Inside the DMZ ‘village’ where Donald Trump, Kim Jong-un may meet

The so-called peace village has had a violent history, which is played by the US and South Korea for the sake of the tourists

Before President Donald Trump and North Korea’s Kim Jong-un hold their summit in May, they must first agree on a secure and convenient venue.

Pyongyang? Beijing? Mar-a-Lago? All unlikely. Many experts agree the only logical place is Panmunjom, a heavily guarded “truce village” in the demilitarised zone that divides the Koreas. It is where the North and South have occasionally held talks.

Although generally peaceful, Panmunjom has been the scene of defections and violence over the years.

It is in the middle of the heavily mined, 4km-wide DMZ, roughly 51km (32 miles) northwest of Seoul and 161km (100 miles) southeast of Pyongyang.

Within Panmunjom, two imposing buildings – the Freedom House on the south side and Panmon Hall on the North – stand on opposite sides of a plaza. In between are seven blue and grey meeting halls, with the Military Demarcation Line running through them. On either side, guards for the United Nations face their North Korean counterparts.

During a July visit by a group of media, a UN guard wearing aviator glasses instructed the group on taking photos of the North and South Korean guards.

“Do not make any hand gestures to the North,” the guard warned. “Do not go beyond the soldier beside you on the left or right.”

Avoiding provocation is the name of the game at Panmunjom.

When the Korean war armistice was signed there, the two sides established the site as neutral ground.

Guards for the two sides kept an eye on each other at several checkpoints. This included one manned by the UN that had its view blocked by a tree, which it regularly trimmed. When it did on August 18, 1976, North Korean troops attacked the tree trimmers with axes.

Two US Army officers were killed. The peninsula was thrown into crisis mode. In Japan and South Korea, US force were put on alert. It later became known as the “Axe Murder Incident”.

In 1984, a Soviet translator in North Korea tried to defect by fleeing across the Military Demarcation Line. North Korean troops opened fire and UN troops shot back. The translator made it to safety, but four North Koreans and a South Korean were killed.

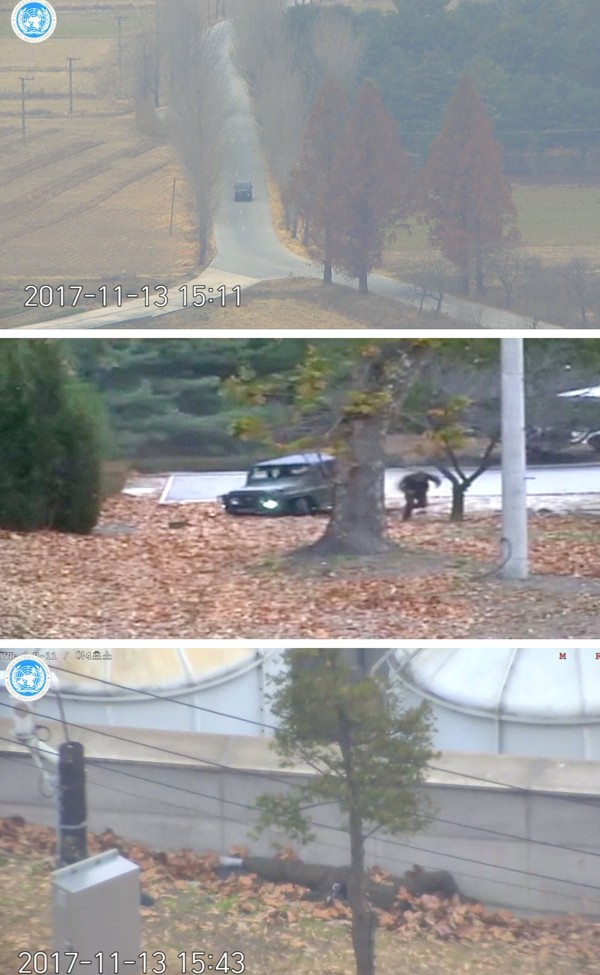

Panmunjom was mostly quiet until last November, when a North Korea soldier fled across the line. His comrades opened fire, hitting him, but he managed to reach the south.

Every year, roughly 1.2 million tourists visit the DMZ. Visitors must first stop at Camp Bonifas, the UN base outside the DMZ that is named after one of the officers killed in the Axe Murder Incident.

There, tourists are treated to a video on the history of bloody incidents at Panmunjom. “So the JSA is evidently the most dangerous place to be in the Republic of Korea,” the announcer said during a tour in July.

Balbina Hwang, a Korea specialist in the US State Department during the George W. Bush administration, said the UN likes to play up the danger, in part, so US visitors feel their tax dollars are being spent wisely.