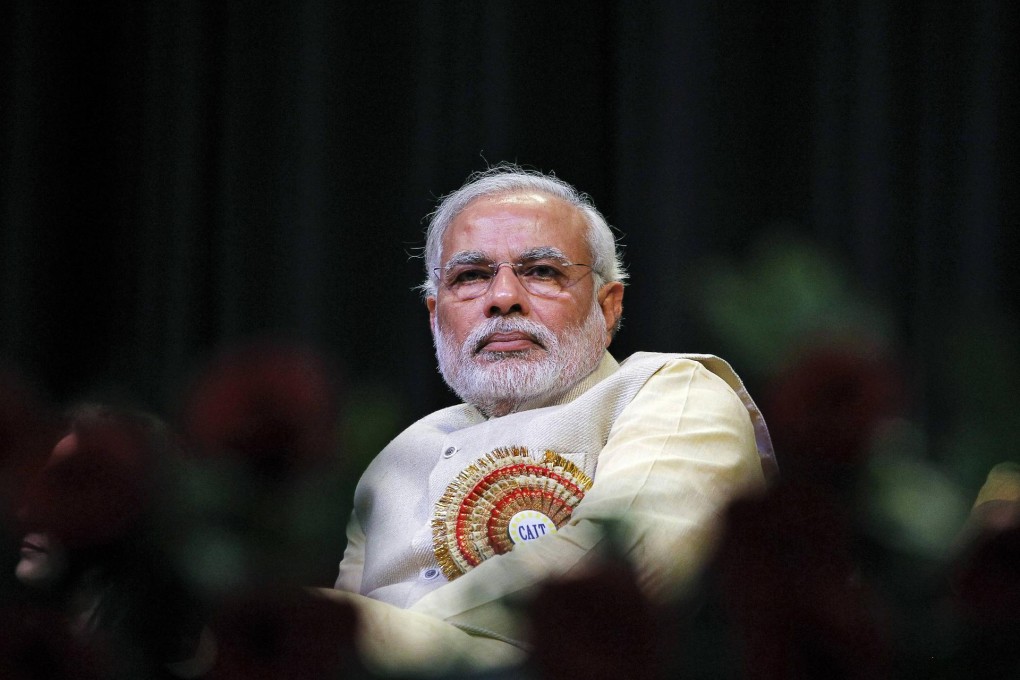

India's likely next leader Modi seen implementing Thatcher-like reforms

Advisers to the front runner, Narendra Modi, expect him to slash size of government if the opposition wins elections starting today

When Indian opposition leader Narendra Modi gave a speech on the virtues of smaller government and privatisation on April 8 last year, supporters called him an ideological heir to former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who died that day.

Modi, favourite to form India's next government after elections starting today, has yet to unveil any detailed economic plans but it is clear that some of his closest advisers and campaign managers have a Thatcherite ambition for him.

"If you define Thatcherism as less government, free enterprise, then there is no difference between "Modinomics" and "Thatcherism", said Deepak Kanth, a London-based banker now collecting funds as a volunteer for Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Kanth, who says he is on the economic right, is one of several hundred volunteers with a similar philosophy working for Modi in campaign war rooms across the country. Among them are alumni of Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan trading floors.

"What Thatcher did with financial market reforms, you can expect a similar thing with infrastructure in India under Modi," he said, referring to Thatcher's trademark "Big Bang" of sudden financial deregulation in 1986.

Modi's inner circle also includes prominent economists and industrialists who share a desire to see his BJP draw a line under decades of socialist economics, cut welfare and reduce the role of government in business.

The BJP is due to unveil detailed economic plans today and is expected to make populist pledges to create a massive number of manufacturing jobs and to restart India's stalled US$1 trillion infrastructure development programme.