‘They told us it was for the good of mankind’: the troubling legacy of nuclear testing in the Pacific

Long after the US, Britain and France stopped their testing programmes,the Marshall Islands atoll remains contaminated today

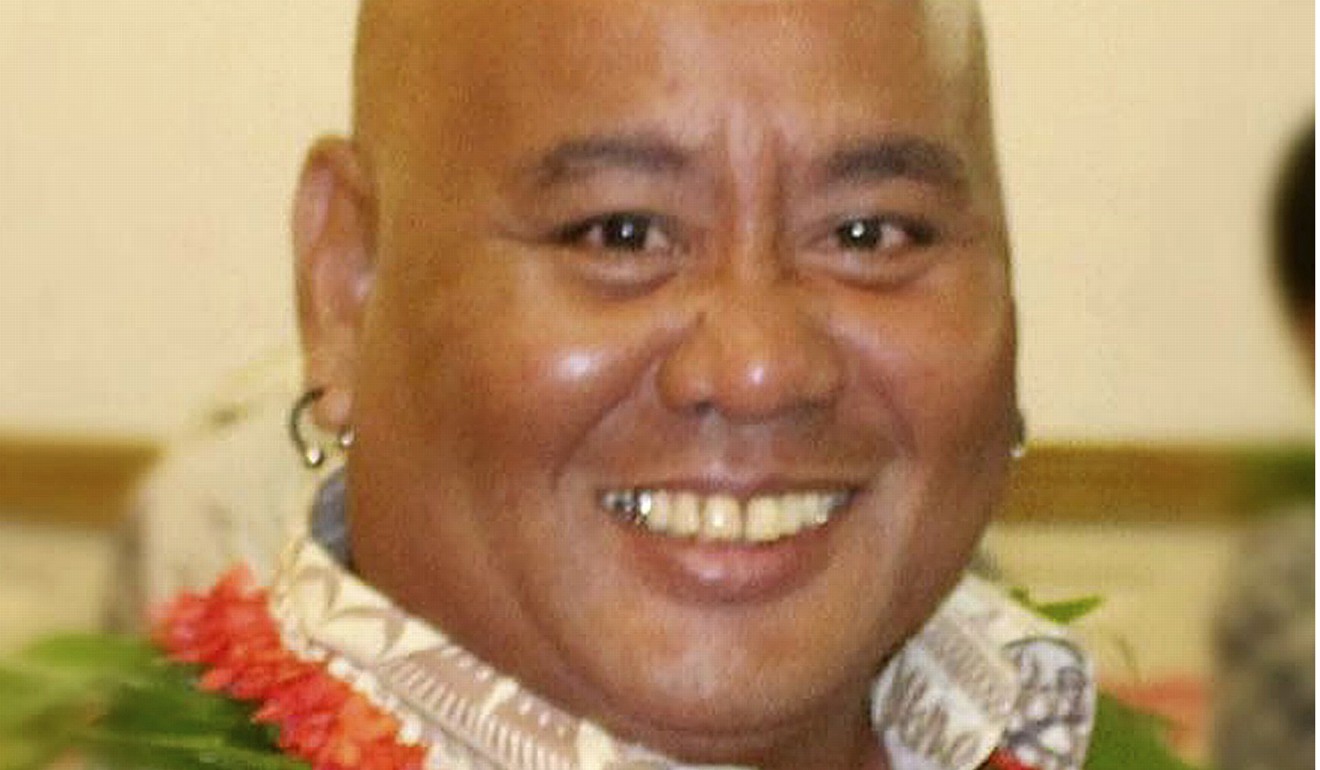

As a young boy growing up on Bikini Atoll, Alson Kelen spent idyllic days playing on the beach and fishing.

His grandfather built canoes and his father tended the land. With fewer than 150 people on the remote Pacific island it was a close community, he says, with few signs of the former US nuclear testing programme other than the concrete bunkers he was told to avoid and the sunken ships in the lagoon.

But in 1978, when Kelen was 10, officials evacuated everybody. It turned out they had been premature in declaring the Marshall Islands atoll safe again for humans. Radiation levels were still dangerously high.

More than 70 years after the first tests, the atoll remains contaminated today. It’s part of a troubling nuclear legacy that continues to affect islands and people across the Pacific long after the US, Britain and France stopped their testing programmes there.

As nuclear tensions rise in the Asia-Pacific region, Kelen and others are reflecting on that legacy anew.

Kelen says that if the threats do escalate to a nuclear test or even an attack, “it would be a huge, huge disaster”.

The 49-year-old says he has no idea if his exposure to radiation during the four years he lived on Bikini as a boy has affected his health. He says scientists used to test him and his family regularly, but stopped within a couple of years of them leaving the atoll.

Scientists have calculated that about 1.6 per cent of all cancers developed by Marshallese people exposed to radiation can be attributed to the nuclear tests. For some islanders who were close to the blasts, the rate rises to 55 per cent.

