Smithsonian’s Burning Man art exhibition invites an open mind

In the low-lit, second-floor room of Washington’s Renwick Gallery, a cluster of three ceiling-height plastic mushrooms glows in a shifting kaleidoscope of neon colours. At each mushroom’s base is a pad that users can press, causing the sculptures to heave, sigh, and expand in and out.

The installation, Shrumen Lumen by the FoldHaus Art Collective, was initially on view under the night sky at Burning Man, a week-long annual festival in the Nevada desert that celebrates the various joys of communal living, 24-hour dance parties, public art, provocative costumes, substance use, and a potpourri of spiritualities.

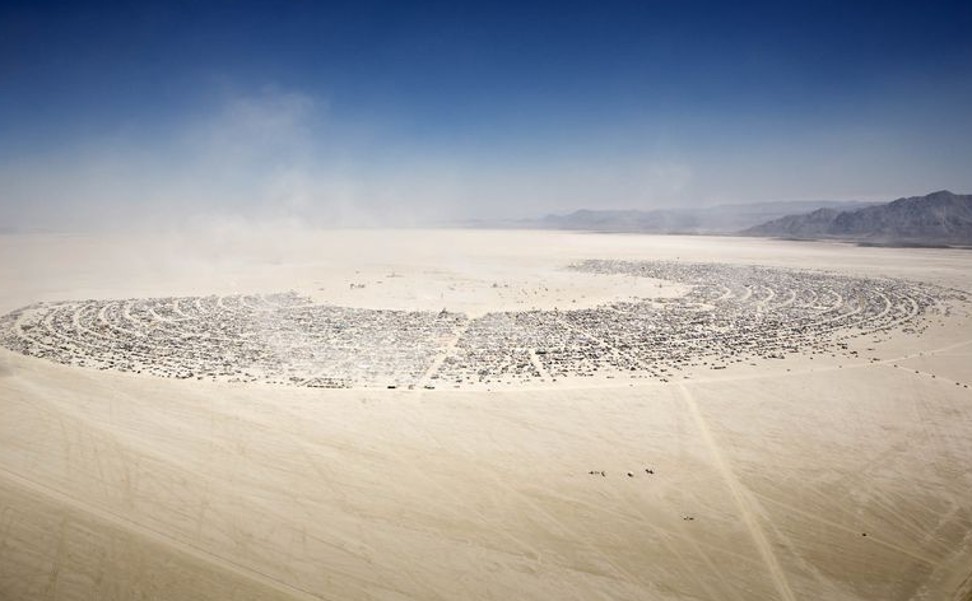

The event, wherein a 70,000-person temporary city is erected in a week and disassembled faster, is so singular that attempts to recreate it at other times of the year have fallen flat.

This is why organisers of the exhibition “No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man” (March 30 to January 21, 2019) faced a steep challenge when trying to transfer pieces of art from the desert to a museum context, specifically to the Renwick Gallery branch of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington. What proves to be the show’s saving grace is that it doesn’t try to be about Burning Man; it aims simply to evoke what it’s like to interact with the festival’s art.

“We’re in an 1860s building in the centre of Washington, D.C., and it transforms these pieces,” says Nora Atkinson, the show’s curator. “I’m not trying to recreate the desert, but I do want people to really get a sense of what [being there] means, because that’s what the work was created for.”

I went to Burning Man once, in 2006. I didn’t really plan for it, and I’m not sure I could have. The location (a sun-baked expanse of white sand roughly two miles across), the expanse of the crescent camp-city, and the endless stream of activities and parties that run until dawn and beyond were so fantastical that it beggared belief.

Aside from the immense cost required to attend the festival (easily, thousands of US dollars), what struck me most were the sculptures littered across the desert. The distances at Burning Man are so vast, and the desert (or “playa,” in Burner terms) is so empty, that objects which appear as dots on the horizon slowly reveal themselves to be massive, fanciful pieces of art as you approach. Often as not the art is interactive, or at the very least, something you can climb on or go inside, and the sense of discovery and playfulness can be genuinely thrilling. Much of it is burned before the end of the week.

