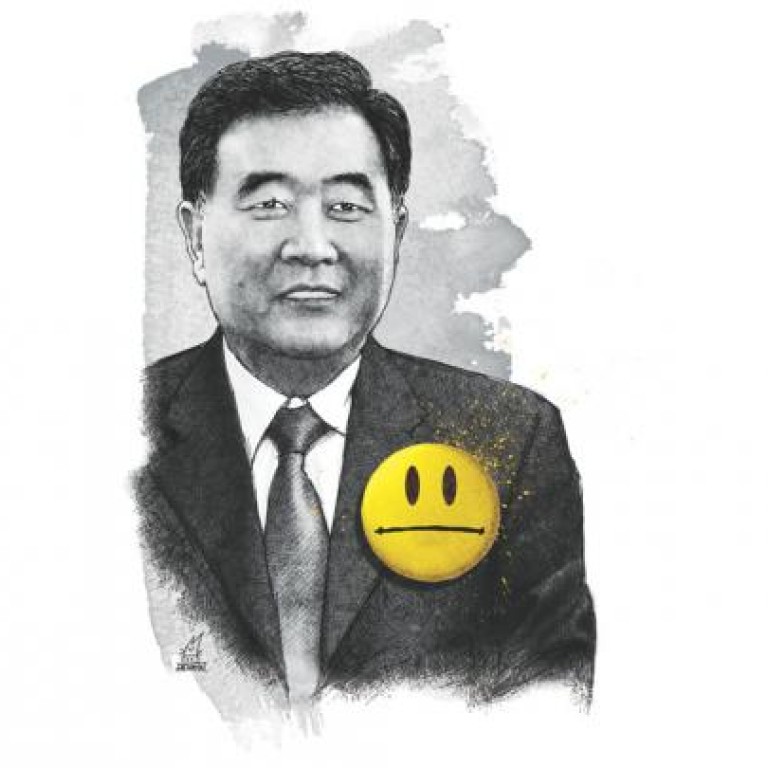

Guangdong's Wang Yang more style than substance, some say

Despite initial hype when Guangdong party secretary Wang Yang took office, he failed to deliver on his promises, some analysts say

While Wang Yang has certainly left his mark as Guangdong party secretary, it is safe to assume the province's citizens will not be looking back on his tenure with the same reverence as they did when Lin Ruo left office.

Everywhere, journalists, academics and common citizens paid tribute to the liberal party boss. In particular, they praised his support for greater press freedom and a stronger rule of law, a lasting legacy they continue to cherish this day.

For many in Guangdong, Lin's death just weeks before Wang's expected exit as party secretary served only to highlight the disappointment many have felt about his five-year tenure.

After taking office in 2007, Wang immediately caught the attention of reformers and foreign journalists for his promotion of more liberal policies and a seemingly softer leadership style.

He appeared to have the potential to leverage a reform message into political success, and some began discussing him as a candidate for the Politburo's Standing Committee after the party's 18th national congress.

But a consensus is beginning to take shape among political observers that Wang's tenure in Guangdong was probably more about advancing his career than about pushing for reform.

Analysts point to Wang's failure to build a base of civic organisations and his unwillingness to institute more effective anti-corruption mechanisms. They say reports of censorship in the run-up to the party congress have also weakened Guangdong's tradition of media freedom.

"He remains a good, consultative, Leninist, top-level cadre and there is no indication he will do anything that will undermine keeping the Chinese Communist Party in power," said Steve Tsang, a professor of contemporary Chinese studies at the University of Nottingham.

But many still say Wang did bring a more sensitive approach to his party secretary post, especially when compared with the hardline approaches of his predecessor, Zhang Dejiang .

For example, during last year's Wukan village uprising in which locals stormed a police station in an escalating dispute over government land grabs, rather than ordering police to forcefully crush the riot Wang released protest leaders, investigated land deals, jailed officials and oversaw elections to choose new leaders.

"Wang is less authoritarian, very different from the many mainstream party officials known for their autocratic rule and disregard for universal values," said Cheng Yizhong , the founder and former editor of and .

Wang's liberal approach in governing the province buoyed reformers' hopes.

In his first public speech, he placed heavy emphasis on President Hu Jintao's "thought liberation movement". Some form of the phrase, which has been interpreted as a licence for innovation by cadres, appeared 22 times in his address.

Wang's government initiated a corruption crackdown that netted thousands of wayward cadres, including former Guangdong political adviser Chen Shaoji . He also urged residents to discard the old notion that the party would provide for everything and to take more responsibility for their lives.

But, as the party secretary's tenure draws to a close, many say they have seen more style than substance.

"Wang became a more liberal politician as he matured in Guangdong over the years," said one Guangzhou-based political analyst who declined to be named. "But for Guangdong, he has delivered nothing concrete."

Wang's critics mock his "Happy Guangdong" movement, initiated last year, in which he pledged 423 billion yuan (HK$521 billion) for projects to increase the province's gross domestic product growth and improve people's livelihoods. He set up a "happiness index" to judge the movement's success.

But his critics have dismissed the initiative as "empty", pointing out that projects associated with the plan accounted for more than 60 per cent of provincial government spending last year.

Wang's record on civic organisations has also undercut his reformist image.

He had pledged to nurture the province's nascent non-governmental organisation sector and had vowed to streamline registration requirements and ease restrictions on fundraising and the hiring of foreigners. But in practice, labour rights advocates said Wang's policy has been used instead to target groups deemed disruptive.

At least seven Shenzhen-based NGOs have been shut down by Guangdong authorities in an unprecedented five-month crackdown, they said.

Perhaps most troubling to reform-minded observers was a recent crackdown on the press.

The province's relatively free media, in which newspapers often published criticism of local officials, remains a big legacy of Lin Ruo, who was previously a journalist.

But there have been reports in recent months of stories being spiked and journalists being pressured from above.

For example, the was reportedly forced to pull an in-depth report on the anti-Japanese protests in Guangzhou last month minutes before it went to press.

Cheng, 's founder, said: "Wang has always presented himself as a liberal … I don't understand how he could fail to maintain the outspoken tradition of Guangdong media."