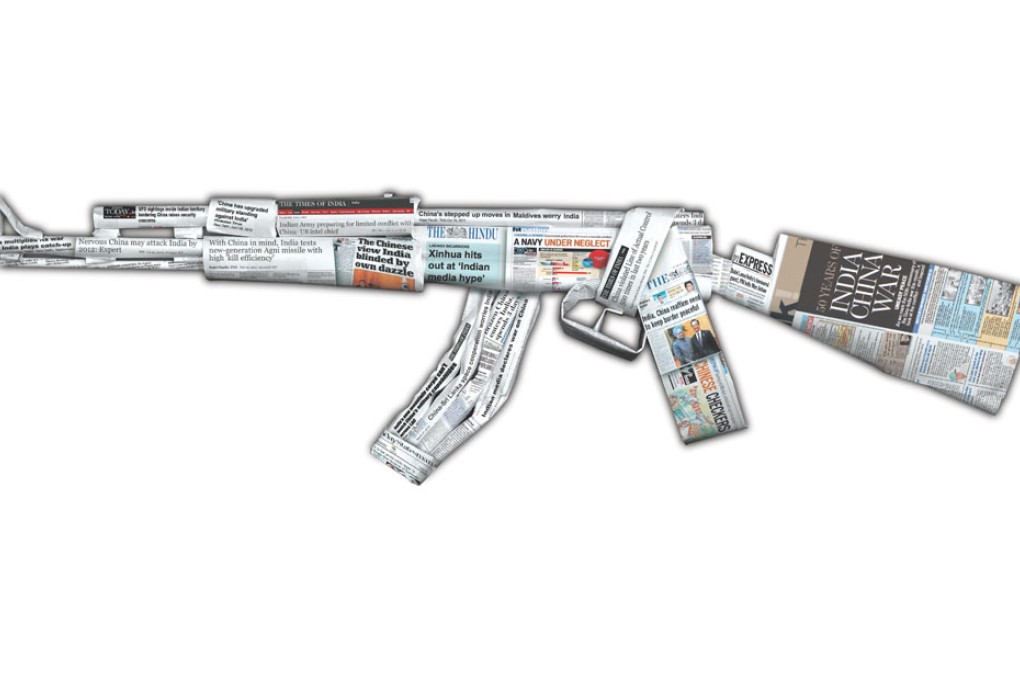

Media on both sides share the blame for India-China tensions

That Indians and Chinese view each other's countries negatively is largely the fault of newspapers and TV, which realise tension sells

One of the greatest, albeit probably apocryphal, stories on the power of the media is the supposed exchange of cables between media baron William Randolph Hearst and Frederic Remington - an illustrator Hearst had hired for his newspapers - just before the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Hearst had recruited Remington to send him illustrations from Cuba. After spending some time there, Remington decided to return home. Before leaving Havana, Remington sent Hearst a telegram that is said to have said: "Everything is quiet. There will be no war. I wish to return."

Legend has it that Hearst replied: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures, and I'll furnish the war."

Soon after, the American battleship USS Maine, which was sent in as a symbol of American support to Cuba's struggle for independence, exploded and sank in Havana harbour for reasons unknown to this date. Papers owned by Hearst and Pulitzer, however, promptly decided it was the handiwork of the Spanish, and launched a renewed media campaign demanding retaliation by America. Within a couple of months the United States declared war on Spain over Cuba. The war had been delivered.

Media observers on both sides often complain that the reporting of China in an influential section of the Indian media in the past few years would make Hearst proud.