In China, losing battle against lung disease and workers' rights

A migrant worker shocked China in 2009, when he volunteered for an operation to open up his chest to prove he was suffering from a fatal lung disease. The case has highlighted the challenges workers face as they seek compensation for occupational illness on the mainland.

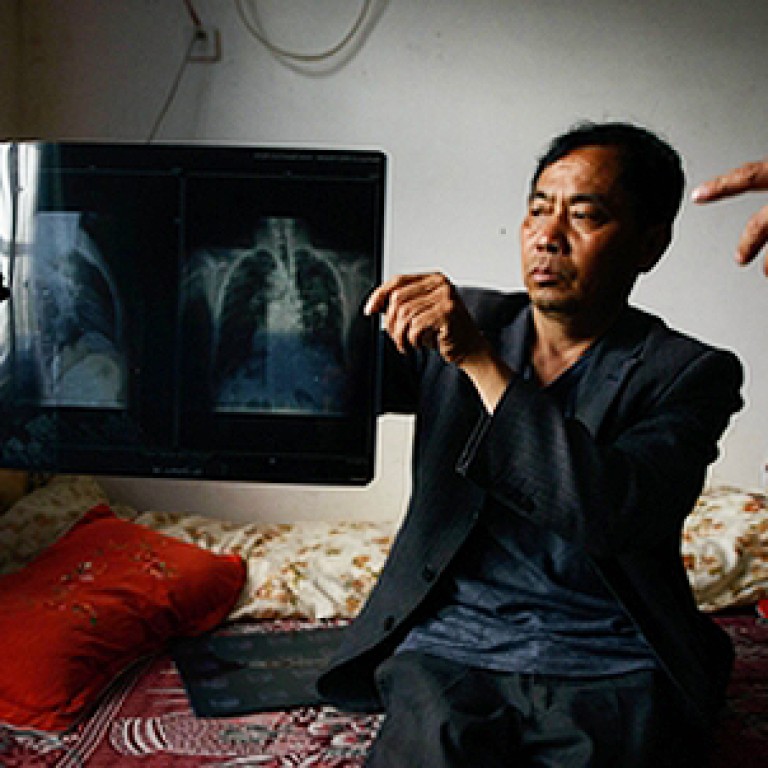

Migrant worker Zhang Haichao wakes up three or four times a night.

“I have to lie flat on the bed and can’t turn over. I must get up and sit for a while after sleeping for a long time, otherwise I can’t breathe,” he said. Every day it gets harder for him to breathe as his pneumoconiosis recurs. A lung transplant is his only chance of surviving.

Zhang shocked China in 2009, when he volunteered for an operation to open up his chest to prove he was suffering from the fatal lung disease, which he contended was developed on the job. The case has highlighted the challenges workers face as they seek compensation for occupational illness on the mainland.

The incurable disease is caused by long-term exposure to industrial dust, such as from coal mining. It is the most serious and most common occupational disease in China today, according to official figures. Most sufferers are rural migrant workers.

Zhang is one of about six million pneumoconiosis victims on the mainland, an estimate from the Love Save Pneumoconiosis Foundation that is nine times more than official figures released by the health ministry.

The mainland recorded 676,541 cases of pneumoconiosis in 2010, which accounted for 90.21 per cent of all occupational cases that year, said the Ministry of Health.

“The Ministry of Health figures count only patients who sought formal diagnosis of occupational injury from the centres for disease control,” said Wang Keqin, a former investigative journalist who founded Love Save in 2011. “Ninety per cent of pneumoconiosis patients are migrant workers, but fewer than 10 in every 100 workers are qualified for the diagnosis.”

Whenever I cough, feel suppression in the chest, forcibly breathe, do sport or talk for a long time, my lung aches

Two officials from local disease control centres confirmed to the South China Morning Post that the official figure does not reflect the real number of patients. Peng Haibo, director of the Disease Control Centre in Loudi city, Hunan province, estimated that the true figure in Loudi is about five times what his centre has recorded. He said the situation in other parts of China was similar.

Both authorities and non-government organisations said it was impossible to know how many people suffer from the disease without a nationwide test, that Peng said would be costly.

Wang said the government was trying to hide the truth by not conducting the test. “The actual number could be astonishing,” he said.

Still, critics have called the government indifferent to migrant workers with pneumoconiosis.

Duan Yi, head of China’s first law firm dedicated to protecting migrant workers’ rights, said government inaction had undermined society’s respect for labourers.

Zhang said he thought it was unfair.

“Most people with pneumoconiosis harbour hatred towards the society,” he said via his Sina Weibo microblog. “A worker is left forsaken when he has sacrificed his health and even his life for the construction of the country.”

Like Zhang, most rural migrant workers afflicted with the disease are not qualified for a formal occupational diagnosis, which is required for compensation under Chinese law.

If a worker wanted to be evaluated for occupational injury, the person must have a labour contract. But only 5 per cent of rural migrant workers have such contracts with their employers, said a Chinese Academy of Social Sciences survey in 2008.

Dai Chun, from Love Save Pneumoconiosis, said the lack of labour contracts was the main reason workers fail to receive compensation. The lag time from when a patient gets pneumoconiosis to when symptoms show, which varies from three to 30 years, is also another reason for lost causes.

Dai Chun also points out that Chinese law requires “employers to present materials regarding occupational hygiene and health surveillance” for the diagnosis and verification of worker illness. Most employers are not willing to present such materials, fearing doing so would harm business.

Under the law, the cost of treatment also falls on employers.

Love Save Pneumoconiosis said it had more than 8.4 million yuan for pneumoconiosis sufferers and helped fund treatment for 672 people as of June 7.

But the foundation said the relief funds were a drop in the bucket, amounting to less than 2 yuan for each of the six million patients.

Earlier this year, Zhang suffered from another bout of pneumoconiosis.

“I arrived at home on February 6 for Lunar New Year. The constant work stress plus cold weather in northern China caused the recurrence. I was diagnosed with pneumothorax [lung collapse] and was sent to hospital,” he said.

The chilly weather in Zhang’s hometown in northern China has continued to threaten his life. The compensation he got from the government in 2009 is running out. For convenience, he’s renting a small house near the hospital, waiting for a lung transplant.

He believes overwork may be the trigger.

“Whenever I cough, feel suppression in the chest, forcibly breathe, do sport or talk for a long time, my lung aches,” he said.

He appeared calm about his situation, even as he enters the last days of his life. “It’s incurable,” Zhang simply said.

Patients of pneumoconiosis die at an average age of 35 to 40 years old.

Zhang said he was not worried about himself. He was concerned that after his death, his young daughter would be left alone without anyone to care for her.

Zhang and his wife divorced last summer, and he got the custody of his daughter, 7. The divorce rate among pneumoconiosis patients is much higher than average people, according to media reports. The disease also drives millions of families into poverty because the cost of treatment is an almost bottomless pit.

Zhang said he was eager to live, not just for himself.

“I will contact reporters and continually speak out for pneumoconiosis victims as soon as I feel better,” he said.