a day) that run on the north-south railway, which was built by the French in stages from 1899 to 1936 to link “the backbone” of their empire in Indochina. During the wars that engulfed Vietnam through much of the 20th century, this vital transport corridor was often a target of sabotage and bombardment.

After the Fall of Saigon, on April 30, 1975, when the last American troops left the country, the victorious communist government took control of the war-ravaged railway, prioritising its reconstruction to get the economy back on track.

Eighteen months later, on December 31, 1976, trains were again rolling between the Red River and Mekong delta. The railway was duly promoted as a symbol of unity after decades of conflict.

Little beyond the carriage window recalls the warfare as the train leaves Hanoi. The crooked rows of shophouses that comprise the capital’s suburbs slowly give way to the spectacle that is Vietnamese karst country.

Alighting at Ninh Binh Station, 95km due south from Hanoi, two hours later at lunchtime – hardly a high-speed journey – it’s not long before I’m whizzing between limestone peaks and jade-coloured rivers on a rented scooter. Temples, pagodas and hilltop shrines dot the landscape.

From a tourist sign at the made-to-look-old imperial gate to the Hoa Lu Ancient Capital I read about when this now obscure village sat at the heart of Vietnamese affairs, from AD968 to 1010.

Although fronted by a grubby strip of restaurants, the old capital encompasses scenic gardens, patriotic monuments and excavated palace ruins, as well as reconstructed temples dating back to the 17th century.

The moss-covered Temple of Dinh Tien Hoang sits in the shadow of a towering limestone pillar like an illustration in a children’s fantasy book. A tourist sign in flawed English explains that, after the death of King Ngo Quyen, the country collapsed into civil war.

The bloodshed lasted 25 years, until AD968, when Dinh Bo Linh defeated 12 fighting warlords and declared himself emperor, founding the Dinh dynasty and renaming the country Great Viet.

Centuries after Vietnam’s very own Game of Thrones played out in and around Ninh Binh, the temple is tranquil,, if you ignore the hiss of insect song. A water buffalo grazes in a field nearby, incense smoke carries from an altar; the roots of a banyan tree appear to be reclaiming an entire wall for mother nature.

Stepping through a stone gate adorned with Chinese characters, I come upon a complex composed of symmetrical halls lined up along a central axis. The dragon carvings atop the temple reinforce the idea that the architect was borrowed from Vietnam’s giant northern neighbour, China having dominated the area for a millennium before the Great Viet was founded.

This is a Chinese temple with a lemongrass twist.

With another banh mi packed in my bag, I leave Ninh Binh on the afternoon service for the next 580km leg of my journey south. I have a lower bunk but there’s only one other passenger in our cabin of six, and he’s sleeping with an eye mask on, missing the spectacular scenery the train winds its way through.

I pick up a translation of The Sorrow of War (1991), by Bao Ninh, a stream-of-consciousness masterwork about the war in Vietnam based, in part, on the author’s own experiences. It is a harrowing read.

Periodically, I look beyond the pages at the forest-coated highlands lining the horizon where the narrator’s private hell played out.

Night falls heavy and fast in the city of Vinh, an economic powerhouse that grew out of the ashes of war. Little of the old town survived the previous century and the view from the train is of identikit high-rise towers, reminding me of industrial boom towns in China.

I arrive in Hue at 3am, under a cloak of darkness, all but blind to the heritage that surrounds me.

Daylight illuminates everything. Although heavily bombed by the Americans, Hue has some serious architecture to show for its ex-capital status, a role it performed from 1802 to 1945.

The city’s star attraction is the Imperial enclosure, a citadel-within-a-citadel overlooking the northwest bank of the Perfume (Huong) River.

According to a brochure procured at the Meridian Gate, Emperor Gia Long had sought a more central capital from which to govern the expansive Vietnamese realm with its newly acquired southern territories, so he moved the imperial court from Hanoi to Hue in 1802.

He also took political inspiration from Vietnam’s old overlords, employing “Chinese models of statecraft” to govern. In keeping with his Sinicised world view, a palace complex based on Beijing’s Forbidden City was commissioned.

It’s a pretty faithful rendering of Ming majesty; I pass Mandarin villas and go through ornate gates into courtyards that front plush palaces weighted down by flaxen enamel tiles.

There are also ruins; rubble-coated wasteland in between Nguyen dynasty splendour, the empty spaces left as a reminder of the Battle of Hue, in 1968, during which much of the city was razed.

‘It has just exploded’: Thailand train blogger’s exciting journey

I hop on a dragon-fronted riverboat for a sunset cruise on the Perfume River. Along the riverbanks, Vietnamese tourists dressed in traditional silks are posing for photos at scenic locations.

I alight at a downstream jetty situated just before the city’s top selfie spot, the Thien Mu Temple. With bats circling it and the sky turning purple overhead, it is easy to see why some consider this 400-year-old, seven-storey pagoda the city’s most prominent landmark.

Navigating a path between knick-knack vendors and evening sightseers, I climb into the temple grounds to seek out a hidden treasure, a marble turtle bearing a stone stele adorned with the words of a Nguyen lord who ruled southern Vietnam during the 17th century.

“An emperor wrote that,” a passer-by tells me while I try to figure out the script. “But we can’t read it,” he adds, alluding to the fact that most Vietnamese cannot read much Chinese nowadays.

The Latinisation of the Vietnamese language was initiated by early Portuguese missionaries but was popularised during the colonial period.

An alphabet is not the only thing the Europeans left behind. Hue Railway Station is a superb period building, wine-coloured and topped with a clock tower. Dating back to 1902, it survived the Battle of Hue unscathed and is now considered one of the best preserved examples of colonial-era architecture anywhere in Vietnam.

Back on board, I swing my bag onto my bunk for the overnight run to the southern terminus. I perch by a window on one of the stools left in the corridors for travellers to use, and read up on Vietnamese history over an iced coffee.

The travel gods have kept the journey’s highlight for the final leg. Between Hue and Da Nang, the mountains that dominate the Vietnamese interior cascade towards the coast, a fold in the landscape that causes the railway line to snake its way into green hills above the blue sea waters.

Our speed slows as we negotiate a steep incline and sharp turns, giving an avid watcher plenty of time to absorb the splendour of it all.

The train makes its final run into the sprawling suburbs of Ho Chi Minh City at sunrise the following day. I awake to find the man in the bunk below has brought a cat along for the ride.

“I’m from Saigon,” he says, reminding me that nobody in the South uses the new name, imposed to “honour Uncle Ho’s sacrifice and leadership” after South Vietnam’s defeat. Even the station is still called Saigon Railway Station.

With the city having been the capital of French Indochina from 1887 to 1902, and again from 1945 until 1954, arriving tourists are inevitably drawn to buildings such as the Opera House and Hotel Continental, which exude fin de siècle charm.

But it is as the capital of international investment that Ho Chi Minh City derives its most striking quality today, manifest in towering glass and steel structures that make the old buildings look like children’s toys by comparison.

Air-conditioned coffee houses dot the city centre, but I’m able to find a roadside stall from which to grab a banh mi, a culinary book end to my railway odyssey.

It’s been four days since I set out, and I’ve traversed not just 1,726km but 1,000 years of Vietnam aboard the Reunification Express.