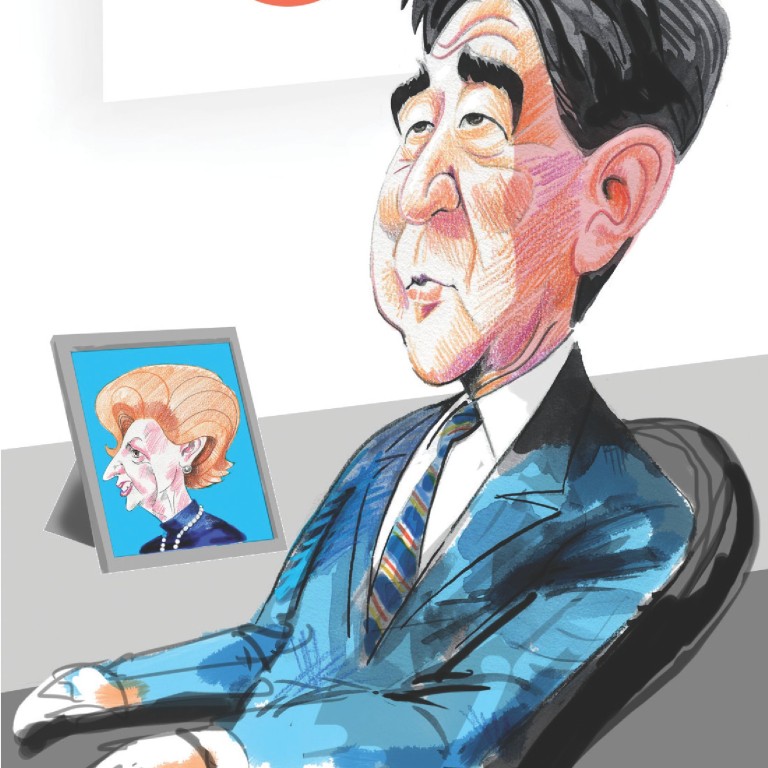

Shinzo Abe set to reshape Japan with conservative agenda

Japan's PM can dominate politics for years by exploiting the weaknesses of his opponents, much like Margaret Thatcher did in the 1980s

Nearly seven years ago, Shinzo Abe shuffled out of the official residence of the prime minister of Japan a beaten man. Ground down by a failure to push through his pet projects and an inability to fill the large political shoes of his immediate predecessor, Junichiro Koizumi, Abe had lasted exactly 365 days and departed citing a debilitating stomach complaint as the main reason for his resignation.

"At this point, it looks very much as if the Liberal Democratic Party and Mr Abe will win big … which will give him a great deal of power," said Steven Reed, a professor at Chuo University who specialises in Japanese politics. He was speaking ahead of today's elections.

"In many ways, it is like Mrs. Thatcher when she won in 1983, and I think that if the LDP allows Mr Abe to lead the party as he has been doing so far then he could go on to change Japan as much as Mrs Thatcher did in Britain."

Abe is benefitting from an opposition that is in disarray, in much the same way that Thatcher's political opponents were fractured in 1983, although there are still questions over the cohesiveness of the Japanese leader's party.

"If he can hold the party together, then Mr Abe could head the LDP for the next 10 years," Reed said. "And that would be something that no other modern Japanese leader has done."

Given the failure of his first stint in power, it would be a remarkable comeback.

Born in rural Yamaguchi Prefecture, Abe moved to Tokyo as a boy and studied political science at Seikei University and public policy at the University of Southern California. He worked for Kobe Steel for three years from 1982 before beginning to dabble in Japan's political world.

Abe's father and grandfather were both politicians and his mother, Yoko Kishi, is the daughter of Nobusuke Kishi, who was imprisoned by the Allied Occupation authorities after the second world war for serving in the cabinet of General Hideki Tojo. But he was released to counter the spread of communism in Japan and went on to be prime minister from 1957 to 1960.

Abe was first elected to the Diet in 1993 and was director of the Social Affairs Division and chief cabinet secretary in Koizumi's administration. On September 20, 2006, he was elected as the youngest Japanese prime minister since 1941.

"By his own admission, Abe was too insistent on doing the things that he wanted to do and he failed to heed the demands of the electorate in his first term in office," said Jun Okumura, an international relations analyst with the Eurasia Group.

True to his conservative roots, Abe denied that "comfort women" were abducted and forced to provide sex to members of the Imperial Japanese forces in the early decades of the last century. Criticism from South Korea of school textbooks that reflected that stance was dismissed as foreign interference in domestic Japanese affairs.

Abe was also behind a bill to promote nationalism and "love of one's country", while he was opposed to permitting a woman to assume the imperial throne.

And while Abe said it was important for Japan to have closer ties with its neighbours in east Asia, that did not stop him from paying his respects at the Yasukuni Shrine, dedicated to Japan's war dead and considered the last resting place of the souls of soldiers and Class-A war criminals, in April 2006, about five months before assuming office.

Similar controversies have swirled around his second administration, installed after the LDP decimated the Democratic Party of Japan in December's election, although Abe himself has remained largely above those particular frays. The priority, at least in the early days of this government, has been the economy.

"I think he has put together a very well-crafted policy package that has been easy to explain to the electorate, clear and coherent," said Okumura.

He has also been remarkably fortunate, Okumura points out, as the improvements in the Japanese economy have moved exchange rates and the equity market at the same time as the US has seen an economic recovery and stability has returned to Europe.

That translates into a feel-good factor at home and, according to the polls, as much as 43 per cent of the electorate will vote for the LDP today, with a further 8 per cent backing New Komeito, its ally in the ruling coalition.

The DPJ, on the other hand, has the support of just 7 per cent of the electorate.

"It's difficult to say what the issues have been for the electorate because the opposition parties have been so fractured and unable to identify any significant highlights of their own campaign issues," said Okumura.

The DPJ, for example, has failed to focus debate on nuclear power, despite the issue having a huge resonance with the electorate 28 months after the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

Similarly, there has been little discussion of Japan's participation in discussions on the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the free-trade pact which some fear will devastate Japan's agricultural sector, or Japan's foreign policy and national security issues at a time when Tokyo's diplomatic relationships with its immediate neighbours are at all-time lows.

Abe's candidates are expected to romp to victory today, giving the same political party control of both houses of the Japanese Diet for the first time in six years and shattering the impasse that has delayed and blocked social and political reforms.

With that mandate, Okumura believes Abe will attempt to impose changes in the areas of labour reform, agrarian reform, healthcare and women in the workplace.

"If he is able to achieve half the things that require his attention, then there will be a transformation in Japanese society and Abe will go down as a historical figure," Reed said. "But even with that elusive two-house majority, I think it will be difficult to conclude such massive changes."

Most significantly, Okumura believes that Abe will be frustrated in the issue that is closest to his conservative heart: reform of a constitution that nationalists here believe was imposed on Japan by the Allies in the aftermath of the second world war.

Any significant change in the constitution would inevitably involve Article 9, which outlaws war as a means to settle international disputes, and Buddhist-backed New Komeito would oppose any such campaign.

"I think Mr Abe will try to go forward, but what he can't afford to do is to force New Komeito to part ways with the LDP," Okumura said. "He cannot afford to lose what equates to around 10 per cent of the voters in this election and all elections in future.

"I suspect he will work on New Komeito to try to loosen the ban on collective defence, but through interpretation of the constitution rather than attempting an amendment," he added.

That may be a disappointment to Abe who hopes to reinvent his nation, but real change in other areas of Japanese society are within his grasp.