Colloquial web jargon in People's Daily raises eyebrows

Use of web jargon in party mouthpiece commentaries raises eyebrows

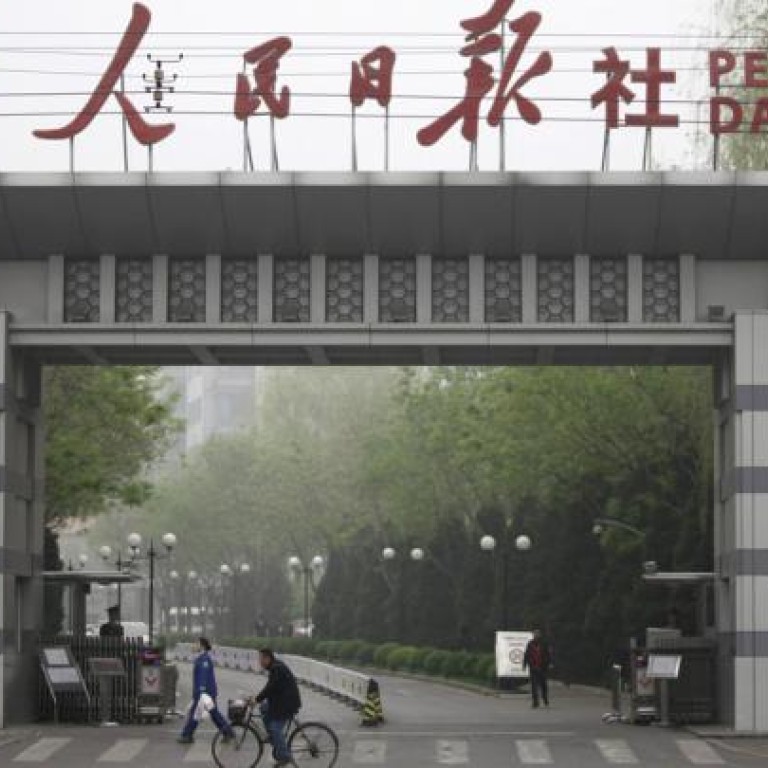

Communist Party mouthpiece raised eyebrows this month when it used web jargon in commentaries to reflect the challenging social problems facing China, ahead of the 18th party congress.

A November 3 piece about inspiring progress in China, which ran in a section about the congress, said that the relationship between the public and the government had reached a sensitive juncture, amid pressing social issues such as inequality, social unrest and even riots.

But some readers, particularly microbloggers, appeared to be less interested in the actual message being conveyed than they were in how it was being conveyed, as the column featured two colloquial Chinese phrases, and .

refers to young people who live privileged lives, particularly because of wealthy or well-connected fathers who are able to help advance their children's careers, regardless of their abilities. This phenomenon is widely blamed for worsening the social inequality problem.

In contrast, refers to young people on the opposite end of the social ladder. Most were born after the mid-1980s and have a very different outlook on life than their fathers' generation. They often use the word to describe themselves.

Song Shinan , an online commentator based in Chengdu , Sichuan , said mainly refers to the poor who have very few opportunities and chances to succeed in China, especially due to stiff competition.

"They aren't recognised by society, but they still want some degree of respect. They have the desire to succeed, but they don't have clear goals and are rather lazy," he wrote in a commentary that ran in last week.

The young generation, he said, has embraced the use of such phrases referring to one's status and mentality, and is often used to describe young migrant workers or junior staff members who are not satisfied with their lives, as well as recent university graduates who can't find work.

Seeing two colloquial phrases in the party mouthpiece was unusual. But then it happened again the next day.

On November 4, published a commentary featuring a pop culture reference that is especially popular among internet users. It translates to "Yuanfang, what do you think?" - a reference to a television drama called that takes place in the Tang dynasty (618-907). The show is based on the real life of Di Renjie , a judge who took it upon himself to investigate crimes. Legend has it that he solved cases involving 17,000 people within one year, and none of those convicted appealed the verdict.

In the show, Di often asks his captain of the guard, Li Yuanfang , what he thinks about the case they are trying to solve, and Li's response is usually along the lines of "I suspect that something fishy is going on".

The question is repeatedly asked in the drama, and the commentary noted that it is often asked by the public when calling into question the decisions and policies made by authorities.

The commentary went on to say that the central and regional governments should be more transparent and communicate better with the public, as people in the information age are eager to express their opinions on everything from the distribution of wealth to the location of factories that threaten to pollute their hometowns.

Although some online commentators have praised the use of these types of "web phrases" in state mouthpieces, believing it can help narrow the gap between propaganda authorities' generally bureaucratic tone and the country's vast number of internet users, former editor Li Datong said it doesn't necessarily mean the Communist Party mouthpiece is becoming more liberal.

"You can't call it a change by simply using several new web phrases [in commentaries]," he said. "The doesn't have the decision-making rights to reform itself, unless the Communist Party abandons its propaganda policies.

"For example, when Mo Yan became the first Chinese national to win the Nobel Prize for Literature last month, the and many other urban dailies made it the lead story with huge photos, but it was only a 200-word brief on an inner page of the ."