The nuclear tests exacted an enormous social toll on Bikini residents and their children, who are now scattered across the Marshall Islands and beyond and have been left without a homeland. Kelen says they’ve lost the ancestral land that’s central to their identity.

“Ninety per cent of Bikinians have never seen Bikini. It’s a legend; it’s a fairy tale,” he said. “They know more about Hawaii and the US mainland than Bikini.”

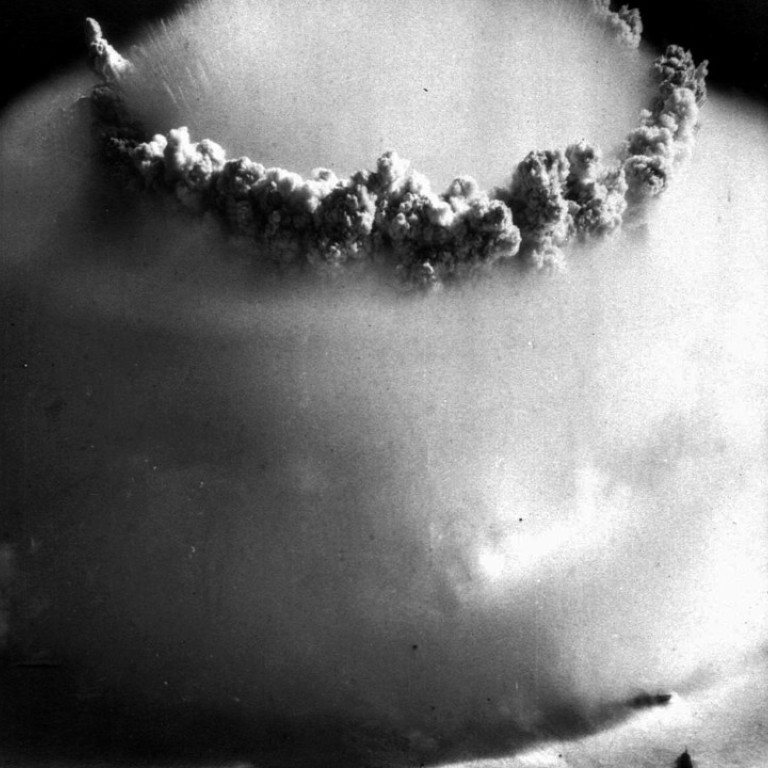

The US government first asked Bikini residents to leave temporarily in 1946. It then conducted a series of tests over a dozen years, including detonating a massive hydrogen bomb hundreds of times more powerful than the nuclear bombs the US dropped on Japan during the second world war.

The inhabitants were moved to other islands that proved inhospitable. Kelen’s family eventually ended up in Majuro, the capital. He says his parents always planned to return to Bikini but got to spend just four years there before being told to leave again. Kelen’s father died two years ago and his mother, now 93, is too old to travel.

“They told us we were relocated from Bikini for the good of mankind, to bring peace to the world. But I think nuclear is the same as climate change,” Kelen said. “It benefits the big countries and ruins the small countries.”

Bikini residents have received some compensation from the United States. But many people, including Marshall Islands President Hilda Heine, say it’s not enough.

Heine said in a speech this year that the removal of the Bikini residents produced “inconsolable grief, terror and righteous anger” that had not diminished in the seven decades since, and had been exacerbated by the US being dishonest about the extent of the radiation and its effects.

Some 5,000km away in Tahiti, French Polynesia, Roland Oldham is also grappling with nuclear testing’s legacy.

He is president of Moruroa e tatou, an organisation that represents victims of French tests at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls. The nuclear tests lasted 30 years, ending in 1996, the year the United Nations adopted the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

Studies have shown that people in the region during the tests had an increased risk of developing thyroid cancer. But information on radiation exposure remains classified, making it hard to estimate the risks.

Oldham says those who worked directly on the testing programme suffered high rates of cancer and other health problems. He says it’s difficult to get good statistics on the health effects on the broader community because of the continuing secrecy.

Much of the later testing was carried out underground, but some radiation has leaked. Oldham fears the problem could get much worse because parts of the atolls are in danger of subsiding.

Oldham, 66, says he sailed around Moruroa while completing his military service with the French navy in 1970. He says he never saw or felt anything, and doesn’t know if he was exposed to radiation or the extent of that exposure.

Oldham says the heated rhetoric between the leaders of North Korea and the United States has made much of the Pacific vulnerable at the moment because of US military bases in places like Guam, Japan and South Korea.

He said: “the day the two guys throw a punch at each other, the whole area will be suffering.”

He says he worries that mankind is headed toward its own destruction by nuclear weapons.

“At some stage I want to be sick, when I observe the things happening in front of my eyes,” he said. “What a world. What a crazy mess.”