India’s black money market booming a year after Modi’s controversial cash crunch

When India declared most bank notes unusable a year ago in what was sold as an effort to flush out tax cheats, one steel manufacturer was so spooked he decided to do business by the book in future.

But 12 months on from the shock move, the industrialist says he has gone back to cash under the table at the insistence of his buyers – undermining government claims that the bold scheme has cleaned up India’s graft-ridden economy.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision last November to withdraw India’s high-value rupee bills was intended to root out a culture of tax evasion so widespread it had become the norm.

His Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had won the 2014 election on a promise to fight corruption, which had led to popular disillusionment with the previous government.

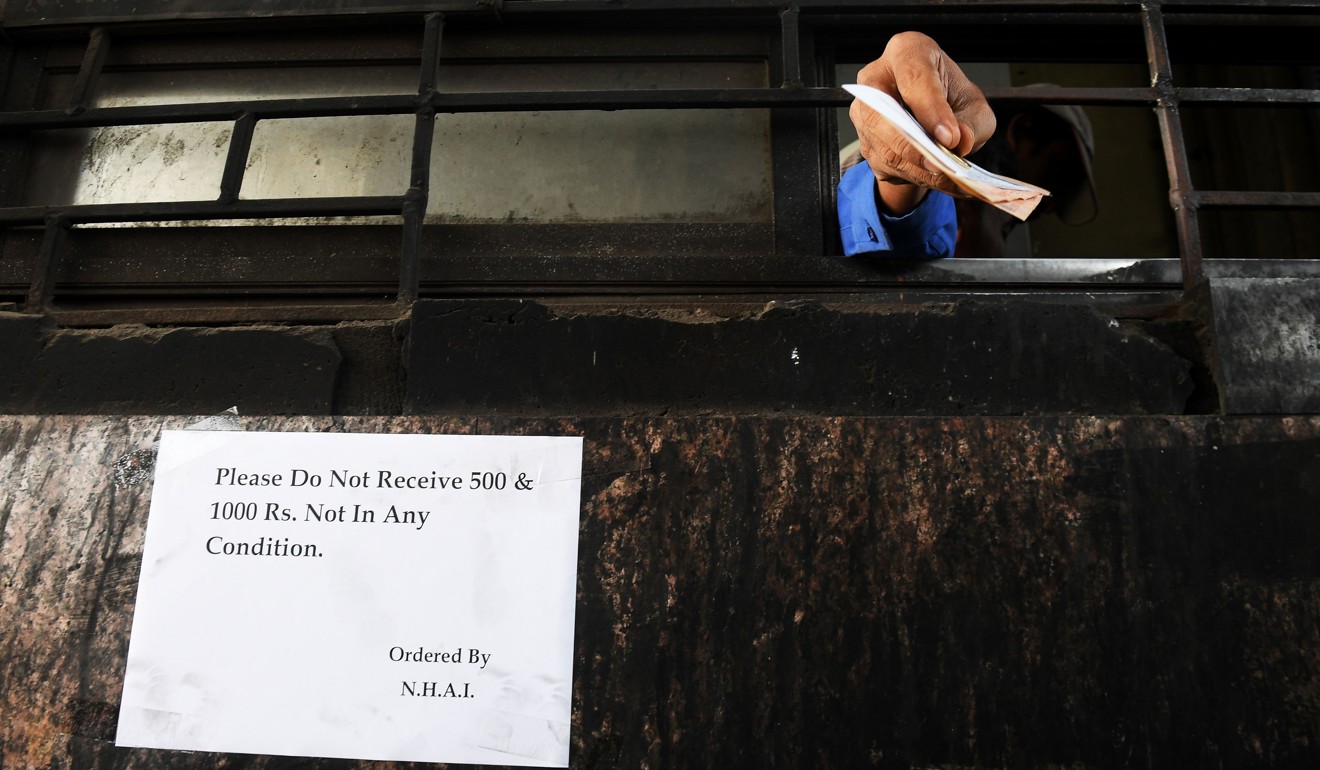

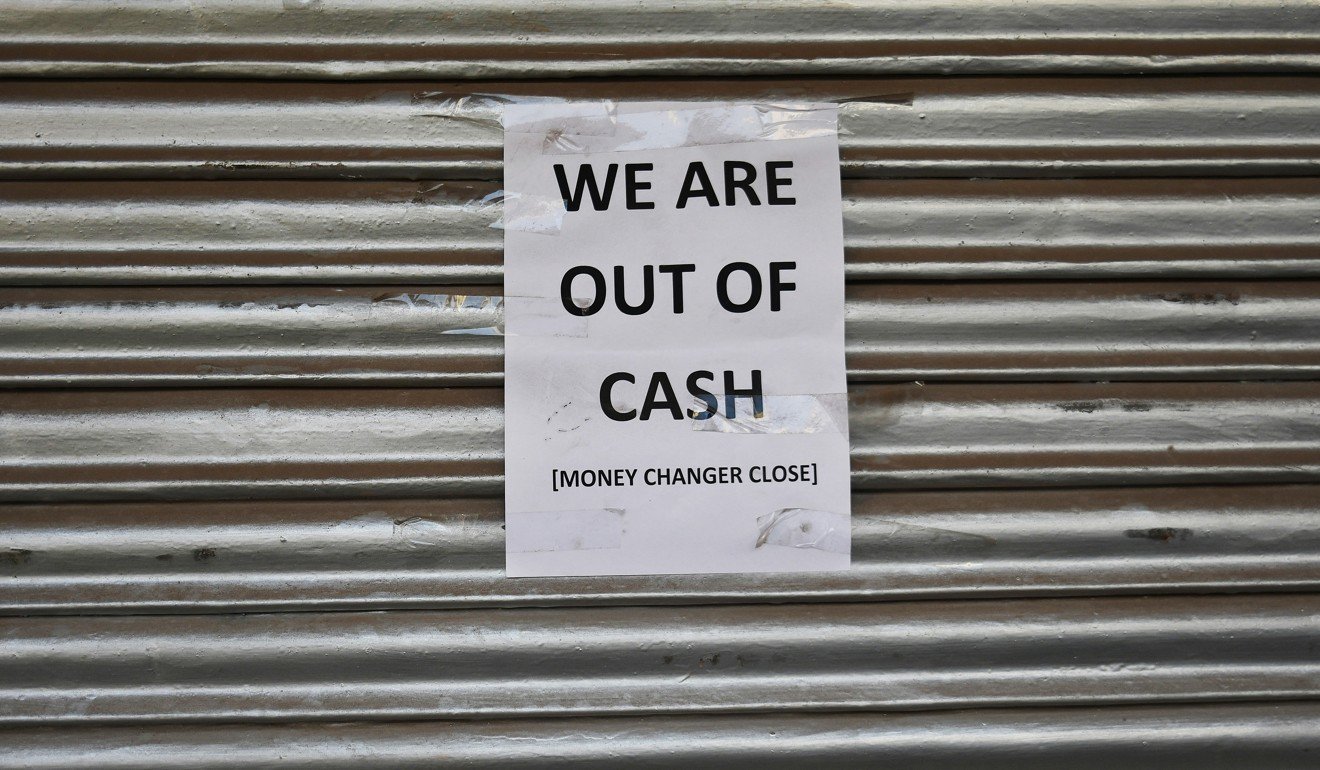

But the move to ban 500 and 1,000 rupee (US$7.50 and US$15) notes wrought havoc on businesses in Asia’s third-largest economy, causing growth to slump to levels not seen since Modi was elected.

Now, as businesses from roadside stalls to wholesalers rekindle their love affair with cash, Modi is coming under pressure to explain whether the most controversial policy of his tenure was worth the economic pain or the hardship it caused in the country’s poor.

The steel producer, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said his efforts to keep business above board backfired when his buyers insisted on paying cash – and keeping their payments off the books.

“They said, ‘we have cash at home, and if you want to be paid, we can pay you in cash immediately, but we cannot arrange a bank payment’,” he said.

The government had hoped the surprise move, which meant high-value notes could not be spent and instead had to be banked, would encourage a switch to traceable digital payments in a country where just three per cent had been paying taxes.

