Images of spectacular mass games captured in secretive North Korea

Despite being in a secretive state, British photographer Jeremy Hunter captured images of North Korea's spectacular Arirang mass games

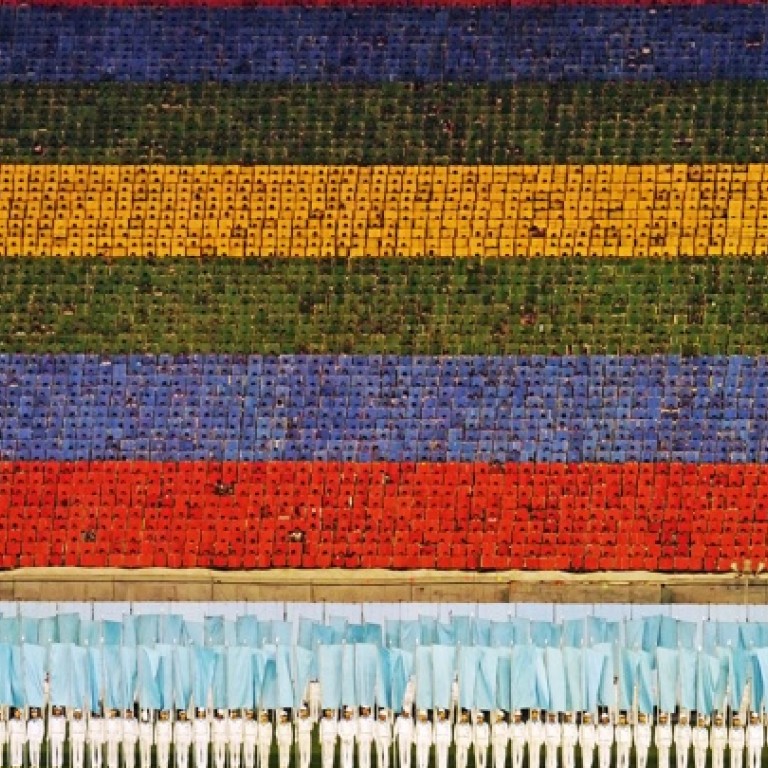

In a gigantic stadium, an audience of 150,000 enjoys a 120-minute spectacle, with tickets costing as much as €300 (HK$3,000). The show itself, boiled down from 250-million man hours of gymnastic effort, features spectacular scenes of seamlessly choreographed human mosaics followed by a grand fireworks display as the finale.

For British photographer Jeremy Hunter, however, North Korea will forever be associated with the Arirang, sometimes translated as the mass games.

While most of the small number of media workers who have made it to Pyongyang have had to conceal their identity, Hunter openly set out to capture images of the Arirang. In the process, he also managed to gather an insight into the divide between the regime "loyalists" and the "peasants" during his nine-day stay.

"It is incredible - every breath of every performer was co-ordinated … it [Arirang] eliminated individual will," said Hunter, a Unesco-award winner who has spent 35 years photographing rituals and ceremonies in 65 countries across five continents.

Every breath of every performer was co-ordinated … it eliminated individual will

Each of the show's scenes - which changed every 20 seconds - consists of about 100,000 performers, including 50,000 teenagers in the background and members of the military moving in the foreground. Each of the performers holds a flip chart of 150 pages to form collective pictures.

A glorified version of the nation emerges through the show, which tells stories infused with politically invigorating messages. One showed a smiling portrait of "eternal leader" Kim Il-sung, while another was a pair of pistols the late Kim's widow handed down to heir Kim Jong-il, father of incumbent Kim Jong-un. The cityscape of Shanghai was also featured to highlight the country's close ties with China.

"Arirang shows how we can work together as one to achieve anything we desire," the central message read in the finale, accompanied by bombastic fireworks exploding above the May Day Stadium, which has a capacity more than one and a half times that of the 91,000-seat Bird's Nest National Stadium in Beijing.

"The show was designed for North Koreans, it is their feel-good factor," says Hunter, 69, of the games, which involve six months of rehearsals. "It is one of the most incredible scenes I have ever seen."

[Video: Arirang mass games from 2012 on YouTube]

While North Korea is known for its secrecy, Hunter, who entered Pyongyang as a tourist, said he got to shoot the photos from a prime location with the help of a North Korean loyalist, being honest about his intention as a media professional. "I told her I wanted to photograph Arirang to add it to my archive of celebrations around the world," Hunter says of his tour guide, whom he describes as a tall and modern North Korean woman. "I said I wanted the best position and she helped me to get the seat, with a 90-degree angle to the scene."

