Wang Yang, the party chief who transformed Guangdong

The first of a two-part series on Guangdong party chief Wang Yang looks at how he turned the province into a base for high-end manufacturing

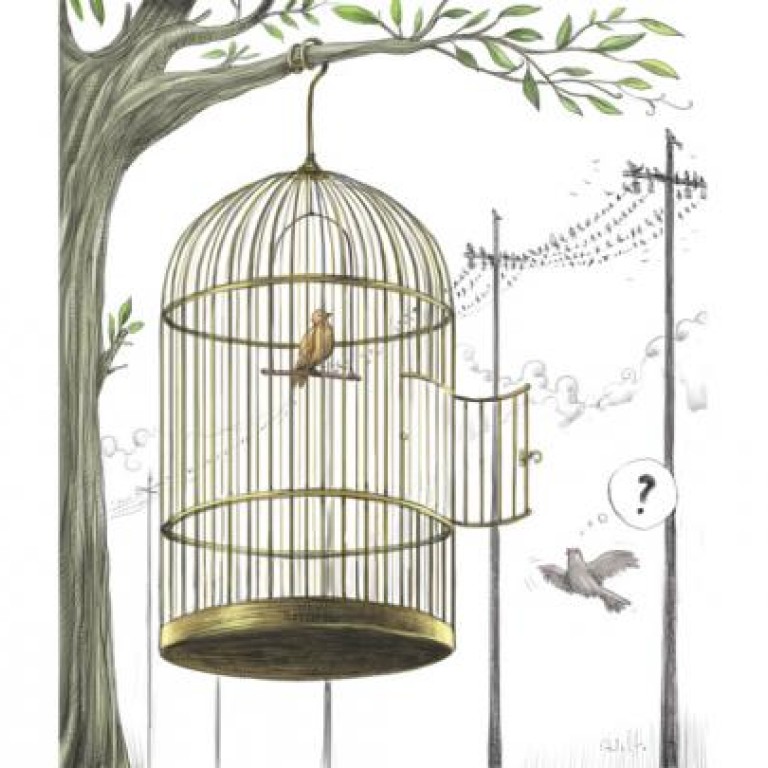

"Empty the cage and let the right birds in" was Wang Yang's main economic prescription when he became Guangdong's Communist Party chief in December 2007.

Wang's courage to break away from a model that had delivered three decades of double-digit growth in the province's gross domestic product won him a reputation as a liberal reformer and made him stand out among the traditionally GDP-obsessed provincial governors.

His advocacy of free-market reform in Guangdong also contrasted strongly with former Chongqing party chief Bo Xilai's fervent championing of an economic model that largely relied on state-owned firms and government to spur growth.

With Wang's five years in Guangdong nearing an end, his cage-and-bird theory has become a catchphrase that has spread to other coastal provinces such as Zhejiang and Jiangsu , which have also relied heavily on export manufacturing. Analysts said it was also likely to be remembered as a manifestation of President Hu Jintao's "scientific concept of development" - a key legacy of his 10-year reign.

The provincial party mouthpiece has hailed Wang's success in turning the province into an international base for high-end manufacturing and services, with factories producing trains, cars, LCD screens and other hi-tech products. At the same time, it said, the province has also boosted its heavy industry sector with new steel and petrochemical projects.

The Guangdong model, which echoes the central government's repeated calls for economic restructuring, has won endorsement from many leading mainland economists. Li Yining , one of the pioneers of market reform, praised Guangdong's focus on industrial innovation and upgrading as an inspiration for other provinces.

However, it is too early to conclude that Wang's pet slogan has put Guangdong's economy on the right track, especially as the province is yet to show solid signs of recovery from a substantial slowdown, and with little evidence that wealth gaps and regional differences within the province are narrowing.

Wang is known for his reluctance to use GDP growth as a gauge of economic achievement, lamenting the way some regional governments artificially drove up GDP figures in a 2009 article in the party mouthpiece . At the beginning of this year, to show he was more concerned about transformation and industrial upgrading, Wang even avoided any mention of GDP growth in his 15,000-word government report to the provincial people's congress.

It is still noteworthy, however, that the province's economic growth slowed to 7.9 per cent between January and September, one of its weakest periods in a decade. In its first four years under Wang, the province's economic output grew 47 per cent to 5.3 trillion yuan last year.