Modi personally championed credit and debit cards in the aftermath of demonetisation, beaming down from billboards encouraging Indians to embark on a digital revolution.

But sales from plastic have declined 13 per cent from highs in December 2016, when new cash notes were scarce.

Mobile banking figures for August, the latest data available, showed US$16 billion in transactions – a 20 per cent drop compared with November.

Sanjay Moria, a tea vendor in central Delhi, said at least half his income in the weeks after demonetisation came through a popular payment app, but since then, digital sales had plunged.

“I’ll take any form of payment, but people are mostly back to paying in cash,” he said, as office workers sipped hot spiced tea from small paper cups.

Many poorer Indians, reliant on cash, were left scrambling to buy basic necessities as their meagre savings evaporated in an instant.

“Was it worth it? Certainly not,” said Sunil Sinha, principal economist at India Ratings & Research. “It brought huge pain and disruption. People lost lives, lost their livelihoods.”

Authorities also expected that a portion of non-tax payers would fail to bank their unusable cash for fear of exposure.

But in August the Reserve Bank of India announced that 99 per cent of the devalued bills had been returned, undermining Modi’s claim that stashes of black money would be uncovered.

Now traders say they are operating much as they did before the ban, with cash once again king, as fears of being stung by the taxman have faded.

“We’re in a wait and watch phase before we decide if we should increase the cash portion [of the business] or not. It depends how closely the government monitors this,” said a dry fruit importer in a traditional market in Delhi’s old quarter. “Everyone does this. This is how business is done in India.”

.png?itok=arIb17P0)