He paid €300 for each of the two shows he went to and came up with his latest photography project, which recently went on show at the Atlas Gallery, London. Some of the works are to be shown when the gallery exhibits at the first Hong Kong incarnation of the Art Basel fair at the Convention and Exhibition Centre next week.

The celebration was first staged in 2002, and displays are put on several times during August and September every year. There are four kinds of seating available to tourists, with the cheapest going for €80 in a country where the average family lives on less than US$900 per year.

Hunter finally made it to Pyongyang at the second attempt by joining a nine-day tour organised by a specialist British travel agency in August 2011. An earlier attempt to get in as a photographer failed. "I had made an official application to North Korea's embassy in London and had a very positive meeting with a secretary," Hunter said. "But eventually he said it was not possible for an official approval."

"They [the North Koreans] want to make sure you only see and photograph what they want you to see," said Hunter, explaining why tourists had to leave behind mobile phones and some camcorders in Beijing before they boarded the Russian aircrafts of Air Koryo. There was another tour guide whose job was largely to monitor if anyone in the group sneaked pictures.

"There are some cameras which do not look like [they are advanced]," he said, when asked what equipment he was able to get in to capture the high quality photographs of the Arirang photos. He gave no further details.

The woman guide who got Hunter a seat was the image of North Korea's elite class, the highest among the three-level social system, followed by the working and peasant classes.

"You would not find her strange if she was sitting here", referring to a London coffee shop where Hunter was interviewed. "She speaks very fluent English, holds a designer handbag and has a mobile phone."

His description of the guide is markedly different to that of the typical North Korean who, according to international human rights reports, relies on 395 grams of rationed cornmeal a day, resulting in malnutrition that leaves the average North Korean 10cm to 12cm shorter than Asian neighbours.

Even the daily necessities of life for those in London or Hong Kong are out of reach to all but the loyalists in North Korea.

"In Pyongyang, tourists can go on the subway. Your fellow passengers all belong to the loyal-and-elite class," says Hunter, who describes his fellow passengers as looking "smart in white shirts, ties and blue trousers".

They also wear badges specifying their different sub-status within the elite, in a system structured similarly to the British honours system.

So where are the others, those who belong to the working or peasant class? "You won't see them in Pyongyang. They are all living in the countryside," he says.

Hunter still managed to catch a glimpse of impoverished ordinary North Korea while travelling in a bus arranged by the authorities. "When we toured around in a bus, I saw workers cutting grass along the roadside," he said. "They cut it using scissors - because they need to add the grass into their diet as a supplement."

Food was a source of distress for Hunter, who along with his fellow tourists was served up a range of delicacies in a country where human rights groups say has had outbreaks of cannibalism amid extreme hunger.

"I had some of the best Asian food I have ever had … comparable to the top Asian food in London," said Hunter, who admits he loves Asian food so much he "can rely on it for three meals a day, for the rest of my life".

"We were treated like Gods."

According to Hunter, the meals - akin to South Korean cuisine and always excellent - would usually consist of bulgogi (marinated beef, usually barbecued), naeng myeon (cold noodles) and kimchi (pickled vegetables).

The quality food is believed to have been imported from neighbouring China.

Accommodation, on the other hand, was not so modern. Hunter stayed at the Koryo Hotel, reputedly Pyongyang's best.

"It was like those hotels I stayed in during the Cultural Revolution in China," said Hunter, who worked as a producer and journalist and reported from China during the 10 years of social upheaval that ended in 1976.

"The hotel had its own power source since supply is an issue in North Korea, where all street lights go off at nighttime. It is complete darkness."

If that all sounds like a wartime curfew, consider this: Hunter noted that the infrastructure in North Korea is on a war footing.

"The main highway is like a runway at the airport, with no marking," he says, adding that the wide road "can cater for jets any time".

Besides war, the Pyongyang authorities are also on guard against the possibility of a "Korean spring", a parallel to the Arab spring uprisings against despotic regimes in the Middle East and North Africa.

"It's not a question of if, but when," Hunter says of the chances of underprivileged North Koreans demanding change. "The peasant class are getting the chance to know more about the outside world, thanks to global technology.

"In the south of the country, people have radios and they can tune to some stations in neighbouring China. They begin to recognise there is another style of life across the border, which they might prefer."