Soon after he became Guangdong's party secretary, Wang laid out his plan to relocate lower-margin manufacturing industries to the province's less developed regions, such as in the north, and implemented tighter labour and environmental regulations.

In March 2008, on a trip to Dongguan - then a prosperous manufacturing hub famous for its many factories churning out shoes, clothes, textiles, furniture and toys - he warned that "if Dongguan does not start to transform its industrial structure today, it will be transformed [and lose out] tomorrow".

Although the strategy was initially greeted with doubts from some local officials and business executives, the relocation campaign has seen many outdated and polluting companies close and new industrial parks built to await "new birds".

However, after being battered by the global financial meltdown and the European debt crisis, Dongguan, which used to be one of the mainland's richest cities, is now teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.

The industrial parks built to accommodate hi-tech and innovative businesses remain half empty, and the city's economic output grew just 2.5 per cent in the first half of this year, the lowest growth rate in the province.

Wang's strategy came in for some serious questioning at the height of the global financial crisis, as many small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) closed and millions of migrant workers lost their jobs.

The ran an op-ed article in December 2008 criticising some unspecified local governments for "impatience in the process of emptying the cage to change birds", which "put great pressure on SMEs' survival prospects".

"The elimination of small- and medium-sized businesses is an oversimplified and crude way … the government should allow enough time for them to either relocate or upgrade," the article said.

After some economic commentators said Wang's tough stance on low-end manufacturers was strangling the vigour out of market forces, Wang softened his tone slightly in 2009, putting more emphasis on maintaining economic growth and job creation to avoid social unrest.

In 2010, Wang's strategy of moving older businesses was also questioned by Wu Jinglian, a well-known liberal economist on the mainland. Wu said it was not necessary to relocate such manufacturers, and asked "what if the new birds do not come?"

In a recent blog post, Wu wrote that some local cadres had misunderstood the true meaning of innovation and distorted the market by giving some sectors unmerited preference.

"In their minds, innovation only means hi-tech inventions or replacing the traditional manufacturing sector with emerging industries," he wrote, without singling out Wang. "And they forgot the true motive for innovation is to improve efficiency … the key to transforming the growth model."

He also said that special government endorsement of particular enterprises would harm the market by dealing a blow to other businesses.

"The role of government should be to establish a platform for all enterprises, giving them both pressure and momentum to innovate, and equipping them with necessary capacities to innovate … A wise government should know what it can do and what should be done by the market," he wrote.

Guangdong has now turned to massive infrastructure projects for the stimulus needed to spur economic growth amid stagnant trading conditions and consumer demand.

In May, the provincial government issued a notice urging the construction of 18 key projects - including railway lines, highways, urban light rail networks, massive oil refineries and the expansion of Guangzhou's main airport and - in response to a central government order to stabilise growth.

A picture showing Zhanjiang mayor Wang Zhongbing kissing an approval letter for a 70 billion yuan (HK$86 billion) steel project in May was widely mocked by internet users. But it was also a true reflection of that city's desperate need for big projects to boost growth, regardless of the fact that the mainland's steel production has exceeded demand since 2008 and that overcapacity is continuing to grow.

Wang's vision also saw the relocation of small factories and an end to the use of outdated technology as a way to tackle rampant pollution in a province known for its dirty textiles and electronic-waste recycling businesses.

But it seems that he overlooked the potential environmental impact of energy-intensive, polluting petrochemical plants along the coast, despite the poor environmental records of the country's big oil companies and protests by residents.

The has reported that the province is well on track to become "a world-level heavy industrial cluster" with four petrochemical bases - in Jieyang , Huizhou , Maoming and Zhanjiang.

Meanwhile, Wang has also made limited progress on another promise he made: to close a widening wealth gap. In a visit to Heyuan , one of the poorest cities in the province, in 2010, Wang vowed to narrow income disparity and eliminate poverty, and said it was a shame that a rich province such as Guangdong was still home to some of the country's poorest people.

The provincial statistics bureau says the income disparity index - the income level of the wealthiest 20 per cent divided by that of the poorest 20 per cent - narrowed from 6.08 a year ago to 5.33 in the first half of this year.