High hopes for first-ever Indonesian author vying for Man Booker glory

The 40-year-old is up against revered writers like Orhan Pamuk and Kenzaburo Oe, both past recipients of the Nobel Prize in Literature

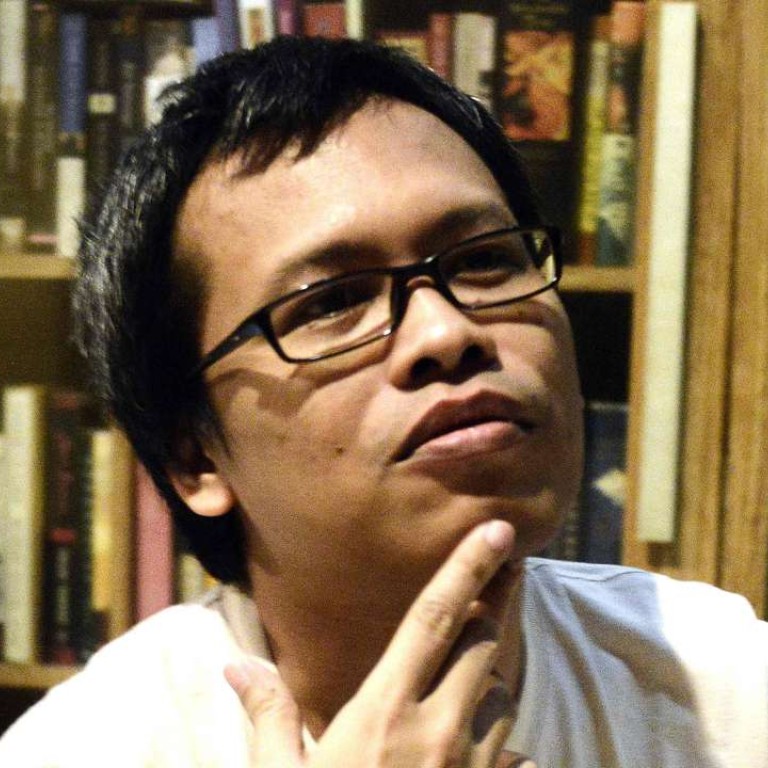

Already compared to literary heavyweights Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Haruki Murakami, great expectations weigh on Eka Kurniawan, the first Indonesian ever nominated for a Man Booker International Prize.

The 40-year-old is up against revered writers like Orhan Pamuk and Kenzaburo Oe, both past recipients of the Nobel Prize in Literature, but there is a growing buzz about the works of this little known author.

At home, titles of Kurniawan’s novels splashed across the back of trucks, while newspapers and magazines hail him Indonesia’s most exciting writer for a generation.

“My friends sent me pictures of the back of trucks bearing the titles of my books – these [trucks and the lives of the drivers] were an inspiration for one of my novels – and the fact my books are emblazoned there brought me to a state of euphoria, I got goosebumps,” he said.

Internationally, demand is such that he’s already attended the acclaimed Frankfurt and Melbourne Book Fairs.

I hope this is the case that Indonesian literature is really on the rise, because in the past 10 years I can feel the excitement

Despite this, Kurniawan says his inclusion on the longlist for the prestigious award, for Man Tiger – the story of a young man who gnaws his elderly neighbour to death – came as a “surprise”.

He will find out on Thursday if he has made the final six. The winning author and translator will also share £50,000 pounds (HK$551,100) in prize money, while all the finalists receive £1,000.

A shortlist nomination – or better still, a victory – will likely provide a much-needed international profile boost not just for Kurniawan, but for the nation’s literary scene.

“I hope this is the case that Indonesian literature is really on the rise, because in the past 10 years I can feel the excitement,” he adds.

Indonesian writers have long struggled for appreciation at home, let alone on the world stage. Many do not have the means to translate their books into other languages and attract publishers and readers abroad.

Yet theirs is a passionate desire to share their stories and the profession has flourished since Indonesia embraced democracy.

Kurniawan, who is now married with a young daughter, participated in the student protests that toppled the authoritarian regime in 1998. He says the wave of openness that followed the end of Suharto’s three-decade rule had an “enormous” influence on Indonesia’s literary evolution.

“I feel Indonesia is more open,” Kurniawan explains. “We can speak practically about many things, including politics, religion and other taboos like sex.”

Kurniawan’s own work is no exception: Man Tiger is a grisly, murderous tale, while Beauty is a Wound revolves around the communist massacres across Indonesia in the 1960s, a politically-sensitive topic to this day.

The vein of magic realism throughout his work has earned Kurniawan comparisons to legendary Colombian novelist Marquez, while others tout him as successor to Pramoedya Ananta Toer.

Pramoedya, who died a decade ago this month, is considered Indonesia’s greatest-ever writer. His legendary Buru Quartet – which he wrote behind bars during the Suharto years – earned him several nominations for a Nobel Prize for Literature, and acclaim overseas.

For all the high praise directed at Kurniawan, who is from West Java but now lives in Jakarta, it has been slow crawl from aspiring writer to Booker nominee.

He worked as a graphic designer and jobbing writer, but when Man Tiger was first published in Indonesian in 2004 – he concedes the readership really only extended to his circle of close friends.

It took a decade before it was translated into English and on bookshelves overseas.

The respected Southeast Asian scholar, Benedict Anderson stumbled on Kurniawan’s work and, impressed, urged him to translate his works and meet with a British publisher later describing him as “Indonesia’s most original living writer of novels and short stories”.

For many writers – language is a challenge. Indonesian is often second choice after local dialects. This limits exposure in a country where only one in 1,000 spends time reading, according to research by Unesco.

Publishing in English is the only avenue for global recognition and readership but for many the cost of quality translation remains too high, ensuring they remain off the radar of major international publishers.

But interest is growing – last year Indonesia was guest of honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair, an opportunity to showcase the literary culture and traditions at the largest publishing event in the world.

There’s a sense Kurniawan could encourage further interest. Barbara Epler, the head of his US publisher New Directions, predicted that if Kurniawan took off overseas he would be a “prime force” in getting more publishers interested in Indonesia, a sentiment echoed in his homeland.

“I hope he wins so that authors will rush to translate their books into other languages, promoting them to the world,” respected Indonesian poet Sapardi Djoko Damono said.

The shortlist for the Man Booker International Prize will be announced on Thursday and the winner on May 16.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)