The art at the festival is either commissioned by Burning Man, or donated, and every year there are contributions from dozens of artists. Over time, much of the sculpture has taken on some unified stylistic and structural components.

First, most of the art at Burning Man is big. There have been, for instance, seven-story-high wood statues of embracing human figures, a 26-foot-high flame-throwing metal octopus, and a full-scale replication of the shell of a gothic cathedral.

Second, the art almost always lit up. Much of the action at Burning Man takes place at night, and so the lighting, while admittedly dazzling, also helps people avoid running into sculptures by mistake.

Monumentality and light displays aren’t necessarily a great fit for any interior, anywhere, but Atkinson, who had free rein to select whichever Burning Man art she wanted, cannily decided to include works just big enough to seem huge. “I love that the mushrooms [Shrumen Lumen by Foldhaus Art Collective] look massive in our galleries, when they’d look tiny on the playa,” she says, referring to the dusty stretch on which the festival occurs.

The looming feeling of the artwork, and its interactivity, makes it fun. One room, for instance, features a series of steel sculptures by Yelena Filipchuk and Serge Beaulieu, whose artistic practice is issued under the name Hybycozo. The sculptures are lit from the inside with LEDs and can alternately be climbed internally or spun to create psychedelic light patterns that splash around the walls.

Most of the art in the Renwick was originally installed at Burning Man, but a few objects, including an 18-foot-tall, stainless steel sculpture of a nude woman dancing (Truth is Beauty, by Marco Cochrane) are variations on larger – and, in many cases, since incinerated – sculptures that once existed on the playa.

On the upper level of the Renwick, which includes a small archive show that gives the history of Burning Man – this is a condensed version of the show “City of Dust: The Evolution of Burning Man,” organised by the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno – stands a colossal wooden temple designed by David Best and the Temple Crew.

“David Best was one of the reasons I wanted to do the show,” Atkinson says. “So the temple was really important.”

The site-specific temple fills three walls of a room that spans the width of the building and features a wildly intricate, chandelier-style centrepiece. The entire installation is made of wood; what makes it all particularly impressive are the layers of thousands of pieces that suggest paper cut-outs. While there’s a geometry to the space, each of its many alcoves is unique. Out in the desert, Best annually builds an elaborate temple at which people write remembrances of friends and family members they’ve lost. At the end of the week, the temple is burned.

There are less spectacular rooms, too. One gallery features a custom-made art car by the Five Ton Crane Arts Collective; it was built in parts, so it could fit inside the museum. The car – more specifically, a modified bus – has a silent, art deco-style cinema, a concession stand, and plush seats. It would doubtless be impressive in the desert. Indoors, it seems like something you’d find in the lobby of a suburban cinema.

Indeed, much of the art, while often fun to look at or play with, offers surface-level profundity, at best. Marco Cochrane’s Truth Is Beauty, a statue of a dancer inspired by “feminine energy and power that results when women feel free and safe,” would look more at home on the walls of a coffee shop than in a museum.

Atkinson says that the art on view should be exempt from criticism.

“I can imagine that people will judge this exhibition on the curation, but I don’t think that you can judge an artist negatively on work that was created to last for a single week,” she says. “The audience these are created for is for specifically that audience in the desert.” Art made for the contemporary art world, in other words, should be judged by the standards of contemporary art critics and buyers. Art made for Burning Man isn’t designed for judgment at all.

That’s not quite fair to contemporary art, which often includes performances and temporary installations, or to the art of Burning Man, which is often quite good. But the point – that these works should be appreciated for their craftsmanship and whimsy – is hard to argue with. Most people won’t be able to experience the fun of actually attending Burning Man; “No Spectators” is an excellent next-best thing.

Want more stories like this? Sign up here. Follow STYLE on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter

Sculptures transferred from their Nevada desert context create an awe-inspiring sight at the Renwick Gallery’s ‘No Spectators’ exhibition